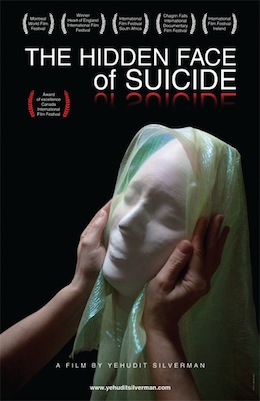

Prof. Yehudit Silverman’s The Hidden Face of Suicide is helping people talk about a topic still surrounded by stigma. (photo from yehuditsilverman.com)

Concordia University professor Yehudit Silverman’s award-winning documentary The Hidden Face of Suicide focuses on the world of survivors – those who have lost loved ones to suicide – and reveals their remarkable stories.

Wanting to learn the story behind the silence in her own family, Silverman offered suicide survivors a creative way to express themselves – using masks. In the documentary, she highlights the danger of secrets and the cost of silence.

Produced and directed by Silverman, The Hidden Face of Suicide features the Montreal group Family Survivors of Suicide. It has screened at Cinema du Parc in Montreal, Curzon Theatre in London, England, on PBS television in the United States, and at various international festivals and theatres. It was also shown at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, as part of the Seeds of Hope project, and is being used in diverse locations in Montreal as an education tool around the issue of suicide.

At Concordia, Silverman leads a graduate program that trains therapists in three different programs – art, drama and music therapies – with the goal of soon adding dance therapy.

The Hidden Face of Suicide, which was released in 2010, came out of a five-year research project about suicide.

“I was interested in the stigma that surrounds it and the fact that it’s not talked about or mentioned,” Silverman told the Independent. “I did a lot of reading about it. Then, I found the Montreal group Family Survivors of Suicide and I met the woman who was the facilitator, named Caroline, and then she invited me to the group.

“I started attending the group and hearing the stories. They all lost family to suicide. I listened and, after I got to know them … I was there for about six months and I wrote down some of the themes that came up, kind of field research – identifying common themes … and a lot of it was having to hide, having people turn away, having to wear a mask.

“And so, out of that, I asked if they would be part of a film. Then, we started working on the film and part of it was them creating masks, since that had come up for them. So, they created masks, wore them and worked with them. And that became a very powerful tool and also a metaphor for those who are left behind.”

Doing this research also spurred Silverman to ask her parents about her uncle’s suicide for the first time. She did so on camera. “I was intrigued with the fact that I had never known about this,” she said. “And, why was that … why was there shame and stigma?”

As well, during high school, Silverman knew fellow students who had taken their own lives – and these suicides, too, were never talked about. She felt compelled to learn more about why that was and to create a film to help break the silence.

While the release of the film and its being so well received was a high point, Silverman also noted an article she wrote reflecting on the whole process – called “Choosing to Enter the Darkness – A Researcher’s Reflection on Working with Suicide Survivors: A Collage of Words and Images” – which was published in Qualitative Research and Psychology.

“I wanted the audience to hear the experience of survivors – what it’s like to be left behind – and to also break the stigma and shame around it. And, it has. People in the audience often stand up and share their own stories for the first time,” she said. “I had a woman in one of my screenings and she said, ‘I’m 84. When I was 24, my mother took her own life and I’ve never talked about it until now. I was too ashamed.’ So, for 60 years she held that in.

“So, that was the goal. I feel like it has been helpful in terms of … breaking the silence. It’s also been used a lot to encourage discussion for people to talk about it, and it’s in universities, libraries and all the suicide organizations.”

Silverman contends that using art to broach such taboo topics allows people to confront issues without feeling overwhelmed. This approach fits with her therapy practice in general, as she uses art as a gateway for patients to share emotions they likely would not share otherwise.

“Talking can often just go around and around in circles, where nothing new is actually being discovered,” she explained. “I’m not saying that always happens. But, I think that using art as another tool can be incredibly powerful.”

Silverman has received positive feedback about the film, including from people who said they were feeling suicidal and that the film helped, as it talked about suicide openly and showed the pain of those left behind.

“I think it can be used to initiate a discussion in a safe way,” said Silverman. “It would be great if someone would use it to create an educational kit…. For me, the emphasis is that, if suicide is still surrounded by shame and stigma, it’s harmful for those who are suicidal. If they feel like people are so ashamed that they can’t even mention it, then how can they reach out for help? So, that’s my message. It feels very sad to me that I made the film in 2010 and I still feel like there’s a lot of stigma around suicide.”

On the other hand, Silverman said she thinks some things are slowly getting better; for example, that clergy are discussing the topic more with their congregations.

“Some rabbis, priests and ministers now mention the word ‘suicide,’” she said. “I’ve been to a few funerals where it’s mentioned very sensitively, but honestly, with, of course, the family’s permission. I think that’s helpful for everyone there, because everyone knows.

“I feel like schools are trying to deal with it in a better way, too. We recently had a suicide at Concordia. I was called in to help with the response. And so, I feel like there is a real desire now to be more honest about it and to try and find the best way, because college kids are very susceptible.”

According to Silverman, suicide is the biggest killer of adolescents and people in their early 20s in Canada, though different cultures and populations experience different rates. The elderly are also vulnerable, due mainly to loneliness.

“With the Inuit population, First Nations, there’s a really high incidence of suicide,” added Silverman. “I’ve gone out north and it’s really sad. They’re also doing some wonderful grassroots stuff to address that.”

Silverman’s film can be rented or purchased online. Visit reelhouse.org/yehuditsilverman/the-hidden-face-of-suicide for more information.

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.