Left to right, Talia Martz-Oberlander, Stephanie Glanzmann, Erin Fitz, Mike Houliston and Frances Ramsey wait in Wai Young’s office for a meeting with the MP on July 3, as part of a cross-Canada call for action on climate change. (photo by Sam Harrison)

On July 3, students across Canada visited the offices of seven members of Parliament. “Our asks on that day were twofold,” local participant Talia Martz-Oberlander told the Independent. “Firstly, to have a meeting with our MP and, secondly, to discuss climate policy that would keep Canada’s fossil fuel involvement below seriously harmful levels. To have those two demands met, we were willing to formally sit-in and occupy the offices. Some groups risked arrest, others chose not to.”

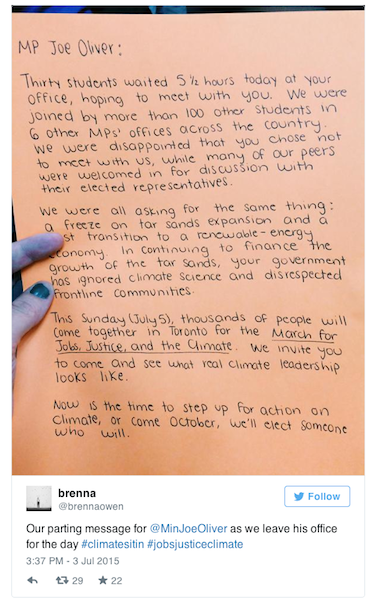

Martz-Oberlander was one of the students who waited in Conservative MP Wai Young’s Vancouver South office for a meeting, to no avail. Actions that day also took place in Victoria (Murray Rankin, NDP MP), Toronto (Joe Oliver, minister of finance and MP for Eglington-Lawrence), Montreal (Thomas Mulcair, leader of the opposition and NDP MP for Outrement), Shédiac, N.B. (Dominic LeBlanc, Liberal MP for Beauséjour), Calgary (Prime Minister Stephen Harper, MP for Calgary-Southwest) and Halifax (Megan Leslie, NDP MP).

Mainly organized by 350.org as part of their We Are Greater than the Tar Sands campaign, cities across Canada held rallies on July 4 “in solidarity with climate-related struggles across Canada, such as the poisoning of water from industries like fracking or open-top mining in rural Canada, the fight for a living wage for Canadian workers, or the continued breach of indigenous territory for extractive purposes,” explained Martz-Oberlander. On July 5, she said, “around 10,000 people gathered in Toronto to march for jobs, social and climate justice, headed by indigenous groups, Canadians living on the frontlines of fossil fuel projects like pipelines, students, workers, elders and every other demographic imaginable.”

Martz-Oberlander said, “The weekend was planned to send a clear message that Canadians want strong climate policy. We are asking for policy that will safely transition Canada’s socioeconomic fabric away from the one-track-minded fossil fuel industry with its large government subsidies towards industry that supports long-term economic prosperity and ecological health, both at home in Canada and globally by being less carbon intensive.”

Entering her third year at Quest University, Martz-Oberlander told the Independent that she has been involved in climate-action work since she was 15 years old. “At that age,” she said, “I didn’t understand the ‘justice’ part of climate change. Through more careful examination of human rights and oppressive social hierarchies like race or gender, I started to realize how closely all social issues are tied with climate change. It is this web of injustice that establishes how most carbon emissions are controlled and released by the richest few and the first stages of the effects of climate change hit the poorest few hardest.”

Homeschooled by her mother until Grade 9, Martz-Oberlander then attended Lord Byng Secondary, initially part-time but then full-time, graduating in 2012. Towards the end of high school, knowing that leaving home to live on her own meant “my religious practice would have to be more intentionally sought out on my part,” she started thinking about how to actively maintain a Jewish lifestyle.

“From a gap year in Boston and a summer learning Yiddish in NYC, I made strong connections in different Jewish circles, including some that identify Judaism with strong social activism,” said Martz-Oberlander. This link “tied together two previously disparate values of mine: Jewish life and supporting long-term life on earth as we know it.”

Before starting university, Martz-Oberlander said she knew she wanted to focus on environmental studies. “However, I’ve always been interested in solar energy alternatives to fossil fuels. This, coupled with a newfound love of physics I found in first year, led me to focus my undergrad research on how we can use electromagnetic radiation, or light, in our design of materials on very small scales. So, my passion for climate justice is fairly macro but I’m asking micro-scale academic questions.

“There is a tiny Jewish community at Quest, although we’re quite active. I and a few others make a point of organizing Shabbatons, celebrations of other Jewish holidays and Jewish discussion group sessions with the belief that existing in the world with a Jewish lens can enrich our lives through finding deeper meaning and practising cultural preservation.

“Of course, I can work on making the world more socially just without acting in a Jewish way, and I often do,” she acknowledged. “However, I strongly believe that living Jewishly is a way of experiencing life that no gentile can truly understand. Outside of religious practices that specifically involve community, such as a minyan or simply having people to spend Shabbos with, there truly is a difference to leading a Jewish life that can impact how one conducts business, studies science, or forms social beliefs and values.”

While her academic studies aren’t currently tied to her climate work, Martz-Oberlander believes that “everyone in any field should be advocating for policy to keep fossil fuels in the ground. After all, it doesn’t matter who burns it – if we keep using known and prospective reserves at our current rate, we won’t be able to sustain ourselves. Internationally recognized scientific findings on these changes can be found in the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] 2014 report on climate change,” she said, before returning to the topic of justice.

