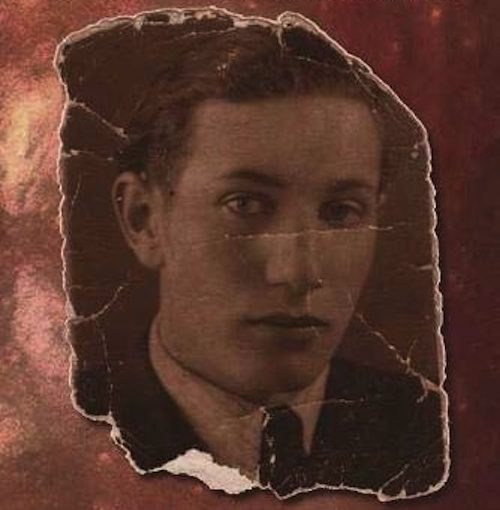

Stephen Aberle, Nicola Lipman and Geoff Berner will perform stories from Vilna My Vilna: Stories by Abraham Karpinowitz, as translated by Helen Mintz, as part of Western Gold Theatre’s Virtual Gold series.

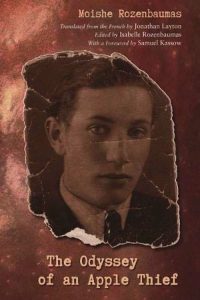

Vilna My Vilna: Stories by Abraham Karpinowitz (Syracuse University Press, 2016) is a collection of 13 short stories and two brief memoirs by Abraham Karpinowitz (1913-2004), translated from Yiddish into English by local storyteller Helen Mintz.

Thanks to Mintz, “more of us can now visit Karpinowitz’s Vilna – a city full of colourful characters, both real and not, and share in a small part of their lives.” (jewishindependent.ca/vilna-the-place-its-people) And, thanks to Western Gold Theatre, even more people will be able to visit Karpinowitz’s Vilna this Chanukah.

When Vilna My Vilna was published, actor Stephen Aberle both helped present the book and interviewed Mintz at the JCC Jewish Book Festival.

“As part of the presentation, Helen and I read excerpts from several of the stories. I was struck immediately by how engaging and naturally theatrical these stories and characters were, and I’ve been thinking ever since that a dramatic rendition would be a great thing,” Aberle told the Independent. “Then, earlier this year, Tanja Dixon-Warren, Western Gold Theatre’s artistic director, approached me with the idea of curating one of their Virtual Gold series around Chanukah time. I immediately thought of Vilna My Vilna as the perfect material for such a project, pitched it to Tanja, and she loved the idea, as did Helen. So, I set about to recruit my luminously wonderful co-presenters, Geoff Berner and Nicola Lipman, to be part of it all.

“When Helen and I first began talking about some kind of performance of these stories, we thought of Geoff and it just clicked perfectly. His ‘klezmer-punk’ material and presentation and his beautiful selection and rendition of Yiddish songs provide exactly the flavour to suit these rather gritty stories,” said Aberle. “And I had got to know Nicola through working together on the development of a wonderful new play by Manami Hara, Courage Now (coming soon to a theatre near you – but that’s another story) about Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese diplomat who helped thousands of Polish and Lithuanian Jews escape the Nazis.”

Lipman was “another perfect fit,” said Aberle. “And here we are!”

Western Gold Theatre will release individual video recordings of the selected stories, one at a time, throughout Chanukah, said Aberle, “and Geoff will frame each of them with some of his stirringly beautiful Yiddish music – an intro and an ‘extro,’ if you like – thematically linked to the content of the story. I won’t say a lot more except to add that, when Geoff and I were talking about which songs to do where, what connections to make and so forth, I think we both found it haunting and moving. Chills.”

Deciding which of the short stories to include in the production wasn’t easy.

Deciding which of the short stories to include in the production wasn’t easy.

“I have pages and pages of notes about the stories, characters, settings, arc of the narrative and so forth,” said Aberle. “In the end, I felt like a lot of my choosing was helped along by the format: we’ll be recording ourselves reading over Zoom, so we need to keep things fairly simple, with not too many characters and not too much complex action. I chose stories where the scenes tend to involve one or two characters at a time, so the performers can dig in and work off each other.

“I also tried to choose a variety of themes and moods. The stories are written against the backdrop of the writer’s awareness of what was to come: the Nazi annihilation of Vilna’s Jewish community. We have to be true to that bleak awareness; at the same time, there’s a lot of joy and humour. I tried to make choices to honour the depth and balance Karpinowitz brings to his work.”

Of the stories to be presented, the production’s press release highlights “Vilna Without Vilna,” describing it: “A Vilna native (a pickpocket in his youth, now grown up and respectable) comes back to visit his home city and finds that not a trace of what he remembers remains.”

In “The Folklorist,” a “researcher into Yiddish folklore finds himself professionally drawn to the Vilna fish market – and personally drawn to one particularly expressive fishwife.” And “Chana-Merka the Fishwife” picks up this story, “continuing the adventures of the Vilna fishwife and the school of Yiddish Institute scholars who swim after her.”

Finally, “Tall Tamara” recounts how a “Vilna prostitute and her friend find their way out of the brothel and into very different lives.”

The performances will all be online.

“Theatres are just starting to re-reopen up to in-person performances, but, for this project, we’re sticking to video presentations,” said Aberle, thanking Dixon-Warren and Western Gold “for their vision in creating the Virtual Gold series.”

“When the pandemic shut things down,” he said, “they decided they weren’t going to let it stop their work. They also decided it was important to provide opportunities to artists from a diverse spectrum of communities. And to make all the presentations free! That all takes courage and generosity of spirit.”

For those who watch the Virtual Gold series, Aberle said, “I think I can pretty much guarantee there will be laughs; there may be a few tears. It’s an honour to help share these works so more people can get to know them.”

The stories from Vilna My Vilna will be posted throughout the week of Chanukah, Nov. 28-Dec. 6, at westerngoldtheatre.org/virtual-gold. The full name of the series is Look! Listen! and Learn! Virtual Gold, and the Learn! segment will feature a video interview with Mintz about Vilna, Karpinowitz and being a translator, which will be posted on the Virtual Gold page, as well as on Western Gold Theatre’s YouTube page.