Family friends in their 80s just came over to visit. It was perhaps their first time at our house in a year or so. They’ve been busy. They had a family member move back to Winnipeg, there’s been a pandemic and, well, we’ve been busy, too, with kids on summer break, work obligations, visits from relatives, and home renovation.

When they first visited, our new (to us) historic home was empty. While the house had great character, original workmanship and many good points, it also needed a ton of work. We’ve had it all, from asbestos and electricity to plumbing, insulation, and so many other repairs. It didn’t have a single bathroom that worked.

When they walked in today, they said, “Oh wow! It looks like you’re home! It looks like you really live here now.” My kids then took our friends on a grand tour. They were amazed and impressed by all that’s happened. They saw such big improvements and wanted to know what we’d done ourselves, what our contractors had completed, and when and how it had happened. It was wonderfully reassuring, and also strange. We hadn’t realized how long it had been.

I couldn’t pin down when last they’d visited, even though I looked at the calendar. Then I also noticed that it’s Elul, the Jewish month where we’re supposed to wake ourselves up. We hear the shofar each day if going to morning minyan, a way to remind ourselves that Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are coming. We need to look inward, do teshuvah, which is usually translated into English as repentance. Another way of understanding this word is to read it as return.

I have heard sermons or read things that entreat me, as a Jewish person, to start repenting – it’s time to apologize, repair relationships and become a better person. We need the reminder that repairing relationships and apologizing for things we’ve done wrong is important all the time. It’s also a specific ritual to prepare for the High Holidays.

Even as we enter this teshuvah season, I’m thinking of that other definition, the notion of return. Our household has been working hard to cope, in good humour, through an entire year of living through a house under renovation.

We’re lucky – we have a home! It’s mostly been warm and comfortable. Still, we’re all sleeping in temporary places. I’ve had my clothing “organized” in a laundry hamper for the entire year. We’ve had times with one functional bathroom and no kitchen. During this year, there have been days when getting to my chest of drawers or my oven has been an impossibility. We’ve moved and lost things multiple times. We’ve had days without water or heat. Other times, my kids are going to sleep or practising piano or doing homework with contractors working and making noise in the background.

When I see the house through my friends’ eyes, it’s a huge undertaking. This renovation is, in some ways, helping return this home to its best self. When it’s complete, we will have opened up windows and doors that were closed off for 40-some years or more. Things will be safe, full of warmth, light and air, with electricity that’s up to code and even the installation of a much-needed structural beam.

Seeing this house change through my friends’ eyes made me think about this return concept. When we return to ourselves, and hear our inner voice again, it means several things. Our teshuvah/return helps us be the best we can be. First, perhaps we’ve lost our way, but, as the morning liturgy reminds us, we were created in the divine image. It’s like an old house. We have good bones! Maybe we need to do some upkeep, work to stay up to date. Returning to our best selves might require us to listen, pay attention to our gut feelings, do some renovation.

Also, the teshuvah or returning work might be different from year to year. To make a new year a fresh start, we might well have to return to our core values and strengths, open up disused spaces that had been blocked off in ourselves. Sometimes, we start by apologizing to ourselves, too. We all underestimate how far we’ve come and how much we’ve grown and changed. I know our family is guilty of forgetting how much we’ve dealt with over the last year. Although we do remind each other of the changes we’ve experienced, change feels like the only constant right now, as walls move, windows and doors are repaired, and the light comes in again. Through this, we never know which piece of furniture will need moving or what we’ll have to clean (again) because of construction dust.

It’s also about being grateful. Having a kitchen to cook in this summer has been a celebration. How lucky it is to have all this garden produce and to have a place to cook it in. So many don’t have a kitchen or a garden. Maybe they lost it to fire or a bombing. Every day, I feel grateful even as I’m exhausted by my new garden’s potential zucchini and squash crop.

This return work must be grounded in a bigger reality. More than one person has remarked to me that they couldn’t do what we’re doing. In context, though, I’m not sure it’s such a big deal to renovate an old house. People are fleeing wildfires, losing their homes and families, and suffering from war, famine and disease across the world. Living in the middle of a renovation doesn’t feel like too much. It’s a privilege to have a home and have the resources to undertake this repair.

When I’m considering my gut feelings, I know I have high (perhaps unreasonable) expectations of myself and others. I suspect others may approach self-improvement this way, too. Perhaps the biggest teshuvah is remembering that we return to ourselves, while understanding that others might be elsewhere on this path … and that’s OK. Wishing you everything good as we begin 5784!

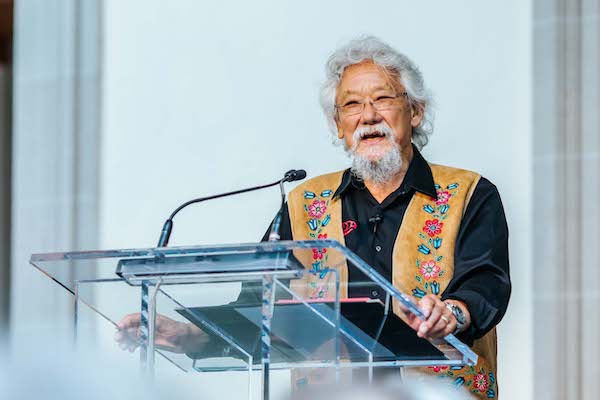

Joanne Seiff has written regularly for CBC Manitoba and various Jewish publications. She is the author of three books, including From the Outside In: Jewish Post Columns 2015-2016, a collection of essays available for digital download or as a paperback from Amazon. Check her out on Instagram @yrnspinner or at joanneseiff.blogspot.com.