Left to right are Sam Sullivan, Glen Hodges, Cynthia Ramsay, Margaret Sutherland and Shirley Barnett with one of the Mountain View Cemetery ledgers. (photo by Lynn Zanatta)

“When we were restoring the Jewish cemetery at Mountain View, we spent two years going through City of Vancouver material trying to determine if the city actually had something in writing to prove the legitimacy of this Jewish section since 1892,” Shirley Barnett, who led the Jewish cemetery restoration project, told the Jewish Independent in an email. The committee couldn’t find anything in the city records.

While this lack of documented history lengthened the restoration agreement process significantly, it did not halt it. Barnett, as chair, opened the first meeting of the restoration advisory committee on Feb. 13, 2013, and the Jewish cemetery at Mountain View was officially rededicated on May 3, 2015. However, if the committee were to have started its work today, the information it sought would have been found, and the process would have moved much more quickly.

Sam Sullivan, member of the Legislative Assembly (Vancouver-False Creek) and former mayor of Vancouver, founded the Global Civic Society in 2010. As part of its mission to encourage “a knowledgeable and cosmopolitan citizenry to make strong connections to their community,” the society leads several initiatives, including Transcribimus, “a network of volunteers that is transcribing early city council minutes and other handwritten documents from early Vancouver, and making them freely available to students, researchers and the general public.”

Transcribimus project coordinator Margaret Sutherland has transcribed at least 155 sets of Vancouver City Council minutes. It was she who found what Barnett and her committee were looking for – in the council minutes of June 6, 1892. On page 32 of the minute book, it is recorded that correspondence had been received, “From D. Goldberg asking the council to set aside a portion of the public cemetery for the Jewish congregation,” and was “Referred to the Board of Health.”

Two weeks later, the minutes of June 20, 1892, note that the health committee had resolved, among other items, “[t]hat the piece of land selected by the Jewish people in the public cemetery be set aside for their purposes.”

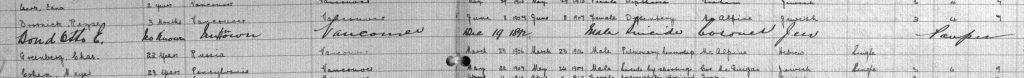

![photo - In addition to the transcribed council minutes, transcribimus.ca includes photos of the minute book pages. This image is of the June 20, 1892, minutes, which note that the health committee had resolved, among other items, “[t]hat the piece of land selected by the Jewish people in the public cemetery be set aside for their purposes.”](https://www.jewishindependent.ca/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/jan-18-cov.18.cemetery-1892-06-jun-20-vancouver-city-council-minutes_page-50-cropped-w-oval.jpg)

The cemetery first appears to have come up a few years earlier. In the July 29, 1889, council minutes, there is reference to a letter: “From L. Davies on behalf of the Jewish congregation of the city of Vancouver requesting council to set apart about one acre and a half in the public cemetery for members of the Hebrew confession. Referred to the Board of Works.”

In an email to Barnett, Sutherland wrote, “There doesn’t seem to be any indication from city council minutes that the Board of Works ever followed up on the above request. Although [Jewish community member and then-mayor] David Oppenheimer was on the Board of Works for that year, so was his opponent, Samuel Brighouse.”

On Dec. 7, 2018, the Jewish Independent met with Barnett, Sullivan, Sutherland, Lynn Zanatta (Global Civic Policy Society program manager) and Glen Hodges (Mountain View Cemetery manager) at Mountain View. In documents she brought to that meeting, Sutherland explains that Oppenheimer “declined to serve as mayor again at the end of 1891, citing poor health as his reason for retiring. Fred Cope was elected mayor in 1892 and served till the end of 1893.” So it was Cope who was mayor when the Jewish cemetery was established; Oppenheimer was Vancouver’s second mayor (1888-1891) and Malcolm Maclean its first (1886-1887).

The first interment at Mountain View Cemetery was Caradoc Evans, who died at nine months, 24 days, on Feb. 26, 1887. The first Jew interred in the cemetery is thought to be Simon Hirschberg, who “died of his own hand” on Jan. 29, 1887, and was, according the plaque erected by the cemetery in 2011 (the cemetery’s 125th year), “intended to be the first interment,” however, “rain, a broken carriage wheel on a bad road and his large size all contributed to him being buried just outside the cemetery property,” where he was “long thought to have been left near the intersection of 33rd and Fraser” until his body was moved into a grave on cemetery property. Oddly enough, the first Jew to be buried in the Jewish section was Otto Bond (Dec. 19, 1892), who also took his own life.

So far, since its inception in 2012, Transcribimus has seen more than 300 transcripts produced by almost 40 volunteers, although a handful of them are responsible for the lion’s share to date. Many people have donated their time, technical advice and, of course, funds to the project. Barnett sponsored the transcribing of the city council minutes for 1891, and fellow Jewish community member Arnold Silber sponsored the transcription of the 1890 minutes. A few other years have also been sponsored, including 1888, by the Oppenheimer Group.

About nine years’ worth of minutes have been transcribed (1886-1893 and 1900), leaving much more work to be done, as the city kept handwritten minutes until mid-1911. After that, minutes were typewritten and these documents can be scanned and read with OCR (optical character recognition), said Sutherland.

The Transcribimus website (transcribimus.ca) is one of the best-designed sites the Independent has come across. It is both visually appealing and incredibly easy to use. In addition to the transcribed council minutes, it includes photos of the minute book pages. As well, it features letters from Vancouver’s early years, historical photographs and a few videos, including a film by William Harbeck of a trolley ride through Victoria and Vancouver in 1907, which has had speed corrections and sound added by YouTuber Guy Jones. (Astute viewers will see that the trolley is driving on the lefthand side of the road. British Columbia didn’t switch to the right until 1921-22.)

In the material Sutherland brought to the December meeting at the cemetery office, she included the transcription of the short letter that city clerk Thomas McGuigan wrote on June 23, 1892, in response to Goldberg’s letter that was mentioned in the council minutes. In it, McGuigan confirms “the grant made by council to the people of the Jewish faith of a piece of land in the public cemetery,” but adds that “they will be unable to give you title for the same, as the land was set apart by an Order in Council of the provincial government for burial purposes and they refuse to give any other title.”

Sutherland hadn’t come across Goldberg’s letter, that of Davies or any response to Davies. It’s likely that these letters have been lost or destroyed, but they might turn up in another file, she said.

However, Sutherland did find a brief letter to the editor of the Vancouver Daily World newspaper, dated Nov. 1, 1898, from L. Rubinowitz, which she emailed to the Independent. Rubinowitz wanted the application for the Jewish cemetery by “a certain number of Jews of this city” to be refused. In his view, “all the Hebrews of this city are not combined as one body” and “To avoid trouble between them and for the sake of peace, as one party will claim that they have the sole right to it, the other party will claim that they have the sole right to it, therefore, as it is now under the control of the city, we are well satisfied to let it remain so, as in my opinion the city will have no objections for us to make any improvements if necessary.”

The old joke comes to mind of the Jewish man who, when stranded on a deserted island by himself, builds two synagogues – the one he’ll attend and the one he won’t set foot in. Community cohesiveness is a heady task; always has been, and definitely not just for the Jewish community.

As more council minutes, letters, photographs and other documents are found, transcribed and shared, the holes in our understanding of the past and how it has formed the present will be filled. To support or participate in Transcribimus or other Global Civic Society projects, visit globalcivic.org.