Left to right are Canadian Friends of the Hebrew University Vancouver president Stav Adler, CFHU Vancouver executive director Dina Wachtel and Hebrew U’s Prof. Yoram Yovell. (photo from CFHU Vancouver)

The happiest time in the average person’s life is when the last grown child leaves home and the dog dies. That was the tip of the iceberg in happiness advice from one of world’s foremost experts and researchers on the subject.

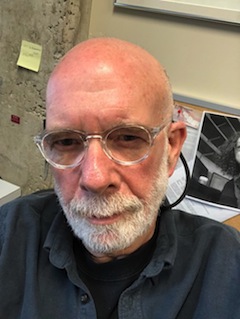

Prof. Yoram Yovell, a psychiatrist, brain researcher, psychoanalyst, author and media phenomenon in Israel, spoke to an overflow crowd at Beth Israel Synagogue July 25. An associate professor in the division of clinical neuroscience, Hadassah Ein Kerem Medical Center, at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Yovell is author of two bestsellers: Brainstorm and What is Love? He hosted the award-winning primetime TV show Sihat Nefesh (Heart-to-heart Talk) for 10 years. His visit was presented by Canadian Friends of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and made possible by the Dr. Robert Rogow and Dr. Sally Rogow Memorial Endowment Fund in Support of Academic Lectures.

Yovell speculated that the audience was so large because of a sad fact about Vancouver.

“Now I understand why all of you are here,” he said. “I didn’t know this before I came here – you are considered to be the unhappiest city in Canada.”

He supposes this status might have to do with the combination of rainy days and the proportion of new Canadians, because “immigrants, for very important reasons, happen to be less happy than people who live in the same place where they were born,” he said.

But advancing happiness (or ameliorating unhappiness) requires us to define it, he said. He asked the audience to raise their hands if they were happy – most did – but then he demanded to know how they knew they were happy.

“That question sounds silly,” he said. “Because happiness is a subjective mental state. It’s something that I feel inside.… You probably did with yourself something that you would have done had I asked you, are you hungry or not hungry? Are you hot or cold? Are you tired or awake? In all the circumstances, people look inside and try to get a certain feeling and then that’s what they report. By doing so, we are treating happiness as if it’s something we feel. I’m not saying it’s bad that happiness is something we feel, but I think we have lots to gain by really questioning whether happiness is something that we feel or something that we do.”

Aristotle, who wrote a lot about happiness, differentiated hedonia, pleasure, from eudaimonia, a much more complex concept that has more to do with achieving one’s potential in every aspect of our lives.

Instead of asking, “Are you happy?” Aristotle would ask, “Are you the best doctor you can be, the best husband, the best parent?”

Yovell said, “And, if the answer is yes, or almost yes, to most of those questions, then, for Aristotle, I’m eudaimonia and he doesn’t care how I feel.”

Tal Ben Shahar, an Israeli who wrote the book Happier about 2,400 years after Aristotle’s ponderings on happiness, developed a simple equation: happiness equals pleasure plus meaning. This dictum is, Yovell said, the only thing that every school of philosophy and every religion agrees on. Pleasure does not equal happiness. Meaning is the additional ingredient that turns fleeting pleasure into lasting happiness.

“The contribution of pleasure to happiness is there, but it’s small,” said Yovell. “And what’s even more important is it does not last, whereas the contribution of meaning to our happiness is huge and it’s stable. That makes an enormous difference to how we should conduct our lives if we want to be happier.”

One example he discussed was a study showing that most parents say, in retrospect, that child-rearing is the thing that made them happiest. But ask them when they’re changing diapers, doing laundry or settling squabbles, and they’ll tell you their happiness level is in the basement.

“It doesn’t really matter what you felt in the meantime,” he said. “What matters is what is kept in your memories. We live in our memories.”

Having children, for most people, is the most meaningful thing they’ve ever done, said Yovell.

“Pleasure is good. Have a good dinner, have a vacation abroad, upgrade your car model – all these things are going to make you happier. But not to a great degree and not for very long,” he said. “The things that are going to make us happy long-term are the things that give our lives meaning.”

Still, the road to happiness can be arduous.

“If you take a regular couple and ask, ‘When are these two people going to be at the top of their marital happiness?’ the answer is a short time after they get married and, with every child they have, their level of happiness decreases. And when their first child hits adolescence …” at this point his words were drowned out by the laughter and applause of the audience. “You know what I’m talking about, right?” he said.

