Writer Adina Horwich only met Yehuda Miklaf and his wife Maurene in Jerusalem, even though both Adina and Yehuda are from Nova Scotia. (photo by Adina Horwich)

So, this guy walks into my Yiddish group one fine Sunday in Jerusalem – this is not the beginning of a joke. In the group, we welcome anyone who is into Yiddish, with any background, and, on that day, Yehuda was introduced to us. We went around the room asking him questions. I asked where he hailed from. Little could I have anticipated his answer: Nova Scotia.

“I don’t believe it!” I said. “So do I!” Then, “From where, exactly?”

“Annapolis Valley.”

“Oh,” I paused, thinking to myself, I’d be hard-pressed to find any Jews there.

Later, Yehuda’s story was revealed when the teacher matched us up to work together.

Yehuda, an Esperanto speaker and aficionado, has only recently started to learn Yiddish, while I have been at it for 15 years. I started off with little but the smattering I heard as a child. Yehuda happened upon it by the by, via a friend in the hand-printing scene, where he is an active, prominent member. With the characteristic zeal that he tackles so many projects, and lots of gumption, he has taken to Yiddish very well.

The sight and sound of us two old-time Bluenosers (nickname for Nova Scotians) hacking a chainik in Yiddish, is too precious. But, most of all, I like when Yehuda slips into the down-home accent I grew up with. That is when I really kvell.

Né Seamas Brian McClafferty, Yehuda was born in the mid-1940s to a father with Irish roots and a mother with origins in Quebec. The youngest of eight, he had an idyllic childhood, as a small-town Catholic youngster in Annapolis Royal, which today has a population of only 530.

In his last year of high school, Yehuda attended a Fransciscan seminary in upstate New York, his first foray away from home. With his fellow students, he passed a building with Hebrew letters, which intrigued him. A friend he asked about these unfamiliar markings promptly replied: “That’s just Hebrew.” Yehuda had never seen, much less met, any Jews.

He completed his last year of high school and then spent a year of silence and meditation at the novitiate in the Adirondacks. The following year, he furthered his studies towards the priesthood, commencing a rigorous and intense program that sounds like a yeshiva govoha (Torah academy of higher learning).

