“The Valley of the Shadow” by Michal Tkachenko.

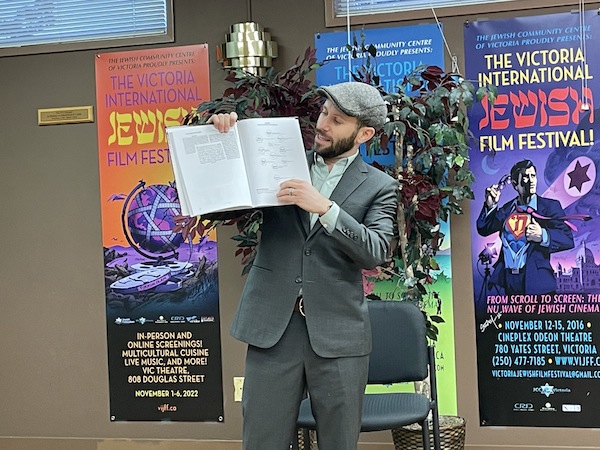

Songs of Deliverance, a solo exhibit by Michal Tkachenko, opened last month at the Zack Gallery and is on display until Nov. 10. While its title is inspired by the lyrics of a Bethel Music song – “You unravel me, with a melody / You surround me with a song / Of deliverance, from my enemies / Till all my fears are gone” – its focus derives from three psalms.

“I really wanted to have a subject for the exhibition that would bind communities together and so I came to rest on the psalms, which span both Judaism and Christianity, but are also used in secular society as a means to reach out to a greater being beyond ourselves,” Tkachenko told the Independent. “For me, this is a huge departure from previous work in both subject and vulnerability. It is my most honest work so far and, as the exhibition falls on the two-year anniversary of everything I saw with my spirit, I feel myself rising from the anguish and am ready to speak about my experience now, to move towards creating what I saw was possible.”

Lacking the exact words to describe it, Tkachenko said she had a near-death, or mystical, experience two years ago, and she was in that state for more than a week.

“It instantly changed my entire outlook on life and death and it completely changed me,” she said. “I was so excited about it until I began to realize how isolated it made me and how those I reached out to didn’t always have a helpful response. I quickly spiraled into the dark night of the soul and have been traveling that road…. Two very deep things came to rest in me during this time. The first was a deep longing in my spirit for something greater than myself, to draw and stay extremely close to God. The second was a deep grief that all that I had seen with my spirit, particularly an unseen solid force of love that is everywhere and how we are meant to love and be vulnerable with each other as our primary purpose in life, were things I could not make happen however hard I tried.”

Psalm 23 – “As I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil” – was with Tkachenko throughout this two-year period. “For me,” she said, “it was a psalm about my journey and how, in the midst of the darkness, God was always with me and more vivid than I had ever experienced outside of that extraordinary week.”

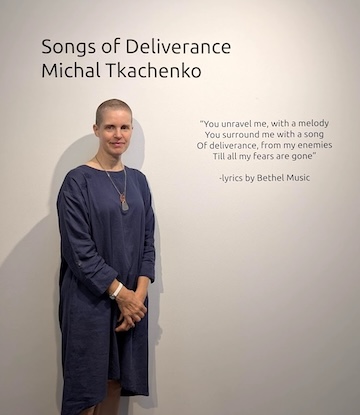

As she approached the one-year anniversary of that week, Tkachenko asked two people to write her a blessing, as she made a vow to God and shaved her head. “One of the blessings,” she said, “included Psalm 63 and it reflected my own deep longing for God, ‘I thirst for you, my whole being longs for you, in a dry parched land where there is no water.’… My hair that I shaved off is part of the exhibition in an aged box that is meant to suggest a holy relic of the past, when people had more vivid experiences with God.

“Psalm 139 is such a beautiful expression of God’s love and absolutely full of beautiful imagery as an artist,” she continued. “It is a psalm that has also kept me company on my two-year journey and moves me every time I read it.