“Climate change follows the same cause and effect that social hierarchies implement, so if you keep the ‘justice’ in climate justice, we can make strides in income gaps, which improves society for people of all demographics. With a Jewish lens, one can clearly see the relationship between texts like Deuteronomy or Mishna Bava Batra, which discuss the need to ensure financial holdings are not contrary to others’ well-being, and that industrial toxins are safely managed. A common theme is acting towards tzedeck, justice, when we know what is right and wrong.

“Within issues of fossil fuel use lie many avenues for positive change,” she continued. “These include policy to move subsidies from the industry towards others, such as renewable energies, tourism industries, etc. Another avenue is to input moratoriums on known harmful practices like natural gas fracturing, like Quebec has. Another is divestment from fossil fuels.

“Divestment is by no means a goal, but only a path towards a climate-just future. Currently, we’re caught in this backwards world where we’re investing with the goal of amassing money for the future but we’re doing so by supporting an industry that inherently undermines life to come as we know it.”

One way in which we are doing this is through our mutual funds, said Martz-Oberlander. “Until a few weeks ago, when Vancity released Canada’s first mutual fund that excludes fossil fuel companies, all investment portfolios depended largely upon Canadian fossil fuel companies for their success. This college [or other] fund may grow for a few years but, first of all, finite resources will always eventually be used up and, more importantly, this bank account created to support a child’s future success is ultimately harming this younger generation’s ability to live in an environmentally, economically and socially stable world.”

For Martz-Oberlander, “The science is clear – current, widely accepted climate models dictate that 85% of the Canadian tar sands have to be left in the ground if we are to keep global warming below two degrees Celsius (the target agreed upon by the UN and other international bodies).”

She added that “the divest fossil fuels movement is not meant to financially harm companies. Its success lies in taking away social licence from the fossil fuel industry by waking the public up to the absurdity of investing in something that undermines future human success.”

Martz-Oberlander is one of 10 youth fellows at Fossil Free Faith Canada, an organization that looks at climate justice work from a religious perspective. She found out about the fellowship from a post on the Young Adult Club of Or Shalom Facebook page, she said.

“The post advertised applications for their new Youth Fellowship program, launching late spring of 2015,” she explained. “After the applications closed, the 10 fellows started our work through a weekend of training…. Our mission is to work with faith communities and institutions to support them in divesting from fossil fuels. In this way, our current project is similar to any divestment work, only that we are specifically targeting faith institutions, predominantly larger national or international groups that have endowments or offer pension plans for their members. Without careful financial planning, these investment portfolios almost always include stocks in fossil fuel companies.

“Working in this interfaith setting is quite inspiring because I get to witness how folks of many religions connect to social justice,” she said. “We have diverse approaches to religion and spirituality, but we all share our love of the role faith plays in our lives, coupled with a dedication to what can be really tough climate activism work.

“From my work with Fossil Free Faith, I got in touch with some folks in the U.S. working on divestment from a specifically Jewish perspective…. We’re currently working on forming a supportive network across North America for Jews looking to ask their community institutions to divest from fossil fuel holdings. A brief on Jewish divestment work has been published by a few religious and climate leaders from the U.S. … and, via the use of Skype, a few folks have started a network to support fellow Jews around North America on helping their communities divest.”

In the video that encapsulates the highlights of the 350.org July 3-5 weekend of events, one of the clips has a speaker mentioning the need for “just, rational and difficult choices.” Martz-Oberlander explained that the difficult choices aren’t the ones about “the design or engineering of alternatives. We have used and continue to further refine techniques for using energy from renewable sources, such as the sun, wind or water currents, for many generations. What’s difficult with the energy sector is transferring social and political licences from fossil fuel industries – which, at the rate at which we consume them, are highly destructive not to mention finite – towards energy sources that provide long-term, enjoyable work. That is where divestment comes in.

“Transitioning Canada to a renewable energy nation will mean a change in our economy. Right now, we’re still a raw materials economy, much like we were when this area was first colonized by Europeans, which means we inherently get the short end of the stick – economically and socially. Financially, depending on finite resources is always a losing battle, and Canada needs to get out now. Instead of worrying about changes in global oil supply, we can create financially profitable industries around training engineers to design and run high-tech renewable industries. Which would you rather work – on an oilrig or at a wind farm?”

Martz-Oberlander believes that, “by creating an economy that functions on local industries, such as the service industry, we strengthen communities by keeping jobs where people live and emphasize enjoyable work that provides trickle-down opportunities for multi-generational employment and provision of essential services. One tactic towards this is creating livable cities where life essentials, such as groceries and jobs, can be found close by. This decentralized model is known to increase total employment, which is one of the greatest concerns individuals bring up when I address the issue of reducing fossil fuel industry jobs.”

For anyone wanting to become involved in the type of climate action in which Martz-Oberlander is engaged, she suggested visiting the Fossil Free Faith Canada website (fossilfreefaith.org) for more information. “One great place to start,” she added, “is to get in touch with the board of their synagogue to find out the state of finances there, whether there is an endowment, how finances are handled, etc. There is a growing trend of banks offering socially responsible investment options, so divesting from fossil fuels doesn’t mean reducing profit. I also encourage people in the upcoming federal election to vote for the candidate in their riding whose platform will move Canada away from its dependence on fossil fuels.”

The election on Oct. 19 will be the first in which Martz-Oberlander can vote. “Needless to say, I am very excited,” she said. “However, the novelty of this privilege reminds me of the responsibility that comes with having a say. It is my duty as a Canadian to stand up for the country I want to see all the other 364 days of the year, as well.”