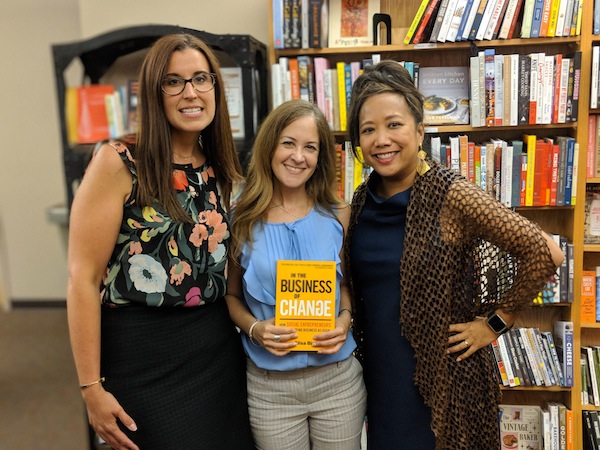

Elisa Birnbaum, centre, with Laura Zumdahl of Bright Endeavors, left, and Maria Kim of Cara Chicago. (photo from Elisa Birnbaum)

Toronto-based Elisa Birnbaum, editor-in-chief of SEE Change magazine, aims to inspire and give hope in many ways. Her book In the Business of Change: How Social Entrepreneurs are Disrupting Business (New Society Publishers, 2018) is but one of those ways.

“I’m a lawyer by training, but was always a writer on the side, enjoying writing and storytelling,” said Birnbaum, who was born and raised in Montreal in an Orthodox Jewish family. “I decided to try writing out for a little bit and to go back to law after. That was 15 years ago. I never went back to it.

“I was writing a lot about the nonprofit and charitable sector in Canada, as well as in the U.S., and I was also writing a lot about business, a strong interest of mine, too. I noticed how there was a melding of the two – how a lot of challenges in the nonprofit and charitable sector … how they could be helped through business and through business savvy…. So, when I saw what social enterprise was all about and how it was using business to solve social challenges, I realized the importance of that. I became really intrigued and interested. It was an area that, I thought, ‘Hey, this is something I really want to explore further.’”

Birnbaum started pitching stories about social enterprises to any editor who would listen. While some of her work went out via mainstream media, Birnbaum felt more was needed, so she co-founded SEE Change, which is devoted to telling the stories of social and environmental enterprises.

“I thought they symbolized a new way at looking at business,” she told the Independent. “I really felt this was the future, with how we work with business and how communities can tackle social challenges through business, and these types of savvy-ness and skills.”

After years of publishing the magazine, Birnbaum wanted to put together a book of such stories, both to delve more deeply into the phenomenon and, hopefully, to inspire and teach readers how to take on the task of starting a social enterprise.

“A lot of times, I’d get some young people or even older people who were interested in social entrepreneurship themselves, and they’d like advice and tips, and were constantly looking for more information from anyone who’d done it before,” she said. “So, I thought, I could also provide lessons learned, tips, advice and resources … so, a bit of storytelling, as well as a resource for those who are starting up or looking to start their own.”

As far as the response to the book so far, Birnbaum said she has been asked by schools and organizations to speak about the topic. “There were people who had never heard about it before and are now really inspired by the storytelling, which is great,” she said. “There are other people…. I was at a couple of universities recently, and some students there said they picked up the book and were now interested in starting their own social enterprise.”

According to Birnbaum, a very broad definition of a social enterprise is a business, whether nonprofit or for-profit, that has a social or environmental mission at its core, as opposed to a business that has profitability and sustainability at its core. The unique aspect of social entrepreneurship, she said, is that it approaches business in a new way.

In her book, Birnbaum makes a point of highlighting a large array of social enterprises from around the world, including a few in British Columbia. For example, Saul Brown’s Saul Good Gift Co. (itsaulgood.com) creates gift boxes filled with locally made artisan food that people can give their loved ones across Canada, and Reena Lazar’s Willow (willoweol.com) helps with end-of-life planning.

Marc Schutzbank, director of Fresh Roots (freshroots.ca), grew up in the United States and moved to Vancouver to finish his education at the University of British Columbia 10 years ago on a Fulbright scholarship, looking at the economic viability of urban farming. This line of study led him to an organization called Plant to Plate, in Pittsburgh, Penn., where he attended University of Pittsburgh.

“As part of my research, I was looking at urban farms in Vancouver – if they were growing, how much food they grow, who they’re sharing it with,” Schutzbank told the Independent. “I have a finance degree, so I was looking at if they were making any money. As I was doing that, there were a couple of people who were doing work in the social space. So the goal wasn’t to grow and sell food; the goal was to share it or to reduce barriers to employment. And so, as I was getting to know them, Fresh Roots was moving from backyards into school grounds.”

One particular backyard caught Schutzbank’s attention. He wanted to know how much food was being grown in such a small space. He discovered, to his amazement, that this one backyard could feed three families. As they expanded to eight backyards, they could feed 35 families.

One of those backyards was adjacent to an inner-city elementary school with a rundown garden plot. The school invited Fresh Roots to develop the plot. As they did, the students, teachers and parents became increasingly interested. The teachers began using the garden as part of their curriculum, as a place to build learning capacity.

“It turns out that, when kids are outside growing food, their academic confidence increases,” said Schutzbank. “They are able to find some success, and this is often in places with kids that are having a hard time finding success inside the classroom [in straight rows]…. Learning like that doesn’t work for everyone.”

Another benefit of this was that bullying decreased at the school, as kids had a positive physical outlet. As well, Schutzbank found that, as the saying goes, “If you grow it, you eat it.”

Other schools picked up on what was happening and asked Fresh Roots to do the same at their schools. Fresh Roots is now at four high schools and one elementary school.

Fresh Roots also started a salad bar program for students – twice a week, all of the students get to eat the produce from the garden.

“In Canada, we are the only G7 nation that doesn’t have a federal meal program,” explained Schutzbank. “It’s a bit crazy that Canada doesn’t have that. All those kids without lunches are hungry, regardless of how much food is at home. It’s really critical for learning, to have food…. So, at Fresh Roots, our vision is good food for all – so everybody has access to healthy land, food and community.”

In addition to the food they grow, Fresh Roots supports and encourages teachers to have classes outside in the garden. “They need to touch, taste and feel,” said Schutzbank of the students. “Those are really critical parts of our senses and a really important way of learning.”

As well, Fresh Roots provides employment – especially in the summer – for youth who are struggling.

Schutzbank said you can’t grow food without eating and sharing it, so Fresh Roots’ philosophy is “around sharing all the food back through the programs and everything we are doing.”

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.