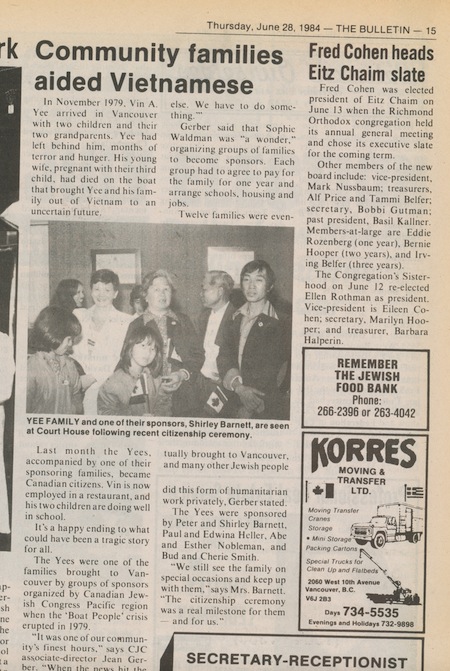

Sui Khuu and her husband Dar, with their two children. (photo from Shirley Barnett)

In the last couple of years, Jewish congregations and groups in Vancouver have sponsored refugees from Syria, acts of humanitarianism that are inspired in part from ancient and recent history in which Jewish people were strangers in a new land. But this generosity is not new. Forty years ago, in 1979, a similar phenomenon occurred with Vietnamese refugees fleeing conflict in Southeast Asia.

The so-called “boat people” – about two million Vietnamese – fled their homeland in the years following the war there, which ended in 1975. Across Canada, churches, synagogues, service clubs and other groups came together to sponsor refugees. Among these were several B.C. Jewish groups.

Forty years later, one of the refugees sponsored by a group of Jewish friends reflected on the experience.

Sui Khuu was 5 years old when she arrived in Vancouver with her 4-year-old sister Ngoc Lien (informally called Ileen), her father Vinh and grandparents Namson Khuu and Kim Thi Kiu.

“My mom passed away in [a refugee camp in] Thailand,” Khuu told the Independent recently. “She was five months pregnant. She had malaria and she passed away.”

Khuu has no recollections of her life before Canada, but deeply embedded in her memory is the warm welcome she and her family received from the Jewish sponsors as soon as they arrived here.

Four couples joined together to guarantee to the government of Canada that they would ensure the sponsored family got a secure start in their new country: Peter and Shirley Barnett, Abe and Esther Nobleman, Buddy and Cherie Smith and Paul and Edwina Heller.

With the support of Canadian Jewish Congress and Jean Gerber, who worked there at the time, numerous groups banded together to sponsor Vietnamese immigrants, including Beth Israel, Temple Sholom, the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver and Emanu-El in Victoria, among others.

“Each group had a name and our group chose the name ‘Hope,’” Shirley Barnett recalled. She has kept in close touch with the family across the decades and remembers how Sui was just 7 or 8 years old when she served as translator for her father and grandparents at government meetings and with doctors, teachers and such.

“By the time she was 9, she was the head of the family, because the grandparents never learned to speak English,” Barnett said. The father worked for the Barnetts at their Elephant and Castle restaurant for years. He is now semi-retired. The grandparents have both passed away.

“They were incredibly resourceful, successful,” said Barnett about the family. The girls finished high school and Ileen became an accountant, while Sui is coming up on 29 years as a pharmacy assistant at London Drugs.

“How did they get the strength to turn out so great?” Barnett asked. “The answer came from their grandmother. I remember one day, as a little one, Sui forgot to take her lunch to school and Grandma packed her lunch and found her way to school without speaking English and Sui told me later she found her grandmother wandering in the hallway just trying to find out what classroom she was in to bring her lunch.”

While the grandparents never learned English, they found ways to communicate.

“In those years, my ex-husband, Peter, was still fluent in French and he was able to talk to Grandpa a bit in French,” said Barnett.

Khuu recalls something beyond verbal between her grandmother and Shirley Barnett.

“I can’t imagine how she and Shirley communicated at that time but they totally understood each other,” the daughter said. “That was a great memory. My grandmother was trying to tell Shirley [something] and Shirley totally understood what she wanted her to do.”

She also remembers the Barnetts and Nobelmans picking the family up to take them to dinner, delivering Christmas gifts and taking family members to doctors’ and dentists’ appointments.

“Cherie Smith was in charge of finding them clothes,” Barnett said. “I was in charge of getting them enrolled in a preschool.”

“Shirley got a house for us on East 12th Avenue in Vancouver,” Khuu said. Both girls, now in their 40s, are married and each has a son and a daughter of their own.

Seeing Syrians coming to Canada now evokes memories for Khuu.

“It’s hard when they have young families like what my grandparents and my dad went through,” she said. She is saddened when she hears comments that are unwelcoming toward new Canadians and sees the circle of life in the next generation of refugees finding a home here.

Barnett is effusive about how Sui and Ileen have turned out: “By luck or determination or resilience or whatever they had, they turned out really well. They are just lovely, responsible, charming, caring people.”