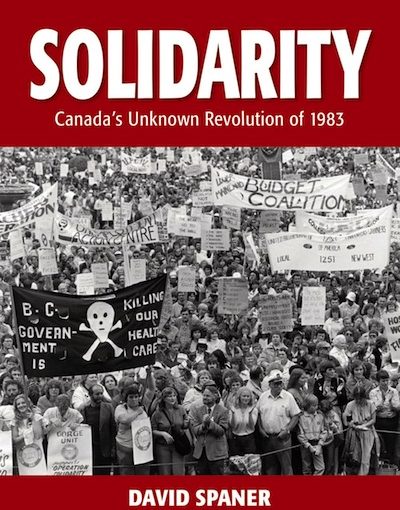

David Spaner’s new book, Solidarity: Canada’s Unknown Revolution of 1983, forms an archival testament of one of this province’s most dramatic epochs.

One of the funny things about watching the 1976 movie All the President’s Men, about how Washington Postreporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein broke Watergate and brought down Richard Nixon, is that, after 138 minutes of sitting on the edge of your seat, you realize that you’ve watched nothing more than two men making phone calls and knocking on doors asking questions. In other words, stuff doesn’t need to blow up in order to make an excellent movie. This thought occurs when reading Vancouver author David Spaner’s new book, Solidarity: Canada’s Unknown Revolution of 1983. On the surface, the book is a litany of bureaucratic meetings and activists’ backstories. Together, they form an archival testament of one of this province’s most dramatic epochs.

Spaner, an activist and journalist who has been immersed in the left-wing ferment for most of his life, chooses a different Hollywood reference. At the end of the book, he alludes to the 1983 film The Big Chill, in which disenchanted middle-agers convene for a friend’s funeral and lament their glory days. For anyone who has been part of British Columbia’s left-wing movements – recently, in 1983, or decades earlier – this book will provide many Big Chill moments. An initial criticism might be the title, which alleges this history is forgotten. Any person who was living in British Columbia in 1983 and even moderately politically aware will not forget that riotous time, though Spaner revives it effectively for new audiences.

Spaner’s thesis is that British Columbia’s well-known legacy of progressive activism that began in the 19th century converged in 1983. All the economic, social, racial, gender and other movements cohered in response to unparalleled government excess – and then refracted again into the myriad organizations and causes that drive B.C. politics today.

The province’s long history of progressive activism weaves its way through the book. More volunteers from Vancouver signed up to fight Franco’s fascists in the Spanish Civil War than from any other North American city save New York, Spaner says. And, in a more trivial note, he claims that the Industrial Workers of the World got their nickname “Wobblies” right here. Greenpeace was founded in Kitsilano in 1971. Movements against the Vietnam War and nuclear warships found fertile ground here. A squatters’ park stopped development at the entrance to Stanley Park. A “smoke-in” in Gastown protested police brutality and called for loosened marijuana laws. The Simon Fraser University Women’s Caucus, formed in 1968, was, according to the book, not only the first such group in Western Canada, but the first in North America. The first rumblings of gay rights activists were heard in these parts around the same time.

With all this as a foundation, the events of 1983 exploded out of the results of the provincial election on May 5. Dave Barrett’s New Democrats, who had governed the province for a short but tumultuous two-and-a-half years beginning in 1972, had been widely anticipated to defeat Bill Bennett’s right-wing Social Credit government. Instead, Bennett pulled out a surprise victory – and then launched a “restraint movement” that was unprecedented in Canada and is often compared with Thatcherism in Britain and Reaganism in the United States. On July 7, Bennett and his cabinet “unleashed a far-right legislative avalanche that tossed asunder virtually every advance achieved by B.C.’s social activists and trade unionists,” Spaner writes. “In an instant, and from every corner of the province, there was a rising of resistance.”

Almost exactly two months after the election, Bennett’s Socreds dropped 27 radical bills, affecting every area of government operations. For starters, 1,400 members of the B.C. Government and Services Employees Union (BCGEU) were summarily fired the day after the bills were tabled. The government eliminated special education programs, reduced student loans, fired family support workers, took away autonomy from local school boards and mandated fewer teachers and larger class sizes. Environmental protections were removed, welfare rates frozen, healthcare facilities closed and programs, including the Human Rights Commission, were cut. Funding for programs in services like the Vancouver Women’s Health Collective were eliminated. They closed the Tranquille mental health facility in Kamloops and fired its 600 employees. Labour relations laws were amended to take away rights such as seniority, working hours and overtime in collective agreements. Tenants could be evicted without cause and the Rentalsman’s office was eliminated, meaning any disputes would have to go to expensive court proceedings. The Agricultural Land Act, intended by the Barrett government to protect farmland, was gutted. User fees for hospital care increased exponentially.

