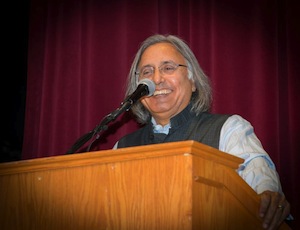

Mary Kitagawa was honoured with the

Wallenberg-Sugihara Civil Courage Award on Jan. 20. (photo by Pat Johnson)

At a convocation ceremony at the University of

British Columbia in 2012, a group of graduates stood out from the rest.

Twenty-one elderly Japanese-Canadians, ranging in age from 89 to 96, were

awarded honorary degrees in recognition of an historic injustice that had taken

place 70 years earlier.

In the winter of early 1942, right after

Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbour, the Government of Canada ordered all

Japanese-Canadians to be relocated from the coast. This included students at

UBC. For the next seven decades, the injustice went unrectified and largely

unrecognized by the university until Mary Kitagawa, a community leader whose

own family history was ruptured by the events of the war years, took up the

cause. It was her tenacity that led the university to acknowledge and make some

amends for its complicity in the injustice. It awarded honorary degrees to 96

students – most of them posthumously.

For this achievement, and others, Kitagawa was

honoured with the Wallenberg-Sugihara Civil Courage Award on Sunday afternoon,

Jan. 20. This was the 14th annual Vancouver commemoration of Raoul Wallenberg Day,

which, since 2015, has coincided with the presentation of the Civil Courage Award.

In her remarks upon receiving the award,

Kitagawa reflected on the social conditions that permitted the internment of

Canadians of Japanese descent.

“This happened because those in power in Canada

at that time forgot that this was a democratic country, sending her men and

women to war to preserve our freedom,” she told a packed auditorium at the H.R.

MacMillan Space Centre. “The excuse they used for incarcerating us was that we

were a security risk. However, if you read all the newspaper headlines of the

1930s and ’40s, you will find that the B.C. politicians’ hatred of

Japanese-Canadians was deep and abiding. They wanted to ethnically cleanse this

one small group of people from the province.”

Kitagawa said that, at a January 1942 meeting

in Ottawa to address “the Japanese problem,” a B.C. representative declared,

“The bombing of Pearl Harbour was a heaven-sent gift to the people of British

Columbia to rid B.C. of Japanese economic menace forevermore.”

“My family was swept away from our home in this

storm of hatred,” Kitagawa said. From their home on Salt Spring Island, the

family was transported to Hastings Park, in East Vancouver, which served as an

assembly point for dispersal to the interior of the province.

“Our journey through incarceration was brutal

and dehumanizing,” she said. The family was separated from her father for six

months and they feared the very worst. Eventually, the family was reunited, but

they were moved from place to place around the interior of British Columbia and

in Alberta a dozen times during seven years of incarceration.

When the War Measures Act, under which the

internment was justified, ceased its effect at the end of the war, Parliament

passed successive “emergency” laws to permit the continued incarceration

through 1947, and it was April 1949 before Japanese-Canadians were granted

freedom of movement and permitted to return to the coast. Her father and

mother, aged 55 and 50 respectively, took the family back to Salt Spring and

began all over again.

“It wasn’t just the material things that they

lost,” Kitagawa reflected. “They lost the dream for the future they had planned,

their community, their opportunities, education for their children, their

friends, their youth, their culture, language and heirlooms. But never – they

never lost their pride nor their dignity.… My parents believed in forgiveness.

Like Nelson Mandela, they believed that forgiveness liberates the soul. They

refused to look back in anger. Instead, they chose to continue to move forward

with the same resolve that helped them to survive their terrible experience.”

In 2006, Kitagawa read in the Vancouver Sun that a federal building on Burrard Street in Vancouver was being named to honour Howard Charles Green, a longtime Conservative member of Parliament from Vancouver and a leading advocate of Japanese-Canadian internment. “Immediately, I knew that I had to have that name erased from that building. To me, no person who helped destroy my parents’ dream and made them suffer so grievously was going to be so honoured.”

With help from a quickly mobilized group of

activists and sympathetic media coverage, Kitagawa successfully had Green’s

name stripped from the building, which was renamed in honour of Douglas Jung,

another Conservative MP, but the first MP of Chinese-Canadian heritage.

Kitagawa also led an initiative that saw

Hastings Park declared an historic site related to the internment.

In her talk on Sunday, Kitagawa emotionally

credited an “unsung hero,” her husband Tosh, who, among other efforts he played

in supporting Kitagawa’s activism, spearheaded the reprinting of the 1942 UBC

yearbook to include information about the internment and biographies of the

students affected. It was also through his persistence that they were able to

track down the 23 living students and the families of those who had passed

away.

The Civil Courage Award is presented by the

Wallenberg-Sugihara Civil Courage Society, which was formed by members of the

Swedish and Jewish communities in Vancouver.

Raoul Wallenberg was a Swedish architect,

businessman, diplomat and humanitarian who became Sweden’s special envoy to

Hungary in the summer of 1944, several months after the Nazi deportation of

Hungarian Jews had begun. He issued protective passports and sheltered people

in buildings that were declared to be Swedish territory, saving tens of

thousands of Jews. He was taken into Soviet captivity on Jan. 17, 1945, and was

never seen again.

Chiune Sugihara was a Japanese diplomat who

served as the vice-consul in Lithuania during the Second World War. Acting in

direct violation of his orders at great risk to himself and his family, he

issued transit visas that allowed approximately 6,000 Jewish people from Poland

and from Lithuania to escape probable death.

The award presentation was followed by a

screening of the 1995 film The War Between Us, which dramatizes the

events of the Japanese-Canadian experience through the lives of a single

family.

Councilor Pete Fry, Vancouver’s deputy mayor, read a proclamation

from the city. Consular officials from Sweden and Japan were in attendance.