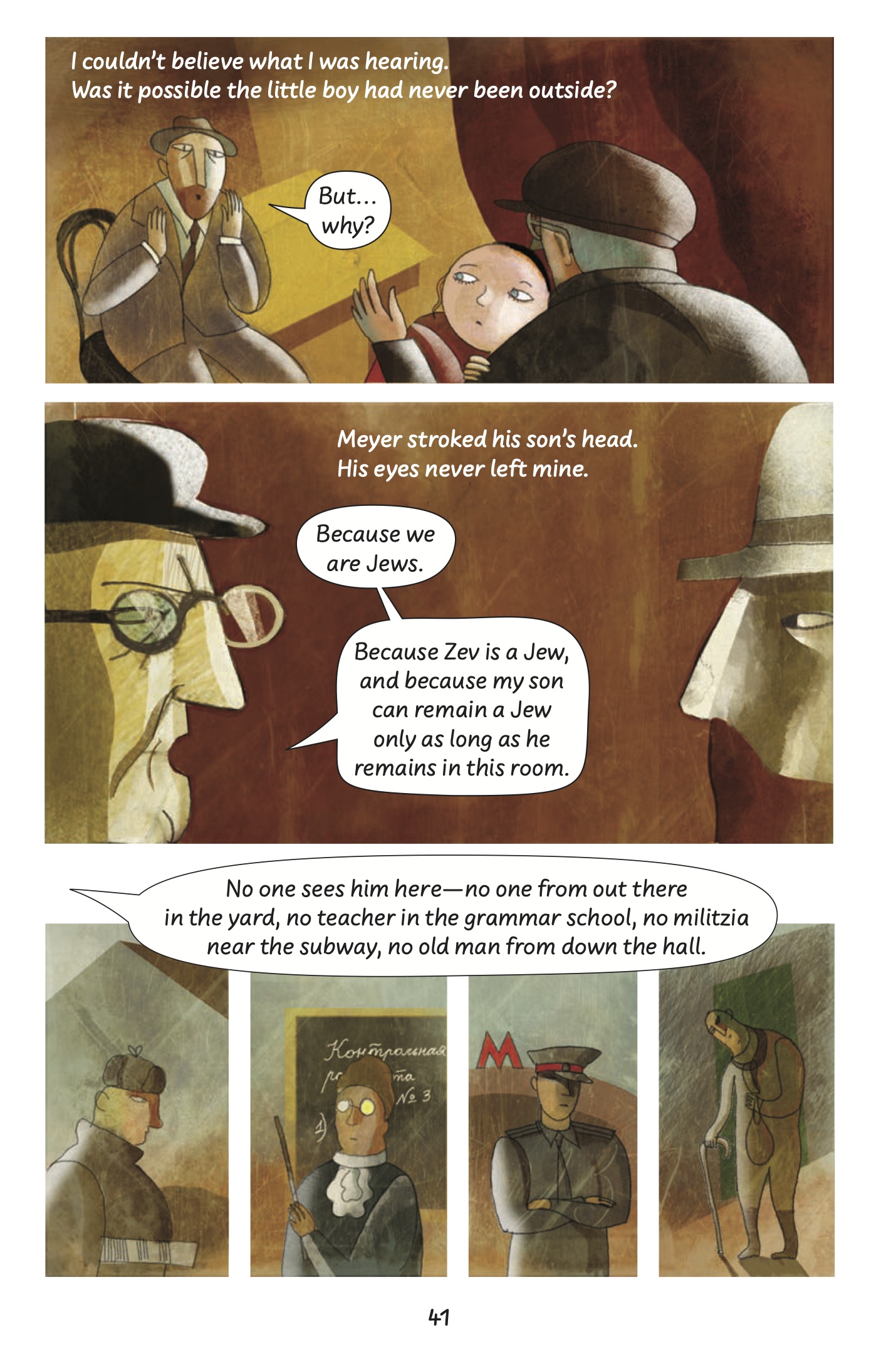

Discipline and training, mostly in silence, hours of meditation and living under austere conditions, Yehuda carried on through to the second of four years. He heard a lecture about the Torah, which was demonstrated by a small model scroll, and delved deeply from then on, backed by the church’s ecumenical approach of spirituality and faith. He availed himself of the library to his heart’s content and took to reading the Hebrew Bible over and over again. He didn’t know it at the time, but his first steps towards life as an Orthodox Jew were taken, while he was encouraged to become a scholar of the “Old Testament.”

Over the four years of study, Yehuda began to have rather different ideas about how he wanted to live his life.

Returning to Canada in the mid-1960s, he spent time in Toronto and in Nova Scotia, taking road trips home to tend to his father who had taken ill. Things grew clearer.

Yehuda absorbed every mention of things Jewish. It was an emotional attachment. In 1966, after having left Christianity, he discussed his evolving beliefs with a Jewish friend, who said: “You sound more Jewish than me. I’m surprised that you haven’t converted.”

The conversion process was long but not arduous. Yehuda took a class in Toronto and eventually went to the mikvah.

He and his wife Maurene – who he met through his roommate in Toronto – visited Israel, as tourists, for an extended vacation. They had not intended to make aliyah, but, smitten with Israel, as so many of us are, did so three years later.

After making aliyah, Yehuda had to “rinse and repeat,” so to speak, as often happens with conversion. Israeli rabbinic courts do not automatically accept even the most stringent diaspora Orthodox ones, and Yehuda had to go through it again, studying for a year and then going to the mikvah. The converting rabbi gave him the option of choosing a name and Yehuda suited him, since that’s where the word Jew comes from. Miklaf (literally, “from parchment”) was a good abbreviation of McClafferty, he thought, and could not have been more fitting for his chosen profession of printer and bookbinder.

Like most new immigrants at the time, they started out at an absorption centre and had a routine klita (absorption/integration), including Hebrew language studies at ulpan. Maurene got a job in high-tech and Yehuda opened a studio. He started out by binding the original of David Moss’s My Haggadah: The Book of Freedom, and branched out into printing.

The couple attends an Ashkenazi shul but try not to be pigeonholed as being from one background (Sephardi or Ashkenazi). Early on, Yehuda tasted some traditional Ashkenazi delicacies and learned how to make potato kugel, for which he’s now famous, along with kneidlach.

Yehuda still has two siblings in Nova Scotia and visits his longtime friends in Annapolis Royal.

Our paths from the Atlantic led us to meet in Jerusalem, where we raised our families. The Miklafs have two children and several grandkids. Their daughter was a high school friend of my daughter’s, and both women have been living in the same community, and they see each other now and again.

Ma’aseh avot siman l’banim – the deeds of the fathers are a sign for the children – or, in this case, Ma’aseh horim siman l’banot, the deeds of the parents are a sign for the daughters.

Adina Horwich was born in Israel to Canadian parents. In 1960, the family returned to Canada, first living in Halifax, then in a Montreal suburb. In 1975, at age 17, Horwich made aliyah, and has lived mostly in the Jerusalem area. She won a Rockower Award for journalistic excellence in covering Zionism, aliyah and Israel for her article “Immigration challenges.”