It’s almost a new year. We’ve been taking stock more than usual throughout the month of Elul. It’s a valuable skill – being able to do regular cheshbon hanefesh, accounting of the soul, reflecting on our views and actions, with an eye to self-improvement, maybe even creating a positive ripple effect that extends beyond ourselves.

Two new children’s picture books introduce – or reinforce – the Jewish values of Shabbat (taking a break from work and technology, thereby recharging our physical and mental selves) and tikkun olam (taking care of ourselves, our homes, our neighbourhoods, and so on). They remind us that making the world better starts with us, what we do, how we treat ourselves and others.

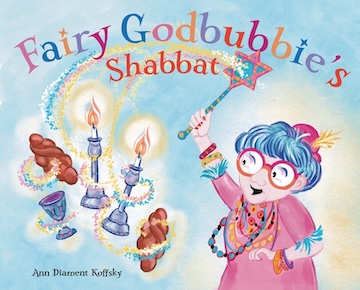

Seattle publisher Intergalactic Afikoman released Fairy GodBubbie’s Shabbat by Ann Diament Koffsky this month. Koffsky has written and illustrated more than 50 kids books, with many about Judaism, its holidays, foods and symbols. Her website is worth checking out: there are reading guides, you can see her many artistic styles, download colouring pages featuring scenes from her books, as well as other images, and, of course, there are links to purchase her books.

In Fairy GodBubbie’s Shabbat, the Mazel family is busy and seems happy enough, Dad on his laptop, Mom on her phone, Sara playing games on a tablet. But, “Why is no one schmoozing?” wonders Fairy GodBubbie. “Noshing?? Kibbitzing!”

“Unlike regular fairy godmothers who come only when called, Fairy GodBubbies just show up to fix things.

“Even when they’re not invited,” writes Koffsky.

So, poof! With a couple of Shabbat candles and a frequency jammer, Fairy GodBubbie helps the Mazels experience a different kind of Shabbat, a much more fulfilling one, a magical one. And readers can create the experience at their own homes, trying out what Koffsky calls a “a Tech Shabbat – a day away from screens.” She asks, “If your family does choose to try out a Tech Shabbat, what would you most like to do during that time?” And offers some choices – “Will you eat a family meal? … Curl up with a good book?” – and encourages readers to come up with their own ideas to make their “next Shabbat feel magical.”

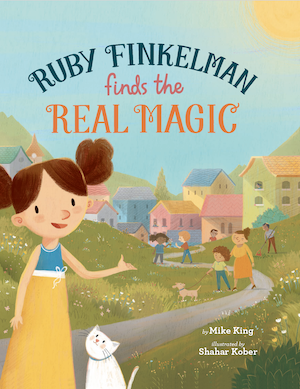

The Collective Book Studio’s Ruby Finkelman Finds the Real Magic, written by Mike King with illustrations by Shahar Kober, which came out earlier this year, also features a young heroine and, as the title indicates, “magic.” But there are no magical GodBubbies; rather, a self-realization that a beautiful village, a beautiful life, don’t just happen by magic – happiness, cleanliness, kindness, etc., require not only effort, but sometimes doing things you don’t enjoy doing. In Ruby’s case, she “especially didn’t like brushing her teeth,” so, one night, she decides, “I’m never going to brush my teeth again.”

The Collective Book Studio’s Ruby Finkelman Finds the Real Magic, written by Mike King with illustrations by Shahar Kober, which came out earlier this year, also features a young heroine and, as the title indicates, “magic.” But there are no magical GodBubbies; rather, a self-realization that a beautiful village, a beautiful life, don’t just happen by magic – happiness, cleanliness, kindness, etc., require not only effort, but sometimes doing things you don’t enjoy doing. In Ruby’s case, she “especially didn’t like brushing her teeth,” so, one night, she decides, “I’m never going to brush my teeth again.”

Even such seemingly inconsequential actions have repercussions. Other kids stop brushing their teeth. Then they decide not to wash their faces, tidy up after themselves or treat one another kindly. Parents nag, children kvetch. The grownups become so exhausted, they have “no strength left to lift a toothbrush, do the laundry, take out the garbage, and on and on.” Kvellville soon turns into what neighbouring villages start calling “Schmutzville.” A town meeting devolves into several arguments, everyone turning on one another.

Seeing the madness, and realizing how it all started, Ruby sets about to right the situation.

“Mensch is a Yiddish word that means ‘human,’ but when used in the sense of ‘being a mensch,’ it means being a human in the best possible way, or being the best human that you can be,” writes King in an author’s note at the end of the story. “But it’s not only a Jewish thing – it’s a universal value, an idea of how to act in a way that makes the world a better place, simply because you behave in a good and kind way.”

While the toothbrushing premise is a little bit of a stretch, King is a pediatric dentist, so it’s no wonder, and he does manage to make the story work. It’s a wonderful message, of course, and Kober’s artwork is delightful.