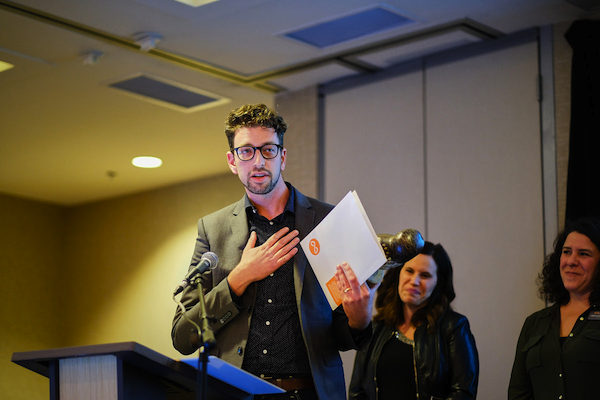

Marsha Lederman (photo by John Lehmann/Globe and Mail)

A few years ago, Marsha Lederman went with her mother, two sisters and a cousin on the adult portion of the March of the Living, which included a walk between the two main camps of the Auschwitz-Birkenau complex.

“The march from Auschwitz to Birkenau was somber and sorrowful, but it was also so empowering,” she recalled at the annual High Holidays Cemetery Service at Schara Tzedeck Cemetery in New Westminster Oct. 6. “We were marching with a statement to the world and a comforting message to the souls whose lives had ended so brutally on those grounds: ‘We are here, we are still living, we are multiplying, we remember you.’”

The family group proceeded to Radom, the town outside Warsaw where Lederman’s mother had grown up. The man who lived in the apartment where she had lived allowed them in and Lederman’s mother recounted her family’s years there.

“It was joyous,” Lederman said. “We were still on a high when we visited the memorial for the Radom Jews killed in the Holocaust. As I recall, it was in a fairly large square and seemed a little neglected. We were looking at this lonely memorial, the five of us women, when a group of, I would say, teenage boys began chanting something nearby. I don’t speak Polish, so I couldn’t understand what they were saying. But I did understand one thing: ‘Auschwitz-Birkenau.’ I don’t think they were offering their condolences.”

She reflected on the way she responded in that moment.

“We hurried away and said nothing. It was a safe thing to do, for sure. But, if that happened to me today, I would not walk away. I am done with walking away. Would I have put us in danger if I had turned around and confronted those boys? Maybe. But I know now that the real danger is in remaining silent.”

Lederman is the Vancouver-based Western arts correspondent for the Globe and Mail. Her father was born in Lodz, Poland, on erev Yom Kippur 1919. Her mother was born in Radom, Poland, in 1925. All four of their parents were killed in gas chambers at Auschwitz and Treblinka, as was Lederman’s father’s sister and little brother, and her mother’s little brother.

Lederman’s parents met in Germany after liberation and had one daughter there before moving to Canada, where they had two more daughters.

Lederman reflected on recent antisemitic incidents in North America and Europe, as well as her own encounters with antisemitism and racism, including a harrowing verbal attack on an Asian woman on the Skytrain at rush-hour, an incident in which Lederman was the only person to intervene.

“We have a duty to speak up,” she said. “We have a responsibility. This is our inheritance. I never had a bubbe or zadie to hug me or spoil me on my birthday or cook chicken soup for me. There’s nothing in my home that was theirs. I did not receive a single heirloom. But I did receive an inheritance – a duty to protect others from hate…. That is my inheritance and that is their legacy. Enough. Never again.”

She recalled being stunned during an interview with famed Vancouver photographer Fred Herzog, who died last month. Chatting after the main interview, Lederman asked the German-Canadian if he had experienced anti-German sentiment when he arrived here after the war. He launched into a discourse on the “so-called Holocaust” and said Jews died in the camps mostly because of lice and because Allied bombings prevented food from getting to them. Lederman agonized over whether to expose the admired photographer, eventually writing the story, for which she has been subjected to a range of criticism.

“Well, I have had enough,” she said. “And I’m going to fight to tell those stories and expose antisemitism and Holocaust denial and racism. I am not going to be quiet anymore. I think of all that was lost in the gas chambers; all the lives, of course, but also all the potential. With those millions of lives extinguished, what was lost with them? Poems were never written, beautiful artworks that were never painted, the cure for cancer, for Parkinson’s, the answer to the climate crisis?

“It was not just the people who were murdered that the world lost. It was all of their descendants and all of their descendants and all of that potential.… I talk about this because of what this leaves on our shoulders. I interviewed a Nisga’a poet, Jordan Abel, and he used a term to describe himself that I have adopted. He calls himself an intergenerational survivor of residential schools, which makes me an intergenerational survivor of Auschwitz. I do not take this lightly. With my parents’ survival came a hefty responsibility on me and on all of us who are descendants.”

At the service, Jack Micner, who led the ceremony and is also a member of the second generation, outlined a litany of antisemitic incidents and comments in Europe and North America in recent weeks.

“I suspect that those of our parents resting here in this cemetery would be furious to see what’s going on across the world,” he said. “We have to continue doing the type of work that VHEC [Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre] is doing in as many ways as we can think … it falls on us, because nobody’s going to do it for us.”

Rabbi Shlomo Estrin reflected on the loss of Chassidic communities during the Holocaust. Cantor Yaacov Orzech chanted El Maleh Rachamim.

Names were read of community members who have passed since the last High Holidays and a moment of silence was observed for the six million.

The Mourner’s Kaddish was recited by Jeremy Berger, a grandson of a Holocaust survivor. After the service ended, the Mourner’s Kaddish was also recited at the Holocaust Memorial in the cemetery.

The annual event is presented by the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre with Congregation Schara Tzedeck and the Jewish War Veterans, and with support from the Jewish Community Foundation of Greater Vancouver.