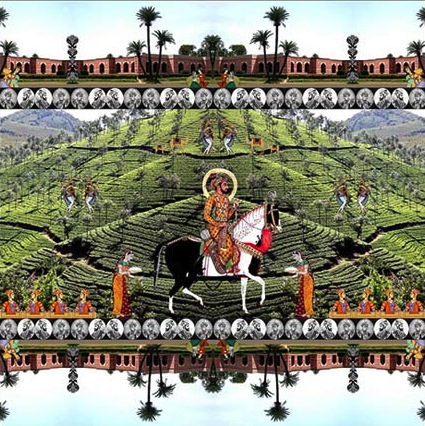

The gallery includes work by Almagul Menlibayeva of Kazakhstan. (photo from AMOCAH)

When people in Israel saw that Belu-Simion Fainaru and his partner Avital Bar-Shay were considering opening yet another art museum/gallery, some eyebrows were raised. But what this dynamic duo in life and in art had in mind was much more than another one-dimensional art space. Their far-reaching ideas will likely quiet the doubts of any naysayers.

Fainaru and Bar-Shay, both Jewish artists living in Haifa, decided to create an art meeting space for Jewish, Christian, Muslim, Bedouin and Druze artists – a place where they could display their art alongside one another. They created the Arab Museum of Contemporary Art and Heritage (AMOCAH) in Sakhnin in the Lower Galilee, which was declared a city in 1995 and has a population of 25,000 of mostly Muslims and a minority of Christians. It also is home to a significant population of Sufis, Muslims who adhere to a mystical stream of Islam.

Bar-Shay and Fainaru originally met in Israel. Fainaru made aliyah from Romania in 1973. A successful visual artist, he has curated exhibits around the world, making international connections along the way. Bar-Shay is an Israeli-born artist, designer and architect. She has exhibited in Israel and abroad and has vast experience in public art, working as a cultural entrepreneur. She specializes in artistic activity in the periphery.

The idea for AMOCAH started with Fainaru and Bar-Shay initiating and curating the Haifa Mediterranean Biennale four years ago. This led to a second biennale in 2013, which took place in Sakhnin. At the Haifa biennale, they used shipping containers to exhibit the artwork. In Sakhnin, the biennale was held in a building that the town’s mayor offered for the occasion.

“Right now in Israel, a lot of … Jewish people feel a special energy when it comes to Sakhnin,” said Fainaru. “So, we did this big project in the Sakhnin area, where a lot of Jewish people are already using various art mediums to bring communities together.”

Fainaru said that the various communities do not usually do things together and, even within the Arab community, Muslims and Christians generally keep to themselves.

“The art will have an urban dimension and we can approach art for a population that’s not very familiar with contemporary art,” said Fainaru. “We think it’s important to decentralize the art scene in Israel.”

Going with the biennale (Italian for every two years) concept seemed the most feasible, with politics and budgets in Israel regularly being in flux. “We had a big project with the Ministry of Education, but a few months after we decided to move ahead with [the minister], he [had] just resigned,” noted Fainaru, as an example.

While the idea of a biennale was born 100 years ago in Venice, Fainaru and Bar-Shay wanted to go with that premise and added a new twist – creating a biennale melting pot of cultures, and eventually transform that into a permanent museum in Sakhnin.

“We think countries around Israel and the Mediterranean should cooperate and exchange ideas in the area of contemporary art,” said Fainaru. “We put a lot of emphasis on education and doing workshops with artists from abroad.

“We want to develop projects under the umbrella of the biennale and museum, also with Jewish and Arab children – the next generation – to communicate and get to know each other, have fewer misconceptions, and make a better living here not based on violence.”

It took some time and meetings with the right people to get the Sakhnin museum off the ground. Fainaru and Bar-Shay met with the mayor of Sakhnin, Mazin G’Nayem, who was open to the idea. The mayor spoke with his culture deputy and the pieces began to fall into place.

“He [the mayor] thinks it’s important to have contact between Jews and Arabs, as we have to live together,” said Fainaru. “He understands that art will help the people of Sakhnin and promote coexistence between Jews and Arabs. He saw that with the football team he put together that has Jews and Arabs playing together.”

During the first biennale in Sakhnin in 2013, Sakhnin was flooded with people coming to participate in the festivities. AMOCAH is open to the public and, so far, the majority of the visitors have been students of contemporary art. The educational component of the museum is still being developed. “We hope, with these educational activities with the biennale, Israel’s sense of art will become known to people all around,” Fainaru said.

AMOCAH carries art from the various cultures in the region and from different religions, but Fainaru is especially proud of the art coming from countries without political ties to Israel, like Syria, Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan and Turkey.

“Normally, relations between Israel and Turkey are very bad,” he said. “Even I was dismissed from a biennale exhibition in Turkey, because of war between Israel and Gaza [last] summer.”

To facilitate cooperation between the Jews and Arab artists involved, the biennale and the museum are being organized by both communities.

“Tel Aviv-area people are self-sufficient in art, culture, cinema, food … in life,” said Fainaru. “They don’t feel they have to go to another place inside Israel. But, in the periphery, what we’re doing is creating an alternative activity in art in Israel and having an influence on life here – making a change and bringing art to people while incorporating cooperation between Jews and Arabs and neighbors around. This is just a beginning.”

The next Sakhnin biennale is scheduled for the end of 2015, with Fainaru and Bar-Shay already working to bring in the works of many new artists from Israel and abroad.

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.