“But there is light at the end of the tunnel,” he continued. “For those of us who manage to bypass this ‘Death Valley,’ there is going to come a time in our marital life where our happiness level [improves]. The vast majority of you are going to get happier … the older you become, the happier you’re going to be.”

A study of 340,000 American men and women looked at the correlation between their well-being and their age.

“At 18, they’re pretty happy – before they’ve realized what’s going to happen,” said Yovell. “Soon, they go off to college and there goes their happiness and they keep going down and down and down and it gets worse and worse and then they hit rock bottom here, in the 40s and 50s,” he said, pointing at a slide on the projection screen. “But, it gets better as they get older, sicker, less attractive, closer to death – and happier.”

Yovell’s academic work has often focused on reducing extreme unhappiness so that, for example, suicidal people are improved enough to be brought back from that brink.

He cited Sigmund Freud, a founding board member of Hebrew University, noting that “many things that Freud hypothesized were proven wrong, but many were proven right.” One example, he said, was Freud’s observation in his first book that “Much will be gained if we succeed in transforming hysterical misery into common unhappiness.”

The science of happiness has advanced dramatically in just the past two decades, Yovell said. We now know that the parts of the brain that register physical pain overlap with those that register emotional pain.

“This is something that 20 years ago we knew absolutely nothing about and now we do. In the last two decades, we’ve gradually learned that it is true that mental suffering is encoded in our brains using the same neural pathways, the same neurotransmitters that also mediate the extremes of physical pain.”

If you ask a friend about the most painful thing they’ve experienced in their life, they are unlikely to tell you about a ski accident or an operation, he said.

“They’re going to tell you about the loss of a first-degree relative. They’re going to tell you of how they felt when a father, a mother, a sibling, a spouse or, God forbid, a child has died and has left them bereaved,” said Yovell. “That, for most of us, is going to be the most painful thing in our life.”

Similarly new research indicates that emotional pain is something we can quantify, that it is more than subjective. With this knowledge, Yovell said, the follow-up question is: “Can we make it better and, if so, how?”

First, it is important to understand what we can control and what we cannot.

In 2014, a study looked at the relationship between happiness and genetics and concluded, the professor said, “that our genetics do influence our happiness but they are responsible for about 32% of our happiness, which means that 68% of our happiness – more than two-thirds of how happy or unhappy we’re going to be – has something to do with us. Part of it is the circumstance into which you were born, but the rest is how we conduct our lives – both our real lives out in the world and our inner world, our mental lives. This is what we have to work with and that ain’t bad.”

Yovell described a study of university students, in which a control group was given a placebo and another group regular-strength Tylenol and participants were then asked to journal about how they felt with their ongoing lives on campus.

“Those who got Tylenol instead of placebo actually experienced those mental pains to a lesser degree,” he said. “That’s nice, but that ain’t going to do the job when things get more difficult when someone, God forbid, loses a spouse or when someone sinks into a big depression. Tylenol will not be the answer. But what about opioids? What about narcotics? What about those drugs that mitigate the effects of endorphins. Do they make mental suffering better? And, if so, at what price?”

Opioids were used in the treatment of depression for at least 100 years, he said, between the mid-19th and mid-20th centuries.

“Drugs like morphine and codeine were the first drugs of choice in the treatment of mental depression and they actually worked,” he said. But the problems were threefold. These drugs induce tolerance, meaning a patient has to increase the dose in order to achieve the same effect. Narcotics or opioids also cause addiction and that’s a huge problem. And they are easy to overdose on.

Recently, scientists have begun investigating the use of the opioid buprenorphine.

“It’s less addictive and it’s much less dangerous in overdose because, if you give it in high doses, it actually blocks its own effect, so it’s very, very hard to overdose on,” Yovell said. “Even though it’s 40 times more potent than morphine, it’s actually a lot less dangerous to overdose and also less addictive.… We took people in Israel who are not only incredibly depressed but also suicidal. In addition to existing treatments for their depression and suicidality, the experiment added buprenorphine to their regimen.… Those who received the active drug, unbeknownst to them and to us as well, continued to improve. So there is hope, which is very nice.”

A drug-free way to marginally increase one’s happiness, he said, is simple goodness, generosity and philanthropy. Making others happy makes us happy, he said.

“People who contribute their time and money, who volunteer, will not only be happier, they will live longer,” he said. He then directed audience members to donation forms on their tables and asked them to consider contributing to scholarships for graduate students who are working with him.

“I leave it up to you,” he said, “whether you want to save your lives.”