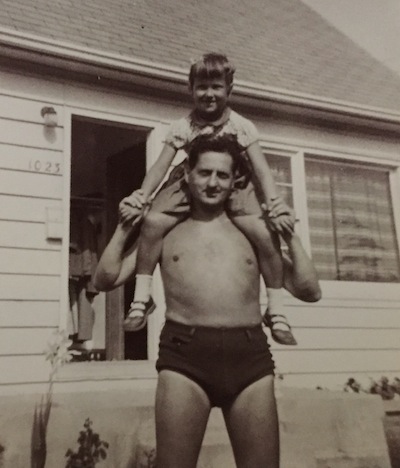

Judy Darcy with her father, Youli. (photo from Judy Darcy)

For years, Judy Darcy’s father carried in his wallet a photo of a little girl. It was one of very few mementoes of the man’s past – a murky history that Darcy and her siblings have only partially reconstructed.

Darcy, the member of the Legislative Assembly for New Westminster, went public with her father’s story on International Holocaust Remembrance Day, tweeting: “… my heart is with my dad who lost family members & kept his Jewishness secret from us to keep us safe.”

The Darcy family had a lot of secrets. Her father had no living relatives and he never spoke of what had happened to them.

“My father’s history was very murky,” she recently told the Independent. “Everything about his family and his relatives was murky and he explained it by saying that he fought in the war and there was a lot of bombing and that he suffered amnesia. I knew he had siblings; I didn’t know any details. I didn’t know how they died. I knew he’d lost track of them. And that he’d lost his memory. It was just grey and murky.”

When Darcy was an infant, the family moved from Europe to Sarnia, Ont., where her father worked in the petrochemical industry. With his wife, he raised a family and progressed in his career. Late in life, after he had retired and been widowed, he moved to Toronto, where his grown children had settled.

“And not long after he moved to Toronto,” Darcy said, “he went to Holy Blossom synagogue and met with Rabbi Gunter Plaut, because he wanted to atone for having abandoned his community.”

Darcy knows nothing of what the conversations between her father and the late, legendary rabbi involved, or whether there was one meeting or a series, but she believes her father took great strength and relief from whatever it was Plaut told him.

Her father began attending the Bernard Betel Centre for Creative Living, a Jewish seniors facility, and formed a companionship with a Jewish woman. But stories of the past came slowly, and not expansively.

“He didn’t sit us down,” Darcy recalled, “it just became part of what he talked about.”

Through snippets of their father’s recollections, shards of history they already knew and the discovery of a recording he made shortly before he died for Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation, the siblings pieced together as complete a story of their family’s past as they are likely to assemble.

Jules (Youli) Simonovich Borunsky was born in 1904 in Lithuania to a Russian-Jewish family. He grew up mostly in Moscow but, in the early 1920s, the family moved to France.

“He always said it was because of the revolution,” Darcy said, “which was partly true, I’m sure, because they owned a factory.” She wonders whether antisemitism also propelled them.

Youli served in the French army, was taken prisoner during the Battle of Dunkirk, in the spring of 1940, and was imprisoned in northern Germany.

“He managed to stay alive in the prisoner-of-war camp because they didn’t find out that he was Jewish,” Darcy said. While a prisoner-of-war, Youli regularly received letters from his wife, Jeanne-Helene, a Catholic Parisienne he had wed before the war.

“She sent him letters every day loaded with Catholicisms,” said Darcy. “And sometimes with little Catholic medals, in order to try to pretend that he was Catholic, not Jewish. Again, I only find all of this out much, much later.”

Through some sort of arrangement facilitated by the International Red Cross (one of many aspects of the story still cloaked in mystery), he was released and made his way back, mostly on foot, to Paris. There, he was reunited with Jeanne-Helene, as well as with his widowed father, Simeon.

Paris was under Nazi occupation and Youli convinced his father that he would be safer going to live with Youli’s sister Rosa, his brother-in-law and their toddler daughter, in Kovno, Lithuania.