Organized labour mobilized as soon as they could shake off the disbelief about what they were confronted with. They formed Operation Solidarity, an umbrella covering 400,000 unionized workers in the province, under the not-so-gentle guiding hand of the B.C. Federation of Labour. A parallel group, the Solidarity Coalition, was a motley amalgam of community groups and activists, less hierarchical and disciplined than the trade union groups. (The names were lifted from the nascent Polish anti-communist movement emerging at the time, but the ruptures in the B.C. movement make the moniker somewhat ironic.)

The first big rally took place in Victoria’s Memorial Arena, attracting 6,000 protesters. This was where the initial idea of an all-out general strike gained currency – and the seeds of the movement’s destruction were planted. A massive rally followed in front of the old CN station at Thornton Park on Main Street in Vancouver, on July 23. Organizers had hoped for 2,000 attendees but 25,000 showed up.

As is common in activist circles, Jewish individuals played an outsized role. The author, who is Jewish, comes by his credentials naturally – his grand-uncle was a good pal of Dave Barrett’s dad, Sam, in East Vancouver. One of the most visible faces of the movement was Renata Shearer, a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany who was fired as the province’s human rights commissioner. Feminist and union leader Marion Pollock and Carol Pastinsky, who grew up in a left-wing household that hosted meetings of the United Jewish People’s Order, are featured in the book. And, of course, Barrett, who, despite his recent defeat, led the charge in the legislature against the onslaught, was the province’s first, and so far only, Jewish premier.

Another Jewish person, Stan Persky, launched and edited the movement’s publication, Solidarity Times. The newspaper, funded by organized labour, provides one of many examples in the book about bitter feuds within and between the disparate factions in the Solidarity mishpachah (family). A bunch of young, idealistic journalists who were working under Persky got a taste of censorship that they might have expected in a career with the bourgeois press but perhaps had not anticipated from their comrades in the movement. “Remember who writes your checks,” a union apparatchik warned them after spiking a story that didn’t toe the union line.

One of the most visible schisms in the mass movement occurred at a huge rally where most of the rank-and-file attendees were apparently champing at the bit for a general strike, but the more cautious leader of the movement, Art Kube, instead urged everybody to get a copy of a petition, have their neighbours sign it and send it in to the government in Victoria.

Said one activist reflecting his response that day: “We want militant action. We want to shut down this province. Instead, were being told, ‘Go get a petition signed.’”

But, while Kube was the one who disappointed that day, many in the movement believe it was his illness – a physical or mental breakdown – that led to what many or most view as the ultimate betrayal of the entire project. The BCGEU and the teachers’ union went on strike, shutting down huge swaths of the province. As pressure built, an unexpected – and largely unwanted – resolution was hatched by one segment of the union movement.

Within the Solidarity movement, there were schisms between the far-left and the comparatively more right-leaning unions, between radicals who wanted transformative change and reformers more narrowly opposed to specific legislation. There were, of course, also a lot of very strong personalities, all packed together and stressed by the pressures of the time.

With Kube sidelined by illness, the B.C. Federation of Labour sent Jack Munro, one of British Columbia’s feistiest, foul-mouthed and most divisive union figures, to meet with Premier Bennett at his home in Kelowna. When other partners in the Solidarity movement found out that the meeting was taking place, they knew they were done for.

“Munro and Bennett reached the quick agreement, settling the BCGEU contract but offering little else to most Solidarity members,” writes Spaner. “Then they stepped out on the premier’s patio to announce their Kelowna Accord.”

“We were all in tears,” recalls one activist. “It was a horrible betrayal.”

Once a big swath of the union movement had pocketed what they wanted from the government, the larger movement effectively fizzled out.

“Some longtime union activists simply don’t have a bigger dream, so it was impossible for them to see the Solidarity drama as a failure. To them, it was just another contract negotiation,” Spaner writes.

But while the movement itself may be gone, the legacy lives on, Spaner argues. Those trenches formed a generation of B.C. activists, not least of whom is John Horgan, who was inspired by the lofty outrage of Barrett and marched down the road to join the NDP for the first time.

Spaner is no impartial observer. His stripes are on full display, but he delivers an insider’s view of the times – times that affect us still.