Planting trees as a community project in Jerusalem. (photo by Ariella Tzuvical)

Are Israeli city-dwellers still attached to the land? The answer is yes, but the connection to the land plays itself out in a surprising way.

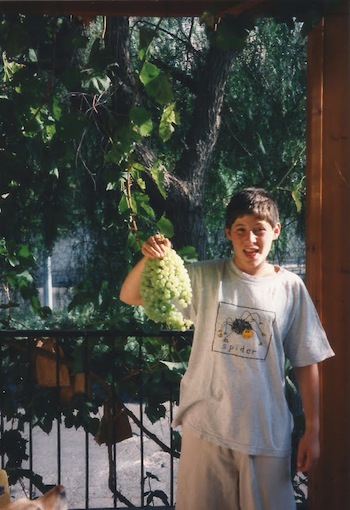

By and large, today’s Israelis are an apartment-bound lot, but many dream of having a house with a garden. Those who are lucky enough to have a small garden – or an apartment with a patio – plant flowers and even grow fruit. Depending on the season, many Israelis grow grapes, oranges, tangerines, pears, grapefruits, lemons, kumquats, olives and pomegranates. Interestingly, some of these items have been grown in Israel since ancient times: “a land of wheat and barley, and grapevines and fig trees and pomegranates; a land of olive trees and honey … you shall eat and be satisfied.” (Deuteronomy 8:7-10)

Community gardening is a budding and not insignificant phenomenon taking root in Israeli cities. In Jerusalem alone, there are 70 community gardens. Municipalities, community centres, local branches of national nature preservation organizations (like Hachevra L’haganat Hateva), pro-environment charitable bodies (like Keren Sheli) and the Ministry of Environmental Protection are teaming up to help urban residents create these gardens. They are assisting interested apartment dwellers by providing seed money, land or know-how to get projects off the ground and onto porches, patios and even rooftops.

Why do urban Israelis grow fruits and vegetables? One young mother from Tel Aviv commented in a Yediot Ahronot article that she wants her children to understand that produce does not come from the supermarket.

Of course, most people want to use their homegrown fruits and vegetables in their regular cooking and preserving. But some grow fruit, such as the pomegranate, for special holiday consumption. For these gardeners, the following Rosh Hashanah blessing takes on added significance: “May the desire of our G-d and the G-d of our Fathers be to increase our merit like the [seeds of the] pomegranate.”

The Jerusalem-based Melamed family says it gardens for exercise, art and culture. They maintain that gardens produce cultured people. Another Jerusalemite looks at her blossoming pear tree and says that keeping a garden enriches a person’s life.

Although Israel, like most other Western countries, has largely switched from being an agrarian society to a technological society, places like the Jerusalem Botanical Gardens believe that gardening has a place. With that in mind, the facility has hired staff to make urban gardening more relevant to those living in Jerusalem.

As well, many Israelis seem to maintain the notion that G-d provides the ingredients for surviving off the land. Thus, when Jews celebrate the rebirth (or reproduction) of the Jewish year, they read: “See, I give you every herb, seed and green thing to you for food.” (Genesis 1:28-30) The annual Torah reading about producing in order to have food has helped fix the idea in the Jewish psyche.

Dr. Rabbi Dalia Marx wrote in A Torah-Prescribed Liturgy: The Declaration of the First Fruits: “The declaration of the first fruits is a bold text.” In Deuteronomy 26, Moses addresses the Israelites on the plains of Moab, “calling upon the Israelites wandering in the wilderness with no permanent ties to the earth to imagine themselves as farmers securely living in their own land. But simultaneously, the text demands of farmers living in their own land that they remember their days as wanderers in the wilderness – and necessarily … ponder the fragility of their own lives.”

When bringing the first fruits of the land to the Temple, the farmer thanks G-d for the bounty in a manner providing for “the entire recapitulation of national history.” In essence, “the farmer teaches himself that the final chapter in the national story is unfolding in real time.”

It should not come as a surprise that Israelis still seriously celebrate the agricultural component of their Jewish pilgrimage holidays. At Sukkot, Israelis everywhere erect sukkot, or booths, just as growers did in their fields thousands of years ago. And, of course, during Sukkot, observant Jews around the world purchase and bless the following combination of plants and fruit: the etrog (citron), lulav (palm), hadas (myrtle) and aravah (willow). These are known as the arbah minim, the four species.

The Passover seder plate contains greens that remind Jews that spring has arrived in Israel, while Shavuot commemorates the harvest that began around Pesach time and ended seven weeks later. For many years, this agricultural holiday had special meaning for those living in Israel, as the early settlers lived off farming. Today, Israel holds a variety of festivals showing off the bikurim, or first produce of the season. These holiday celebrations focus on the production of dairy products and honey.

In early winter, Jews throughout the world celebrate Chanukah by eating foods prepared in oil. Some food researchers maintain this may be related to the fact that Chanukah coincides with the end of the olive harvest. In late winter – except during the Shmitah year, when Jewish law dictates that the land be given a chance to rest – Israeli schoolchildren are out in force planting new trees on Tu b’Shevat, the birthday of the trees, which is increasingly celebrated with a special seder.

Avi Eshkoli, a veteran Jerusalem-area gardener, reported that he had seen more people trying to observe the Shmitah than he had ever witnessed before. He noted that the practice covers the gamut of Israeli religiosity and spirituality.

Part of what continues to tie Israelis to gardening is deeply implanted in Jewish tradition. There is no escaping the fact that Jewish holidays are connected to natural events. Every Jewish holiday begins with a blessing over the wine, the fruit of the vine, and special holiday texts such as Shir HaShirim (the Song of Songs), which is read on Pesach, and Megillat Ruth (the Book of Ruth), which is read on Shavuot, are ripe with references to gardens and fields.

The blessing over the wine is even part of the Jewish wedding ceremony. And, moreover, before the Sabbath eve meal, Jews recite the Kiddush that recalls G-d’s creation. Thus, at least once a week, many Jews are reminded of the process of birth, growth and production in the natural world.

Dr. Rabbi Marx points out that the “new” liturgy for Yom Ha’atzmaut, Israeli Independence Day, incorporates the concept of first fruits, reflecting “that we are home now, but acknowledg[ing] both the process leading to this moment and the fact that the dwelling in the land of Israel is not obvious or guaranteed.”

For Israelis then – and perhaps for many Jews in the Diaspora – urban gardening is not just about growing plants, but about growing spiritually as a people.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.