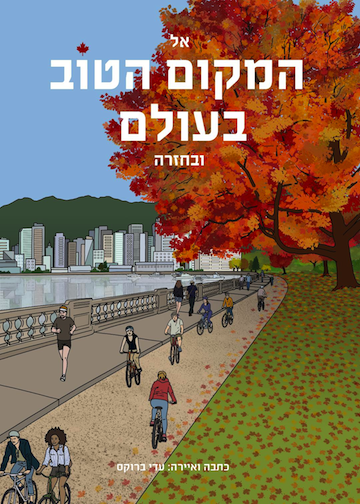

Adi Barokas and her husband Barak during their time in Vancouver. (photo from Adi Barokas)

I read a review in an Israeli newspaper of Adi Barokas’ Hebrew-language graphic novel, the title of which translates as The Journey to the Best Place on Earth (and Back). I also read a scathing review of that review on the JI website, written by Roni Rachmani, an Israeli who lives in Vancouver. Disturbed by several aspects of the criticism, I decided to look into the book – and its author and illustrator – myself.

When I made aliyah from Canada in 1975, I had many difficulties acclimatizing to Israel. In reading Adi’s book, it was as though she had written the book I’d always wanted to write about Israel. Her experiences in Canada, which took place three decades after mine in Israel, were decidedly similar.

Aliyah is often thought of as a lofty, spiritual ascent, but, in a practical sense, it is effectively like immigrating to any other country. In the euphoria and joy of making the huge leap, this can be overlooked.

Decades before the internet, cellphones, Skype and WhatsApp, I left my home and family, strongly motivated by Zionist ideals, conveyed to me by my parents’ Israel experience of the 1950s. I longed to live a fuller Jewish life and take part in the developing history of Am Yisrael. Wrapped in a fuzzy cloak of enthusiasm, naïve and wholly unfamiliar with Israeli society, things turned out to be very different than the utopian image I’d envisioned. However, nearly half a century later, I am still grateful to be here.

Adi and her husband Barak met in the mid-2000s. Shortly after they married, Barak was called up to serve in the Second Lebanon War. They wanted to live in a quiet, peaceful society where they could just pursue their lives and careers, so they headed to Vancouver, which is often billed as one of the best places in the world to live. Unfortunately, they met with many unexpected challenges, mostly related to cultural differences. They tried to feel like they belonged, but never overcame feeling like foreigners.

For me, the in-your-face abrasiveness for which Israelis are known was an enormous shock to my more reserved, polite system. In Vancouver, Adi found those Canadian-associated traits off-putting and two-faced.

Adi and Barak were seeking a breather, serenity and space from the intense pace of life in densely populated Israel. With excessively high expectations that everything would be just so, they came to Vancouver. But for them, too, the culture shock was huge. They were not accustomed to so many rigid rules and regulations.

Adi had never lived in such a diverse society and was excited to interact with people of many ethnicities from around the world. It took a long time to catch on to the nuances, the nonverbal cues, of how people in Vancouver socialize – what topics are off limits, for example. Coming from Israel, a very liberal place, where most people freely express their unsolicited opinions, this was challenging.

Adi and Barak found it odd that everything was so quiet and calm in Vancouver. They were used to a lively, noisy society where people mix in close proximity. In Vancouver, everywhere they went, voices were barely audible and, so, they gradually adjusted and lowered their own tone of voice, and limited their conversations to certain topics.

The couple were eager to socialize, especially with their fellow foreign colleagues, with whom they felt more affinity than with Canadians. They initiated get-togethers, extended invitations, but they found everything so formal and stilted and rarely reciprocated. The only safe subjects of conversation were about hockey or the weather, nothing the couple felt was deep or of substance. This hampered their forming close friendships. Their sense of strangeness, that they would never fit in, grew.

On the flipside, schooled in the notion of appropriate table talk in Canada, I would often feel embarrassed at subjects discussed so frankly in Israel. It felt like an infringement on private matters, mostly with regards to money and personal relationships.

In Israel, people stand far less on ceremony, tell others to drop by any time, and mean it. But, to me, these invitations seemed an empty manner of speech. In Hebrew, the word for “to drop by” (tikfetzi) and a less polite version of “buzz off” (tikfetzi li) are the same!

I was baffled when people would ask why I’d come to Israel. It’s obvious to anyone imbued with Zionist and Jewish values that aliyah is a natural step, that Israel is the place to build a future. But, instead of words of praise or encouragement, Israeli peers, if they showed any interest at all, found it amusing that anyone would leave what they assumed was the easy life, to come to what was a troubled society. There was certainly no welcome wagon, no grace period to acclimatize. There were few invitations for holidays or Shabbat. The workplace, where I was often the only non-Israeli, was an even rougher scene – I wasn’t aware of how critical having connections really is, of how offices and organizations operated.

Across the ocean, Adi and Barak arrived with several science degrees under their belts, and had to swim the stormy seas of academic life in a B.C. university. There was some discrepancy between how they saw themselves – as conveying constructive criticism – and what some of their colleagues and acquaintances shared with them. This created awkward misunderstandings, a lack of candid communication and obstacles to their ability to settle in.