“For this psalm,” she said, “I made a pile of sketches of different verses and the images that came to me. Of those, I chose seven to do larger pieces on mylar. In many of the pieces, the spirit of God is represented by the white negative space. In ‘You Hem Me in Behind and Before, You Lay Your Hand Upon Me,’ the image of a human is abstracted in a long, dark column down the centre of the page, but the figure is not the focus. Instead, the white empty space is the representation of God hemming that figure in from ‘behind and before.’”

Songs of Deliverance marks Tkachenko’s return to drawing and painting after this two-year period, during which she spent a lot of time writing. “My goal is to make short, layered videos using these writings,” she said.

She also took a break from painting during COVID, making art out of dollhouses that people were getting rid of in the decluttering that took place then. In these dollhouses, she created COVID lockdown scenes in miniature.

“My interest is not held by one medium or one style alone, although I do have a style that often emerges naturally,” she said. “The older I get, the less interested I am in creating what I think others will like or want to buy and more about what I want to say and what I am excited about making and expressing through the medium that seems best suited to that particular message.”

Tkachenko was born in Victoria but grew up in Vancouver. Her dad, an architectural technician, builder and musician, was a Ukrainian immigrant to Canada after the Second World War, while her mom, a teacher, music teacher and musician, was a second-generation Canadian with a Scottish/British background.

“My parents were part of the hippy movement in the ’60s and ’70s and, when I was young, we lived in communal housing,” said Tkachenko, who is the oldest of four sisters.

“Growing up in a big creative household, there were always guests and cooking parties (Ukrainian food), live music and all sorts of art projects going on,” she said. “My parents didn’t push the academics as much because they wanted to make sure we found what gave us excitement and joy and they invested in building our self-esteem instead.”

That said, Tkachenko has a bachelor’s and a master’s in fine arts. For her schooling, she has lived in Vancouver, Victoria, Calgary, Toronto, Florence and London (England). She has lived and volunteered in Haiti, Kenya, Malawi and Liberia, among other places. She has studios in both Vancouver and Manchester, as she, her husband and kids travel between Canada and the United Kingdom.

Despite knowing from a young age that she was going to be an artist, it took time for Tkachenko to recognize her skill and justify making art – “I considered it a luxury item, when the poor existed in the world,” she said.

“My hippy parents had driven us down to Mexico a number of times when my sister and I were young children (we are the oldest two) and we had been taken to the slums to understand how most of the world lived and how, despite our modest life in Canada, we were rich compared to rest of the world. It had made a huge and lasting impression on me as a child.”

At 18, she moved to Haiti to volunteer for a year, she said, “but before the year was out, I was in a life-altering car accident in which a friend died, my skull was shattered and my face smashed in on one side. I was flown back to Canada for reconstructive surgery and to recover.”

She volunteered for a spell in Kenya a few years later, but then finally decided to follow her calling in art.

Tkachenko works out of Parker Studios in Vancouver. She is also on the advisory committee for the DTES Small Arts Grant. “Being on this committee and working out of Carnegie [Community Centre] in the Downtown Eastside joins two things I value – the arts and working among the less fortunate,” she said.

Tkachenko’s husband is Jewish on his mother’s side – “her parents fled Czechoslovakia and Germany for the UK during WWII,” Tkachenko shared.

“Although they purposefully lost a lot of their Jewish heritage during the shift for safety reasons, my kids and I have become interested in it,” she said. “I came from a very open faith background because my parents were hippies that were part of the Jesus People Movement. They always encouraged us to find our own way to God and faith and, as a result, the people I am drawn to with my spirit are varied, from Jewish to Muslim, from Buddhist to Eastern Awakenings. The value of community does go beyond a single group [an idea she explores in one of The Journey series videos she is currently working on] and the more open and loving we become with each other, the more we can appreciate the differences that we each were gifted. And the more we see the bigger picture and what we all have in common.”