Judith Weiszmann holds an audience of students spellbound at Merivale High School in Ottawa in October 2013. (photo by Jeremy Page)

No matter the audience, Judith Weiszmann has three key messages when she speaks about the Holocaust: always remember the good that one person can do in the world, pay attention to the pockets of antisemitism springing up in some parts of Europe and North America, and remember that living in peace with your neighbors is much better than the alternative.

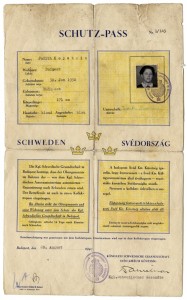

Judith and her husband Erwin, z”l, both structural engineers who emigrated to Canada after the Hungarian Revolution, were frequent speakers about the Holocaust for schools and service clubs in Winnipeg, where Judith still lives and continues to be an outreach speaker. The families of both Judith and Erwin were saved by Raoul Wallenberg, the Swedish businessman-turned-diplomat who came to Hungary towards the end of the war and managed to issue thousands of Schutzpasses (a document identifying the bearer as a Swedish citizen rather than as a Jew) to Hungarian Jews who were on the brink of being deported to concentration camps.

In 2011, the Swedish government issued a stamp commemorating the 100th birthday of Wallenberg. It featured a picture of Wallenberg in the foreground and an image of a Schutzpass in the background, complete with a picture of the 14-year-old bearer of the pass, Judith Kopstein, who later became Judith Weiszmann. Serendipitously, Judith had presented a copy of her Schutzpass to Wallenberg’s half-sister Nina 10 years previously when Nina attended the unveiling of a statue in her brother’s honor in Toronto. Upon returning to Sweden, unbeknown to Judith, Nina framed her Schutzpass and hung it in her home. Years later, the Swedish Postal Services made use of the image and Canada also issued a stamp using the same Schutzpass, never imagining that the young girl pictured in it was still alive. When Canada Post learned that Judith, then 83, was very much alive, and tremendously honored to appear on a Canadian stamp with Wallenberg, they held a special ceremony for her in Toronto to mark the connections.

Since the issuing of the Wallenberg stamps, Judith has received a wide-ranging number of speaking requests – requests she is only too glad to oblige. In her words, they provide her with an opportunity to “bear witness” to the selflessness of Wallenberg and remind her audiences that forces of evil can take root again if we are not vigilant.

In Ottawa, in October 2013, Judith held an audience of students spellbound in the ethnically diverse Merivale High School during both her morning and afternoon presentations. According to teacher Irv Osterer, whose efforts resulted in Judith’s visit, “by the afternoon, word had gone around the school about how important it was for everyone to hear this woman speak. By the afternoon presentation, the kids were almost hanging from the rafters of the auditorium.”

Drawing parallels between the fact that she was the age of many of the high school students when she lived through the Holocaust, she inspired the students with messages about the difference one person can make in the world, how hating your neighbor is not a way forward, and about how a better world will come from all of us living side by side in peace. At the conclusion of her remarks, a young woman in a hijab bounded to the front of the theatre to give Judith a spontaneous embrace.

From Ottawa, Judith continued to Toronto, where she spoke to a joint session of B’nai Brith Canada and the Law Society of Upper Canada and to a conference hosted by Canada, the 2013 chair of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA), an international body that deals with Holocaust and related educational matters and liaises with several governments, Holocaust researchers and educators.

As a result of the Toronto speaking engagements, in February 2014, Judith had the opportunity to realize a lifelong dream, which was to travel to Wallenberg’s homeland, Sweden. On this occasion, she was the guest of the Canadian government and was asked to speak once more to another conference of the IHRA in which the leadership of the alliance rotated from Canada to England.

The stories she told of how the war affected Hungarian Jews and how Wallenberg’s interventions saved thousands of Jews from the gas chambers no doubt resonated as deeply with the Swedish audience as they did with those in Canada. One of Judith’s most remarkable memories is about the last time anyone in the West actually saw Wallenberg.

Judith’s father, Andor Kopstein, was a senior administrative support to Wallenberg. German was the language in which they communicated. On the final day Wallenberg was seen, they were in Budapest together, as Wallenberg was to travel to Debrecen, a Hungarian city that had already been liberated. In conjunction with the Swedish Red Cross, Wallenberg’s intentions were to purchase food in Debrecen for the general population in Budapest, all of whom had had little access to food. It was widely known that Wallenberg had a considerable amount of gold on his person – funds provided by his own government and the governments of several Allied countries – with which he planned to pay for the food. Wallenberg was about to get into the middle car of a three-car convoy, with Russian military officers in the lead and last cars. Just before the convoy pulled away, Wallenberg said to Judith’s father, in German, “I am not sure if these are my bodyguards or my captors.” Wallenberg was never seen again. A young Judith had watched the exchange, hiding behind an entrance door to her apartment building, and her father repeated Wallenberg’s words to her when the convoy departed.

At the conclusion of the IHRA conference, Judith met with several Hungarian men and women who had moved to Sweden immediately after the war. At the end of the war, Sweden offered the opportunity for Jewish orphans to be brought to its shores. All those who came at that time have remained in Sweden and made their lives there. Other Hungarians came to Sweden after the Hungarian Revolution in 1956.

Judith gave one further presentation on her trip: to teachers involved in an educational institution that the Swedish government formed some years ago after hearing about resurgences of antisemitism in Norway and elsewhere in Europe.

The fate of Wallenberg has never been known for certain but was undoubtedly a topic of conversation when Judith had the chance once more to meet his half-sister Nina. Stopping for tea with Nina and several of Nina’s nieces, and with her own daughter Ann, who accompanied her on the trip, Judith told one interviewer that she and Nina were “united in a love for her brother Raoul.”

From Sweden, Judith traveled to Budapest to visit with relatives and speak at the Jewish Club, a sort of unofficial arm of the IHRA. The club receives some modest financial help from the alliance for its efforts to fight antisemitism. Its main activity is to present lectures and other educational presentations to teachers, students and, occasionally, the general public about the Holocaust and antisemitism. As Judith explained to me, “During the communist regime, there was no education about WWII. Today’s reality is that there is whole generation of teachers who have grown up with no background whatsoever on what happened during the war, Hungary’s role in it and the consequences of antisemitism. They cannot teach what they do not themselves know about.”

Judith’s presentation drew about 70 people, 60 of whom were students at the senior high school or university level. Organizers told her that about 55 of the students present were non-Jews, which Judith saw as an expression of interest and open-mindedness, and she remarked that the students asked intelligent questions. Many attendees admitted that they were hearing for the first time about Hungary’s role in the war and about the treatment of Jews and other minorities during that time. At the conclusion of her talk, one non-Jewish young man stood to say that he knew that there were fewer survivors each year and that “we young people have to take over and talk about it.”

Since returning home from Sweden and Hungary, Judith continues to share her messages with groups of students and others in Winnipeg. Now, she also wants to talk about new concerns she has about the rise of antisemitic incidences in Hungary. In her view, after the landslide victory of Hungary’s right-wing party in the country’s national elections on April 6, “things do not look very promising for Hungarian Jews.” She is irritated with plans (proposed by the previous government) to erect a monument suggesting that Hungary was occupied during the Second World War and that any fault lies with the German Nazis. A very feisty Judith Weiszmann is here to say otherwise – however, she is also here to remind us how much good one person can do in the world and that we all have options to work at peaceful coexistence.

Karen Ginsberg, an Ottawa-based writer, considers herself blessed to count Judith as a friend.