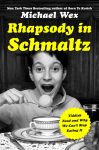

Michael Wex, author of Rhapsody in Schmaltz (St. Martin’s Press, 2016), will close the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival on Dec. 1.

“Heavy, unsubtle and, once it emerged from Eastern Europe, redolent of an elsewhere that nobody missed, the food of Yiddish speakers and their descendants is a cuisine that none dares call haute, the gastronomic complement to the language in which so many generations grumbled about it and its effects,” writes Michael Wex in the introduction of his latest book, Rhapsody in Schmaltz: Yiddish Food and Why We Can’t Stop Eating It.

“This vernacular food continues to turn up in vernacular form in the mouths of people who have never eaten it, or who don’t always realize the Jewish origin of the strawberry swirl bagel onto which they’re spreading their Marmite,” he writes. “We’ll be looking at the aftertaste of Ashkenazi food as much as at the cuisine itself. But before we can do so, we have to go back to the Bible to see why Jewish food exists and what it really is.”

Toronto-based Wex – who is the author of many books, including Born to Kvetch: Yiddish Language and Culture in All of Its Moods and How to Be a Mentsh (& Not a Shmuck) – will close the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival on Dec. 1. His topic, appropriately enough, is Jews and Food.

In Rhapsody in Schmaltz, Wex takes readers from the Exodus from Egypt – “Most national cuisines owe their character to flora and fauna, crops and quarry, domesticated animals and international trade. Jewish food starts off with a plague” – to the modern delicatessen, which “might no longer be the social hub it was for earlier generations, but the food that it serves is still recognized as Jewish, even when the ingredients are combined in ways that can’t help but pain an observant Jew.”

While written in a tongue-in-cheek manner, Wex’s love of Yiddish culture, if not of Yiddish (aka Ashkenazi) food, is apparent in every page. And each page is packed with information – that he somehow compiled on his own, without research assistants.

“Although all of my non-fiction is rooted in subjects with which I was already quite familiar, I’ve found that it’s the research itself, the jump from one source to the next, that tends to produce the sparks that lead to the better ideas,” he explained to the Independent of his creative process. “I don’t think summarized works or lists of facts provided by an assistant would allow for the immersion that I, at least, need in order to write a book.

“It generally takes me about a year to research and write a book – maybe 18 months, if you count the preliminary research that usually goes into preparing a proposal for a publisher. I generally start with a specific, if somewhat vague, question and then try to answer it: What makes Yiddish different from other languages? Why do Jewish people go on eating traditional Jewish food even when they spend most of their time finding fault with it and have abandoned the rituals and ceremonies with which such dishes were associated?”

With nine pages of endnotes and a 13-page bibliography, one might assume that Rhapsody in Schmaltz is a dry read. It is anything but – Wex’s style is completely irreverent. For example, in writing about the formation of the dietary laws, he comments, “the Israelites aren’t supposed to feel any more deprived of the right to eat certain creatures than most of us usually do about the right to get high on crystal meth or pee in the street.” He openly discusses over-the-top kosher practices, bodily functions, etc. Perhaps surprisingly, his writing hasn’t ever gotten him into trouble with his religious compatriots.

“The only ‘trouble’ I’ve encountered has arisen from misunderstanding,” he said. “For instance, I received a vehemently condemnatory email from a woman who objected to my having used the phrase ‘goat or kid’ in describing the Passover sacrifice; she was afraid that non-Jews might take the word ‘kid’ as proof that we really murder gentile children and use their blood to bake matzah. Otherwise, though, the response has been quite positive. A number of rabbis – Orthodox, Conservative and Reform – have written to tell me that they’ve used material from my books in their sermons; Born to Kvetch is frequently cited in the language column of Hamodia, an English-language ultra-Orthodox paper published in Brooklyn.

“Most feedback about Rhapsody in Schmaltz has focused either on readers’ memories of the foods mentioned or on the ritual or halachic reasons behind the forms they’ve assumed or the occasions on which they are eaten, including questions relating to their viability in a world in which most Jews are not religiously observant.”

For many readers, some of Rhapsody in Schmaltz will serve as a memory refresher of the origins of certain rules of kashrut or the types of meals that are traditionally prepared for various holidays. But there is much readers will learn and, while Yiddish food may have been a topic with which Wex was familiar before he began his research, there were a few findings that surprised him.

“The whole Crisco-Manischewitz nexus and the things that grew out of it was probably the main thing I learned; I’d known how important Crisco was for kosher marketing, but until I looked into it, had no idea of why,” said Wex. “The other thing that really shocked me when reading through cookbook after cookbook was the surprising popularity of brain latkes at one time – I knew that brains were once popular, but had never heard of consuming them in latke form.”

Tickets to the closing of the book festival, which takes place at the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver, are $24 and the event features a food reception – brain latkes not included. To order, call 604-257-5111, drop by the JCCGV or visit jewishbookfestival.ca.