There is an abundance of street art in Bucharest. (photo by Deborah Rubin Fields)

What could be more Israeli than the hora? Well, truth be told, the hora is not Israeli! The word hora comes from Romania. And, like the origins of the hora, the Romanian capital, Bucharest, is a place where the unexpected should be expected.

When you walk along Bucharest’s broad boulevards, one word comes to mind – palatial. There is the former Cantacuzino Palace, today’s George Enescu National Museum; the Elisabeta Palace, the private residence of the former Queen Elizabeth of Greece (born Princess Elisabeta of Romania), following her 1935 divorce from King George II of Greece; the former Royal Palace, today’s National Museum of Arts; the Romanian Athenaeum, today a major concert hall; the Palace of the Deposits and Consignments, still a bank, but today called the CEC Palace; and the Palace of Parliament.

Bucharest once had strong ties to Paris, and French is still mandated in schools. It was called Little Paris, so it should not be a surprise to see that Bucharest’s Manu-Auschnitt Palace is a copy of Paris’s Hôtel Biron (today’s Rodin Museum). While smaller in size, many older private homes were built with stunning stone (perhaps even cement) arches and columns, bas reliefs incorporating figures of lions, men and women, shields, gryphons, eagles, the angel of death, and various free-standing sculptures. In this home, the windows are in national-romantic and neo-Romanian style. Paris-inspired art deco metal work appears on door grills, door overhangs and the tops of buildings. Five classy examples of art deco building in Bucharest are 1 Piata Sfântul Stefan; the Ministry of Justice at 53 Bulevardul Regina Elisabeta; the Telephone Company Building on Calea Victoriei; the “Union” Building on 11 Strada Ion Campineanu; and 44 Calea Calarasilor.

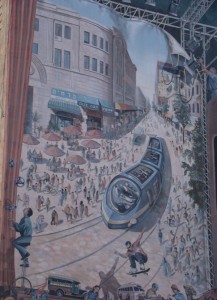

In addition to the number of stunning palaces, there is also an abundance of street art. Some of this street art is commissioned and appears on the sides of various buildings. It is often colourful and imaginative. There is, however, a lot of graffiti, which, apparently, began to appear after the 1989 Romanian revolt against the communist regime. Graffiti is illegal, but, as I was told, the consequences depend on the discretion of who catches the graffiti artist or how fast the artist can run.

Jewish presence in Romania dates to Roman times, when the country was a province called Dacia. The first mention of Jews in Bucharest is from the 16th century. Jews came to Bucharest from two directions: Sephardi Jews came from the south, mainly from the Ottoman Empire; later, Ashkenazi Jews came from the north. The latter, from Galicia or Ukraine, settled in Bucharest after having lived in Moldavia. As in other European countries, Jews were at various times tolerated, even integrated into general city life. At other times, however, they were punished in one way or another.

The Jewish population of Bucharest grew significantly, particularly in the second half of the 19th century. In 1835, some 2,600 Jews lived there; this number jumped to 5,900 in 1860. In the 1800s, nine synagogues were constructed and, by 1900, the total Jewish population had risen to 40,500, making Bucharest by far the largest Jewish community in Romanian territory. By 1930, the city’s Jewish population was 74,480. Jews settled in virtually all the city districts, especially in areas where economic growth was fastest. Bucharest’s Jews laboured as artisans, metalworkers, merchants and bankers.

In the early 19th century, there were several instances in which Jews were accused of ritual murder. This led to violence and pogroms. While, on the books, Jews were to be given citizenship, government after government dragged its feet in making emancipation stick. In general, being Christian was a prerequisite for Romanian citizenship, although a complex naturalization process was theoretically made available to Jews. When, in 1866, Jewish French lawyer Adolph Crémieux came to Bucharest to help push for Jewish political emancipation, rioters attacked Jewish shops and synagogues. Toward the end of the century, many antisemitic organizations existed, due in large part to nationalist leader Alexandru C. Cuza’s political activities. In particular, his followers organized antisemitic agitation against Jewish students at Bucharest University.

After Germany, Romania is directly responsible for more Jewish deaths in the Shoah than any other country. For most of the Second World War, Romania allied with Nazi Germany. According to official Romanian statistics, between 280,000 and 380,000 Jews were murdered or died in territories under Romanian administration during the war. Antisemitic legislation downgraded the identity of Jewish citizens to second-rate status: they lost the rights to education and health care, their property was confiscated, and they were forced to perform hard labour. In September 1942, approximately 1,000 Jews were deported to Transnistria.

Despite such treatment, most of Bucharest’s large Jewish community was spared the worst horrors of the Holocaust. Between 1941 and 1943, Bucharest-based Chilean charge d’affaires Samuel del Campo saved the lives of more than 1,200 Romanian and Polish Jews by issuing them Chilean passports, thus preventing their deportation to Nazi concentration camps. A memorial stands in front of the former Ashkenazi Great Synagogue, commemorating the January 1941 paramilitary Iron Guard’s (Legionnaires’) savage murder of 125 Bucharest Jews, an action reminiscent of Nazi techniques, with the skinning of the victims and the hanging of them on meat hooks.

Shortly after the Second World War, Bucharest experienced a great influx of Jews, as refugees arrived from concentration camps and from several areas in Romania where they continued to feel unsafe. By 1947, the Jewish population had grown to 150,000.

After the first years of the communist regime and the closing of Jewish welfare and religious institutions, Bucharest continued to be a centre of Jewish communal and cultural life due, in large part, to Chief Rabbi Moses Rosen, who coped with the inconsistencies and peculiarities of Romanian official policy – particularly during the 1965-1989 dictatorship of Nicolae Ceausescu. When former US ambassador Alfred Moses first visited Bucharest in 1976, a young Jew approached him saying, “Don’t believe what they tell you. The situation here is terrible, especially for Jews. We are blamed for everything that goes wrong. Help us get out. There is no future for Jews in Romania. Everything you hear is a lie, a lie, a lie.”

After the rebirth of the state of Israel, many Jews made aliyah. By 2000, only 3,500 Jews were left in Bucharest. Today’s Jewish life in Bucharest focuses on three synagogues, a community centre, a kosher restaurant and the Centre for the Study of the History of Romanian Jews.

In 2021, a Romanian survey reported one-fourth of respondents saying they didn’t know or couldn’t say exactly what the Holocaust was. Another 35% said they couldn’t identify the Holocaust’s significance for Romania. In 2022, the populist Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR) opposition party called Holocaust education a “minor topic” when it was mandated in Romanian high schools. This party currently holds 12% of parliament seats and some people predict it will become a major political force in the near future.

On a more positive note, a few years after the death of Jewish Romanian Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel, at age 87, Bucharest memorialized him with a bust in the Piata Elie Wiesel.

Finally, if you hear what sounds like a Slavic language spoken in Bucharest, it might just be Ukrainian. Since Russia began its attack on Ukraine two years ago, 11,000 Ukrainian men of conscription age have illegally fled to Romania. It is too early to say how this population will impact Bucharest life.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.