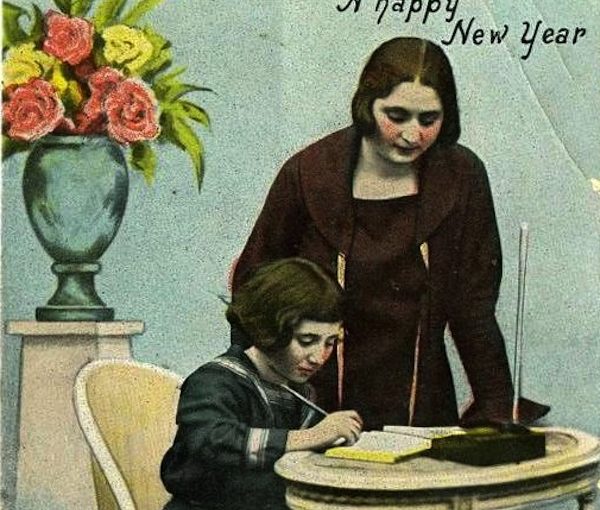

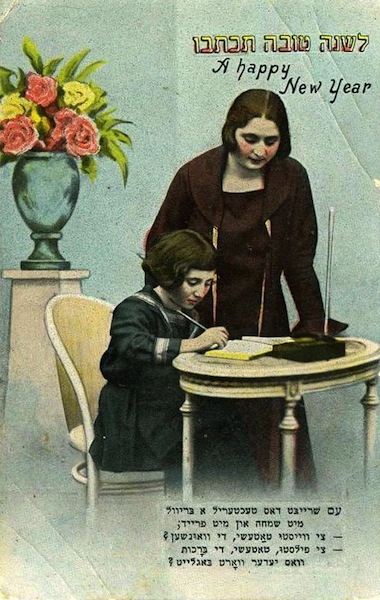

One of the family cards, produced 100 years ago, that is currently on long-term loan in the folklore department of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, on Mt. Scopus. It is from the Chaya and Chana Gitelman Collection.

Not too long ago, I was flipping through a collection of old family cards, all of which were produced 100 years ago in Eastern Europe. On the cover of one card, a young girl sits at a table writing in a notebook. Her mother stands over her, looking on. From a modern perspective, there is nothing unusual about a woman knowing how to read and write. But less than 200 years ago, this would have been considered somewhat revolutionary.

Just how revolutionary? In the article, “The History of Jewish Women in Early Modern Poland: An Assessment,” Prof. Moshe Rosman reported that, at the end of the 19th century, more than half of all Jewish girls could not read, not even in Yiddish. Rosman noted that not only was limited attention given to educating Jewish women, but that those who first wrote the history of this period, deemed it hardly worth dealing with the subject.

In early modern Poland, education for Jewish girls and women was largely designed to make them into faithful Jews who would keep female rituals. For the most part, their education was informal and conducted in Yiddish. Brenda Socachevsky Bacon states that a learned woman was an aberration and considered outside the norm. In analyzing Shmuel Yosef Agnon’s story “Hakhmot Nashim” (“The Wisdom of Women”), which was published in 1943, Socachevsky Bacon says a woman’s very presence in the beit midrash causes the men to be uncomfortable. “They view the realm of Torah study as their own, even as their own hypocritical behaviour belies their dedication to it,” she writes. “The men will not allow this discomfort to continue, even if it involves transgressing the Torah’s commandment not to embarrass another person publicly.”

Fortunately, this was not the whole story of this period. Rosman explains there were secularized school settings in which Jewish girls learned both Yiddish and European languages. The objective of these schools was modernization and general knowledge. Girls read classic European literature. In this instance, the scorn was sometimes transferred, with traditional Jewish literature viewed contemptuously.

According to Prof. Eliyana Adler (“Rediscovering Schools for Jewish Girls in Tsarist Russia”), private schools for Jewish girls were a crucial ingredient in transitioning Russian Jewry into modernity. She reports that, from 1844 to the early 1880s, well over 100 private schools for Jewish girls opened in cities, towns and shtetlach throughout the Pale of Jewish Settlement.

The educators who opened and ran private schools for Jewish girls pragmatically balanced their ideological motivations with very real concerns about funding and retaining communal goodwill. Thus, those who ran private schools offered a variety of student tracks. Rich Jews (like their wealthy Christian neighbours did elsewhere) could pay to board their children. Many schools offered weekly instruction in both music and French as paid electives.

Adler goes on to say, “at the same time, families of modest means were offered tuition payments on a sliding scale. Noteworthy, poor students were actively recruited for scholarship positions. Other schools offered less sophisticated fee scales, but clearly worked within the same framework. The rewards for having a robust student body became clear as both the government and certain private and communal bodies began to award subsidies to successful private schools.”

