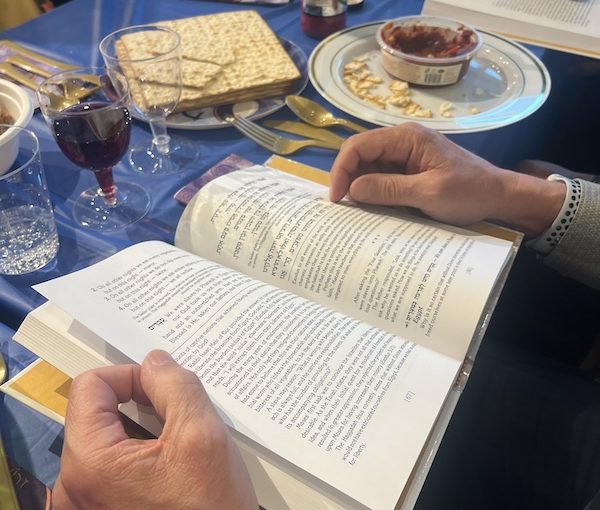

Held on April 15, the Third Seder: Understanding Addiction and the Path to Freedom focused on the slavery of addiction. (photo from JFS Vancouver)

There was matzah, grape juice, charoset and horseradish on the table. Guests read from the Haggadah and enjoyed a meal of matzah ball soup, brisket and roasted vegetables. At first glance, you might think this was just another seder – but it truly was different from all other seder nights.

The Third Seder: Understanding Addiction and the Path to Freedom was held April 15, with Rabbi Joshua Corber, director of Jewish Addiction Community Services (JACS) Vancouver, at the helm. All the guests had something in common: they were people with or recovering from addiction, or family members of loved ones who have experienced or are still struggling with addiction.

“No situation is more similar to slavery than one’s addiction. Someone who has experienced addiction truly understands what it means to be a slave,” said Corber as he introduced guests to From Bondage to Freedom: A Haggadah with a Commentary Illuminating the Liberation of the Spirit, written by Rabbi Dr. Abraham Twerski (1930-2021).

“Rabbi Twerski, z”l, is an absolute giant,” Corber explained. “Steeped in Torah learning and Chassidus, he was a psychiatrist who specialized in addiction and, with this background, his ability to leverage Torah as a recovery tool is unparalleled. This is reflected in his Haggadah, but he also led the way for other Torah scholars.”

At all other seders, guests drink wine or grape juice, but at the Third Seder, only grape juice was on the table. Guests recited sections from the Haggadah that wrestled with concepts like liberation from addiction, and how family members could deliver “tough love” by setting boundaries. They expressed their pain and shared their stories with candour.

“Slaves to addiction tend to think recovery isn’t possible,” said one guest, who introduced himself as a recovered alcoholic.

Corber agreed. “I thought addiction was my life, and that I needed to tolerate it,” he confessed. “I was held down by inertia because addiction was the only life I could imagine. In some ways, it was like I was already dead.”

The guests at the seder, which was held at Reuben’s Deli by Omnitsky, ranged in age from 22 to 80. Some were still wrestling with active addiction, while others had been in recovery for lengthy periods. Together, they formed a community of support that was inclusive and devoid of judgment.

“Addiction is a family disease and having a community for recovery is amazing,” one guest declared.

Corber echoed those sentiments. “A goal of JACS is to get the whole community behind the cause of supporting Jews entering recovery or coming out of addiction and, so far, that’s been missing,” he said.

There remains a stigma surrounding addiction, particularly in the Jewish community, Corber said. “There seems to be a reluctance to discuss the matter openly in the community and we have to break this stigma. Addiction is not a choice, it’s a disease. And, while most of us acknowledge this, it has not fundamentally changed our attitudes. Jews who are struggling need to feel supported and accepted by their Jewish community.”

Corber said the Third Seder will become an annual event, and more programming is being planned for Shavuot and other Jewish holidays. For more information, visit jacsvancouver.com.

Lauren Kramer, an award-winning writer and editor, lives in Richmond.