International Holocaust Remembrance Day was commemorated here on Jan. 25 with a ceremony at the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver. Holocaust survivors lit candles of remembrance and there was a moment of silence followed by Kaddish; Nina Krieger, Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre executive director, read a proclamation from Mayor Gregor Robertson; and a screening of the film Numbered followed, in which survivors of Auschwitz, their children and grandchildren reflect in often unexpected ways on the meaning of the numbers the Nazis tattooed onto their victims.

Vancouverite Robbie Waisman, who is a child survivor of Buchenwald, delivered remarks before the film. With permission, the Independent is privileged to publish a slightly edited transcript of his words:

I am honored to be with you this evening. This film speaks about numbers. I have not seen the film, but I have experience with numbers.

Numbers that have been given to us in the camps have two very significant meanings. They were very dehumanizing. They robbed you of your feelings as a person. Your humanity as a human being was taken away. And as long as you remained healthy and were able to work, in that sense the number given to you made it possible to remain alive and continue to live and hope to survive.

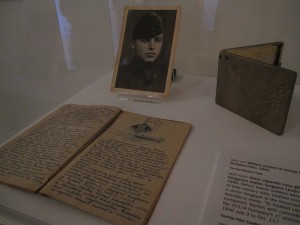

When I lived in France after liberation, they gave us identification cards. It allowed me to get around every day. The police issued it to me on June 9, 1947. I had to have it renewed every year. This was important to me. This was my first ID card, so it is hard to explain how I cherished this card. It meant that I was no longer just a number. It meant that I was a person, that I was a person of value. It proved I had a name and an address. I was so proud to have it. It gave us back some of the dignity we had lost. It gave us back our humanity.

Every time a ghetto was being liquidated, there was a selection of men and women who the Nazis selected to work. Those would be spared and taken to the munitions factories to replace other workers who they perceived as not being strong enough to continue working.

I myself have gone through three of those selections successfully with my father alongside with me.

All of us Jews who were no longer capable of working were eliminated in the most horrific way. I am not going into details – the pain always resonates.

The Nazis decided who qualified to live and work, and others were sent to the gas chambers. Six million of our people, of which 1.5 million were children, were brutally murdered. I represent the seven percent that managed to survive.

The Nazis and their collaborators murdered my mother, father and four older brothers … my uncles, aunts, cousins and friends who had been my schoolmates, and on and on.

Getting back to numbers…. When I read that many second- and third-generation survivors are [tattooing] their fathers’ and grandfathers’ numbers on their own arms and chests, I was upset.

Upon further research and reflection, I came around and now admire all those that have done this noble task. It is strange and amazing how, after all the years, those numbers have taken on a new meaning and brought change to what we think about those horrific years.

The book God, Faith and Identity from the Ashes is a reflection of children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors. Rabbi Dr. Bernhard Rosenberg, from Beth El New Jersey, who is the son of survivors Jacob and Rachel Rosenberg, wrote: “Growing up, I constantly looked at the numbers on my father’s left arm, which he received in Auschwitz. Those numbers instilled in me the urge to fight for the state of Israel and against antisemitism wherever it may occur. I became a rabbi because of those numbers.”

Here is my own experience with numbers. Imagine being a 14-year-old boy. Imagine having been in hell and back over four years of this boy’s life working in Germany’s ammunition factories, being hungry, starved, emotionally exhausted, physically weakened, deprived of every human emotion. Imagine being so brutalized and dehumanized that you begin to believe that you are no longer human. In spite of it all, I never lost hope of being reunited with my family.

Hope! – a very powerful motivation.

The emergence of the enormity of the Holocaust became known to us and we had to find a way to deal and cope with the huge loss of all our loved ones murdered by the Nazis. How are we going to live with all those horrors?

April 11 will be the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Buchenwald.

Would you believe, Gloria [Waisman’s wife] and I are invited by the German government to come to Weimar for this special occasion, where I am also invited to speak to German teenagers. I will share my experience in that infamous and dreadful place where death was a constant companion.

I celebrate April 11 as my birthday, for that day I was reborn again into freedom.

When the Americans liberated Buchenwald, we were euphoric! I will never forget the feeling! The soldiers were larger than life. They symbolized freedom, a new beginning! I tried to communicate with them, but had no words.

For the first time, I saw black men among the soldiers. Since I had been tormented by white persons and had never seen a black person, I thought that angels must be black!

The soldiers looked around and were surprised to find youngsters like myself. They wanted to know, Who are these kids? Where do they come from? What are their nationalities? Why are they here? What are they guilty of? What was the crime they committed?

Ultimately – a few days later – some men arrived to sort out the puzzle. They proceeded to make a list of our names and when my turn came and I was asked my name, I blurted out #117098, the number given to me. My name as a human was erased. I was surprised that they wanted my name not my number. So, you see here, again, the numbers are part of our stories.

When I think back, it was an extraordinary time, full of promise and hope. But it was also bittersweet. Those of us determined to survive had to focus all our efforts towards survival. We wanted to go home and be reunited with family. We soon realized that home was no more and that families we loved had been brutally murdered.

But after emerging from the abyss, thoughts and feelings returned.

Questions bombarded me. What now? Where is my family? Has anyone survived? If not, what is the point of my own survival?

Those wonderful memories of home no longer existed. Everything shattered.

How will I recapture feelings, so that I could cry and laugh again? How do I learn to love and trust again?

It was not easy to relearn the ordinary skills of life that had been shattered over a six-year period. We had to put our numbers aside, reclaim our names and that of our families and move forward.

We were also sure that when the American soldiers … when they saw the consequences of Nazi racism and brutality … that they would ensure that such things would never happen again. We, the survivors, were certain that the leaders and the citizens of the world would say “Never again!” and commit themselves to turning those words into reality.

Never again! Noble, thought-provoking words, but only if we act upon them. Only then do these words become meaningful.

Today, almost 70 years after my liberation, the promise of “Never again” has become again and again!

There have been a number of situations that have tested the world’s resolve … in Cambodia, the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and now in Darfur, Syria and so many other places, people have been, and continue to be, the victims of genocide.

My eyes have seen unspeakable horrors! I am a witness to the ultimate evil! I am a witness to man’s inhumanity to other human beings! To this day, I cannot grasp how I managed to go through hell and survive.

The promise of being reunited with my family, all my loved ones, was the strong motivator for not giving up, for not losing it and falling into despair. After having come out of the abyss, I remember thinking, What now? I must go home – my family is waiting for me.

Then the questions began. Where are our loved ones? What happened to them? So much devastation! How to cope? So many losses, including our humanity. We became angry and outraged.

We were 426 youngsters among 20,000 adults in Buchenwald. We were brought to Ecouis, France, for our recovery and were told by psychologists that we had become sociopaths who would never recover.

Most of us forged ahead in school and business, raised families and contributed to our communities. In fact, we count among the Buchenwald children such personalities as my friend Elie Wiesel, Nobel Prize winner; and Lulek, Israel’s recent chief rabbi, Israel Meir Lau, and his brother Naphtali.

Simon Wiesenthal, of blessed memory, said, “I believe in God and the World to Come, and when they ask me what did you do? I will say, I did not forget you.”

I want to end with my friend Elie Wiesel’s words: “Zachor, remember, for there is, there must be, hope in remembering.”

The commemoration was presented by the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, in partnership with the Norman and Annette Rothstein Theatre and the Vancouver Jewish Film Festival, and with funding from the Jewish Federation of Greater Vancouver and Rita Akselrod and family, in memory of Ben Akselrod z”l.