These private schools for Jewish girls designed Jewish studies curricula to meet the expectations of the Russian Jewish communities from which they drew their students. The curricula had to be modern and useful without being radical. Thus, efforts were made to introduce training in practical crafts; that is, crafts that could be put to use in the marketplace. In 1881, the first trade school for poor Jewish girls opened in Odessa. Thereafter, both trade schools and sections within other schools that offered more in-depth training in such skills as sewing opened with increasing frequency.

By the end of the 1890s, in Odessa alone, more than 500 girls studied in four communally funded vocational schools for Jewish girls. Jewish educators responded to the growing interest in interaction with the surrounding society by opening their private girls schools to Christian girls and by offering to teach courses in the Jewish religion in Russian schools. Prayer served as the common denominator of religious courses – the major focus of religious education was on prayer.

The teaching of Jewish history rather than simply the Torah allowed for an unprecedented degree of interpretation and even mild biblical criticism. Hebrew reading was also offered in many of the schools. Almost all Jewish girls schools offered penmanship and arithmetic.

Every private school for Jewish girls in the Russian Empire required extensive instruction in the Russian language. It was not uncommon for all general studies subjects to be taught in Russian.

Examples of the above educational transformation may be found in the bigger cities of Eastern Europe. In Plonsk (located some 60 kilometres from Warsaw), for example, toward the end of the 19th century, organizations such as Kahal Katan (literally, Small Community), educated the poorer strata of society. Also during this period, the city (which had a Jewish majority) opened a primary school for Jewish children, where some 80 pupils, mostly girls, studied in Russian. (See yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/communities/plonsk/jewish_education.asp.)

Vilna is another example. In 1915, the Association to Disseminate Education established three schools – one for boys, one for girls and one mixed – whose language of instruction was Yiddish. Also in 1915, Dr. Yosef Epstein established the Vilna Hebrew Gymnasium (high school), which was later renamed after him. The informal educational system included literature, drama, music, industrial arts and other courses. (See yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/vilna/background/20century.asp.)

According to Dr. Ruth Dudgeon (“The Forgotten Minority: Women Students in Imperial Russia, 1872-1917”), Russian women, aided by sympathetic professors, created educational institutions that evolved into universities and medical, pedagogical, agricultural and polytechnical institutes for women. Moreover, in 1916, the Ministry of Education overcame its bias against preparing women for public activity, rather than the home, and mandated the equalization of the curricula in the boys’ and girls’ gymnasia.

In the 1870s and 1880s, Jewish-Russian enrolment in the courses for women was between 16% and 21%. The imposition of quotas in the 1880s, however, reduced the number of Jewish students. But, in places where the quota was lifted, the number of Jewish women in the courses soared.

In the restricted Pale of Settlement, young Jewish women wanting to study did everything to establish residency elsewhere. The “everything” included registering as a prostitute. According to Dudgeon, one brother found out about his sister’s actions and then drowned himself in the Neva; the grieving sister, in turn, ended her life by taking poison.

As circumstances for Jews in the Russian Empire deteriorated in the 1880s, those Jews who stayed in that part of the world came to embrace new ideological solutions to the situation. In an atmosphere of violence, deprivation and brutally strict quotas in education and professions, Russian-Jewish parents wanted their children enrolled in schools where the course of study offered some hope for the future.

By the turn-of-the-century period, educators were no longer opening private schools for Jewish girls based on the old model. The schools they opened – whether they were trade schools where Zionism was taught, religiously mixed schools devoted to full acculturation, or Yiddishist schools committed to inculcating socialism – promised more than basic literacy.

In Poland, Gershon Bacon writes, “the education of Polish Jews in the interwar period was characterized … [as] the ‘victory of schooling.’ The compulsory education law of the reborn Polish republic had brought about in one generation what had eluded generations of prodding by tsarist officialdom and preaching by Jewish maskilim (people versed in Hebrew or Yiddish literature). Whether in the public schools or in the various Jewish school networks, Jewish children in Poland were educated according to curricula that deviated in almost every respect from that of traditional Jewish education. [Notably,] religious families had no objections to sending daughters to secondary schools, even though they objected to exposing sons to secular education.

“What is most striking,” continues Bacon, “are the differences in enrolment figures in institutions of higher learning. There was a much larger proportion of Jewish women students among female students as a whole (36% in 1923/1924), as distinct from the percentage of Jewish men among male students (22% in 1923/1924). It would seem that we have here but another example of a phenomenon observed in other countries, where Jewish women entered institutions of higher learning earlier and in greater proportion than their non-Jewish counterparts.” (See jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/ poland-interwar.)

So many factors about these educational statistics still need to be explored. Nevertheless, one can observe that an outcome seems to have been the creation of a modern Jewish Eastern European woman who “opened her mouth with wisdom.” (Proverbs 31:26)

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.