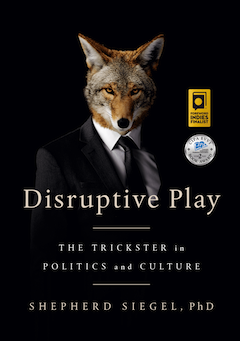

Shepherd Siegel, author of Disruptive Play. (photo by Laura Totten)

Shepherd Siegel is a hardcore idealist. At least, it would seem so, based on his book Disruptive Play: The Trickster in Politics and Culture (Wakdjunkaga Press, 2018).

“What if we didn’t take everything so seriously and capitulate to the competitions of war and business?” he writes. “What if we let our utopian dreams and desires out to play, out of the box? What if we did more than talk about it and constellated our lives around play and art instead of work and commerce?”

While all about play, Siegel’s 358-page analysis is more academic than whimsical. A writer, musician and educator, he earned his doctorate at University of California Berkeley and has more than 30 publications to his credit. Quickly into the book, he admits the inherent difficulties in writing on this topic: “By attempting to put play, an irrational activity, into the rational fictions of words, I fear that naming this magic will dispel it.” And, to some extent, it does, but his prose is clear and engaging; his examples well-explained and well-researched.

Siegel defines three types of play. Original play is what kids up to three years old do; it has no purpose except fun, it is spontaneous and creates a sense of belonging. Cultural play entails games with winners and losers; it involves learning skills through practise, it comprises rules and moral lessons. Disruptive play “disrupts the normal functioning of society”; it is “resistance to contest-based society and a public affirmation of the natural play element that pervades all life.”

Disruptive players – or tricksters – have existed throughout history, in both oral and writing-based cultures. Siegel gives some 25 examples, beginning with the trickster Wakdjunkaga, whose precise origins are unknown, but whose story comes from the Winnebago (or Ho-Chungra) tribe, “which emerged in northwestern Kentucky in roughly 500 BC. From 500 AD and for about a thousand years, they lived in what is now Wisconsin.” He ends with the Yes Men: “Jacques Servin and Igor Vamos are known by many aliases, but they are Andy Bichlbaum and Mike Bonanno when they are the Yes Men,” and they operate under the motto, “Lies can expose truth,” using guerilla theatre and other tactics, Siegel writes, to “embarrass and proclaim the sins of those who would wage unjust wars, destroy the environment, or cause the suffering and death of other people.”

Siegel discusses in depth several trickster tales from various parts of the world. He analyzes King Lear’s Fool, Bugs Bunny and The Simpsons in this context, as well as real people, such as Alfred Jarry, Marcel Duchamp, Andy Kaufman, Abbie Hoffman and others, and movements like dadaism in art, the Beat Generation in literature and rock and roll in music. He also offers a couple of models on which a play society could be based: the Fremont Solstice Parade in Seattle and Burning Man in Nevada.

Siegel discusses in depth several trickster tales from various parts of the world. He analyzes King Lear’s Fool, Bugs Bunny and The Simpsons in this context, as well as real people, such as Alfred Jarry, Marcel Duchamp, Andy Kaufman, Abbie Hoffman and others, and movements like dadaism in art, the Beat Generation in literature and rock and roll in music. He also offers a couple of models on which a play society could be based: the Fremont Solstice Parade in Seattle and Burning Man in Nevada.

While acknowledging that there are many problems in the world, Siegel foresees a time when society will be able to meet all of its members’ basic needs. When this time comes, he writes, “the greatest remaining problem will be one of establishing and maintaining societies of trust. Play, as we shall see, absolutely requires trust in order to thrive, even to exist.” However, until that time comes, disruptive play – which threatens power brokers and structures – is a dangerous venture.

“Playful adults, artists, the poor, people with disabilities and deviators are all sent to the margins,” writes Siegel. “From the 17th-century development of military tactics and the industrial revolution of the 18th century came a more prescriptive sense of the normal and the suppression of carnival celebrations and urges … thus the binding of the Trickster spirit. The concentration of power, by its very nature, requires divesting this spirit, treating the Trickster as the Fool or court jester. But eventually the Fool makes fools of those who would constrain, punish and repress Trickster spirit.”

Unfortunately, while most of the tricksters Siegel highlights do indeed have their time in the sun and they manage, for awhile, to speak truth to power and get people to question their values and society’s direction, their lasting impact has been minimal, even if they themselves have proven memorable. The potential for building a play society – given Siegel’s convincing argument that capitalism or commercialism and play are antithetical – is a long shot. The models of Fremont and Burning Man are small-scale, time-bound events and do not seem feasible as models for society as a whole, for any length of time.

That said, Siegel’s is an exciting vision. “As (and if) our society achieves economic, environmental and social balance, the search for a meaningful life will take on greater importance and become more complex,” he writes. In this utopia, play, which “has meaning but not purpose … is the perfect antidote for existential crisis in a world of questionable purposes. Only by entering a state that discards purpose – that plays – might our true purpose be discovered.”