Simeon took Youli’s advice. The timing, though, was catastrophic. According to what her father told her, four days after Simeon arrived in Kovno, the Nazis invaded. Pro-Nazi Lithuanians launched pogroms that, later combined with Einsatzgruppen (mobile killing units), murdered almost all of Kovno’s substantial Jewish population. Youli assumed the victims included his father, sister, brother-in-law and the little girl whose photo he would carry in his wallet for years.

Youli had other siblings, Darcy discovered – a sister and brother-in-law who he believed had fled, or were relocated, to Siberia, and another sister about whose fate he had no inkling at all.

“He carried tremendous guilt,” Darcy said of her father. “The guilt of having survived when others died and the guilt of having sent his father to his death.”

Adding to his grief, Jeanne-Helene died of an illness sometime around the end of the war, leaving Youli to care for their son Pierre, Darcy’s half-brother.

After the war, Youli went to extraordinary lengths to hide his Jewish identity from everyone except his wife.

“None of my mother’s relatives knew that he was Jewish,” said Darcy. “Only my mother knew after the war.”

Youli found work as deputy director of a United Nations Refugee Agency displaced persons camp in Germany. There, he met Else Margrethe Rich, a veteran of the Danish resistance who was also working at the camp, and who would become his wife.

They had their children christened in the Russian Orthodox Church in Copenhagen. Their first daughter, Anne Helene, was followed by Judy before the family migrated to Ontario in 1951. Darcy was christened Ida Maria Judith Borunsky – “he threw in a Maria,” Darcy noted wryly – and her younger brother, who was born in Canada, was named George Christian Simeon Borunsky. The obviously Christian names were an active part of the father’s determination to erase his past.

There were the common struggles that immigrant families experience, as well as particular idiosyncrasies. The family home was filled with art and music and books. The family always had enough to eat, but costly red meat wasn’t on the table. Darcy recalled her father’s philosophy: “For the price of a few roast beefs, Judith, you can buy a good painting. For the price of a few steaks, Judith, you can buy a good book.”

When Darcy was 7, Youli took the family to the Lambton county courthouse and changed their surname to Darcy. He wanted something French-sounding, he told them.

What made her father finally open up – to an extent, at least – Darcy can’t be certain. But, in retrospect, there were a couple of hints that only made sense later. A family friend in New York City, who had known Youli in childhood, made a comment to Darcy and her sister during a visit that implied their father was Jewish, then quickly changed the subject when confronted with blank stares.

In Grade 11, when Darcy had an option of studying German or geography, she chose German because, like her parents, she has a facility with languages. Her father hit the ceiling, for reasons she didn’t fathom.

Despite christening his children and giving two of them ostentatiously Christian names, he husbanded a rage at organized religion.

“He would sometimes shake his fist at the sky and say in his heavy Russian accent, ‘If there were a God in heaven, he would not allow the things that happen on this earth,’” Darcy said.

When she moved to Toronto to attend York University, Darcy started hanging out with students who were Jewish.

“When I would go home and I would use some Jewish expressions, my father would completely freak out,” she said, although she knows this only because her mother conveyed the news.

Her father always said that he brought the family to Canada to be safe because there might be another war.

“But, in hindsight,” Darcy speculated, “he did it because he was Jewish and, even though my mother wasn’t Jewish, he wanted to protect us and that’s why he never told us.”

After Youli died in 1997, at age 93, his children found the Shoah Foundation video. The quality of the recording was poor and he was very shaky by then, his memories fading. It contained a few details they hadn’t yet known.

In addition to the video, Darcy and her siblings took notes and recorded parts of their father’s story, but he never shared it from beginning to end. Many pieces remain lost.

“It’s little glimmers of that entire history,” she said.

The photo that Youli carried in his wallet those many years is now framed and sits on Darcy’s shelf at home.

“I don’t know her name,” she says of the cousin she never met, “but her cheeks are like mine and she’s about 4 years old.”