The couple had to wade through seemingly endless red tape through bureaucracy channels. They found it infuriating to jump hoops with indifferent, intransigent civil servants, who never saw them as individuals.

I can completely relate, as I have had to navigate mountains of paperwork, all in Hebrew, which, when I first arrived, was at an afternoon Hebrew school level. English was not widely spoken, and clerks lacked any service orientation – there was scarcely any eye contact. I miss even a perfunctory exchange of pleasantries, which, in Israel, is considered a waste of words. But Israel has come a long way and there is a marked improvement; as well, much can be done online. That’s not to say everyone is pleasant, but at least civil.

Barak and Adi became increasingly frustrated in Vancouver and it began to affect their mental and physical health. They became discouraged, falling into despondency, and their lives were out of their control. Under steadily increased pressure, their goals seemed to be slipping from their grasp, yet they were obligated to stick it out. They would have loved to have returned to Israel much sooner, but honoured their academic commitments, which were critical to enabling Barak to advance in his career in cancer research. Competition is fierce in academia but, eventually, Barak was offered a position at Ben-Gurion University, for which they are grateful.

Adi asked me why I stay in Israel. The answer is that, despite not knowing the ropes initially, having had to master Hebrew and the Middle Eastern mentality, the reasons for coming remain steadfast: unwavering belief in Zionist ideology and the privilege of fulfilling the mitzvah of settling in Eretz Yisrael. Still reserved and well-mannered at my core, I can and will tell someone off in Hebrew if they cut in front of me in line. And driving has forced me to become assertive.

Life in Israel has made me resilient, not automatically accepting of everything that’s dished out, and no longer complacent. My children and grandchildren have none of my social concerns and are rarely bothered by the things that irk me. They do recognize and understand that it hasn’t been a walk in the park for me. They greatly benefit from knowing English, which I spoke at home to my kids and which I also speak with my grandchildren.

Distance has impacted relationships with my relatives, who are all in Canada, and I miss them. But, in Canada, families commonly live far apart and visit only a few times a year. That’s just the norm and how I grew up, too. In Israel, we belong to a close-knit clan, with whom we celebrate holidays and other occasions; regularly helping one another is everything here.

Living in Vancouver, Adi was frustrated by the positive-thinking approach that was all the rage, but didn’t work for her. She needed to be able to share her concerns openly. She wanted practical advice, instead of being brushed off all the time, with people either trying to divert her attention or change the subject. At least the experience forced her to become more self-reliant.

Adi began to delve into other areas beyond academia, having been turned off the sciences for good. She tapped into her creative side, got her driver’s licence, went swimming, started writing. Both she and Barak took up yoga and meditation.

Adi sought therapy and finally found a therapist who was helpful, which contributed to Adi’s bouncing back from within. Time spent in nature, and developing her writing and artistic skills, offered solace.

It was during this process of self-discovery and self-care that the couple decided to start a family, and they had a son.

When an offer came for Barak to take up a post in Leicester, England, it meant once again picking up and leaving, and having to learn their way around a new place. But, it appealed to them, as Leicester was off the beaten track and the small city ambience appealed to them. As well, the move brought them closer to home. Instead of the 10-hour time difference, they were only two hours behind Israel time-wise and a five-hour flight away.

Outside Israel, Jews tend to belong to communities where they gather to share religious and cultural activities and strengthen their bond with Israel. For me, coming to Israel to live in a predominantly Jewish society was enlightening, yet it wasn’t easy to understand the many different customs. I enjoy the Jewish character and vibe of Israel in many facets of the public sphere. Life revolves largely around the Jewish calendar, especially the celebration of Shabbat and festivals. What binds us is our unique, incredible history and heritage.

Had I been better prepared, come with more defined goals, and more socialized in a Jewish environment, I might have fared better. Even when the going was rough, returning was never an option, however. I am living a meaningful life in Israel, where I have mostly resided in the Jerusalem area.

We have all witnessed Israel evolve into a modern, advanced country, making huge strides in every realm imaginable. On occasional visits to Canada, I enjoy the familiar scenery, the cold, the language and pleasantries, though a noticeably different mindset from the locals is apparent.

Immigration is a tremendous and profoundly complex undertaking. It entails much uncertainty and many twists and turns. No matter how much any immigrant plans, one never knows how things will unfold. It is an arduous process that demands full commitment with every fibre of one’s mind, body and soul. Fellow ex-pats can only offer so much support and help. The individual immigrating has to go through the process on their own terms.

Adi and Barak have since returned to Israel. Over a total of eight years away, they learned a great deal about themselves, individually and as a couple. Growing up in Israel, they naturally identified as Israelis, their Jewish identity cultural. While abroad, they realized that they were viewed by others not only as Israelis, but as Jewish, as a minority. This heightened their awareness, added a new dimension.

Time away has changed them, considerably, and they returned to a somewhat changed Israel. They have settled on a kibbutz 20 minutes from Be’er Sheva, where they and their now two children enjoy spectacular scenery in the Negev, a warm climate and a caring community. They have found their home right here, at home.

Adina Horwich was born in Israel to Canadian parents. In 1960, the family returned to Canada, first living in Halifax, then in a Montreal suburb. In 1975, at age 17, Horwich made aliyah, and has lived mostly in the Jerusalem area.