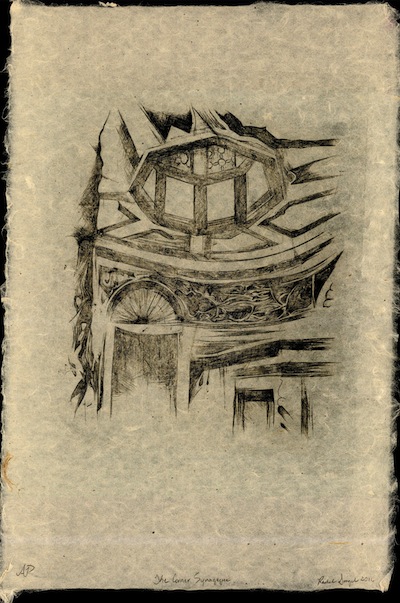

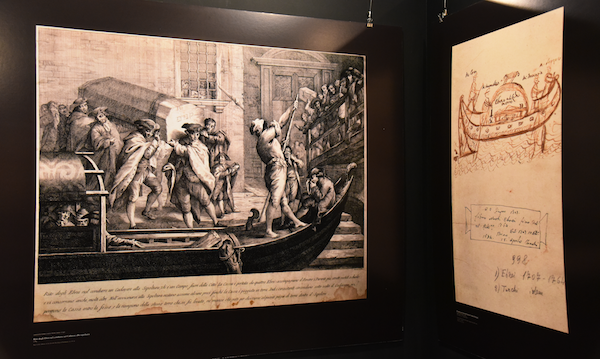

A page of the digital interactive installation of the domestic space of the Jewish ghetto, which was created by camerAnebbia. Part of the exhibit Venetian Ghetto: A Virtual Reconstruction: 1516-2017, which is at the Italian Cultural Centre’s Il Museo until Oct. 30. (photo by Cynthia Ramsay)

The Venetian ghetto – a segregated enclave for Jews and the one from which the very name “ghetto” emerged – was created 500 years ago. An exhibit at Vancouver’s Italian Cultural Centre tells the history of the ghetto and is one of a number of local cultural events this year marking the half-millennium since the notorious decree.

The Venetian Ghetto: A Virtual Reconstruction: 1516-2017 opened at the centre’s Il Museo this summer. It is an abridged version of a larger exhibit showing concurrently at the Doge’s Palace in Venice, said the museum’s curator, Angela Clarke.

Clarke and Il Museo had wanted to do something around the topic of the ghetto in part because of a connection with a member of Vancouver’s Jewish community. When the late renowned University of British Columbia architecture professor Dr. Abraham Rogatnick passed away in 2009, he left his collection of Venetian books and other materials to the museum.

“A lot of the prints we have in the hallways are from his collection,” said Clarke. “Venice was his specialty.”

Rogatnick took his architecture classes to Venice and was also noted for turning his lectures into theatrical performances, accompanied by moody lighting and complementary background music. (After his retirement, he became immersed in Vancouver’s alternative theatrical scene, depicting, as he put it, “usually dying old men.”)

“We have, for a long time, wanted to do something in honour of Abraham Rogatnick,” said Clarke. When she discovered that the Doge’s Palace was planning an exhibit to mark the 500th anniversary, she contacted the institution. They agreed to reproduce a version of the exhibit tailored to Il Museo’s space.

It was the palace’s 16th-century resident, Lorenzo Loredan, the doge of the Republic of Venice from 1501 until his death in 1521, who determined that Jews should be segregated from the general Venetian population.

Although the origin of the term “ghetto” is disputed, many accept the view that it comes from the Venetian dialect’s word ghèto, foundry, which was the neighbourhood in which Jews were confined. Jews were allowed access to the city during the day, but were restricted to the ghetto at night. Space limitations in the ghetto led to upward expansion, including multi-storey homes and buildings, a unique architectural approach to that date.

“They built upwards to accommodate their family life and their businesses, so you got these very, very high staircases in buildings and they just built upwards,” Clarke said. “For the Jewish community, it’s all about going up stairs. I think a lot about the aging people in these families. What happened to them? What would an 80-year-old do? How would they negotiate that and go about their family life and business? And the stairs are incredibly steep. That was just their everyday life.”

The exhibit has four parts, including an interactive exploration of the ghetto’s synagogues through a virtual reconstruction. The architecture of the ghetto, the cemeteries and “the ghetto after the ghetto” – the fate of the area after Napoleon conquered Venice and emancipated the city’s Jews in 1797 – round out the exhibit.

The ghetto was remarkably multicultural, Clarke emphasized.

There were four main cultural groups that came to Venice, she said. “There were the Italian Jews, there were the German Jews, there were the Spanish Jews and then there were the [Levantine] Sephardic Jews, and they all came to Venice, so there were a number of synagogues and each synagogue was like a different cultural centre, based on your group, because each synagogue, of course, had schools. You have Hebrew but then your own cultural language. So the synagogues really did deal with a diverse group of people who came.”

Jews began gravitating to Venice as early as the 900s, with a surge in the 1300s and then again after the expulsion from Iberia.

The segregation of Jews was premised on economic concerns, said Clarke, with restrictions on professional activities that pushed the Jewish residents into dubious roles like moneylender. As in so many instances across European history, Jews were forced to wear differentiating articles of clothing; in Venice’s case, a red hat. The exhibit demonstrates the constancy of the compulsory topper while also depicting changing styles across centuries.

“The fashions change but the red hat stays the same,” Clarke says guiding visitors from one painting to another. “The woman over there, she’s very Renaissance. Over here, it’s the 1700s and he’s still wearing the red hat but the fashion has changed dramatically.”

Napoleon liberated the Jews, but he had somewhat bigoted notions of the city of Venice.

“He called it the drawing room of Europe, depicting Venice as this beautiful little elegant community,” Clarke said. “However, I’ve been reading Florence Nightingale and she [observes that] referring to something as a drawing room is a pejorative term. For a man to be in a drawing room is basically to say that he’s effeminate.

“When you look at it in that historical context – especially when you’re dealing with a megalomaniac who’s got basically size issues – it’s a veiled term,” she said, laughing.

The exhibit at Il Museo coincided with the Stones of Venice exhibit at the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver (profiled in the Independent Aug. 18) and performances of Merchant of Venice and Shylock as part of this year’s Bard on the Beach (reviewed July 21).

“It all just seemed to come together, which is very bizarre,” said Clarke. “It doesn’t often happen that way.”

The Venetian Ghetto: A Virtual Reconstruction: 1516-2017 continues until Oct. 30 at Il Museo in the Italian Cultural Centre of Vancouver, 3075 Slocan St. More information at italianculturalcentre.ca.