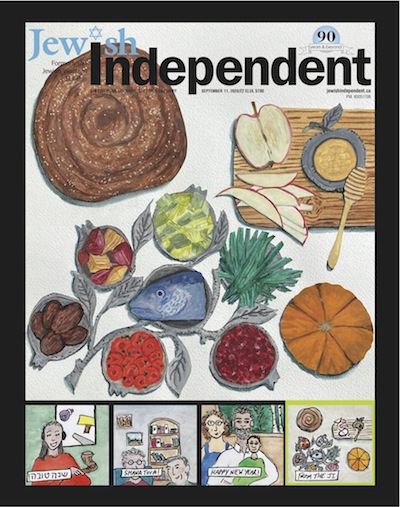

(photo by Shelley Civkin)

Not only did I never imagine that I wouldn’t be able to hug and kiss my family during Rosh Hashanah dinner; I didn’t even get to see them this year. Everyone is still hunkering down, keeping out of COVID’s way and staying close to home. At least most people are.

In case you’re one of those people waiting for things to “get back to normal,” I hate to be the one to deliver the bad news, but there is no going back. Normal is a setting on a dryer. Once the world claws its way out of this pandemic, we will be forever changed. Like grief and loss over time, we may not feel worse, but I guarantee we’ll feel different.

What will come out of this topsy-turvy pandemic is something much better. I’m hopeful that everything we’ve lost and sacrificed will be not only rectified, but made even more hopeful, soul-sustaining and life-affirming. I struggle to say these words, because it sounds downright arrogant, considering the losses people have suffered in the last many months, physically, financially and emotionally. But, if I choose to take the other fork in the road, it’s a dark and scary path, and I just don’t want to go there.

This Rosh Hashanah, like every Rosh Hashanah, we celebrated. Just differently. There was no fanfare. There was no cooking. There were no guests. Not even family. Being cautious by nature has stood me in good stead so far this year, and there was no way I was risking it all after such a long haul. So, we scaled down the physical celebration and revved up the spiritual one. We read more about the High Holiday rituals and their significance this year than ever before; we recited the blessings more powerfully than in the past; and, from our very core, my husband and I sincerely wished each other a healthy, sweet and good new year. And we meant it like never before.

In past years, I would fuss and bother and cook and bake. This year, I didn’t have the emotional or physical koach (strength) for it all. Preoccupied with health challenges, I decided to take the easy way out and have our meals catered from Chef Menajem. Not only was the food spectacular, but it made things (read: pandemic isolation) a bit easier to accept. I set an elegant (if empty) table, got out my silver candlesticks, draped the sweet challah with my homemade Yom Tov challah cover, and we proceeded to eat Rosh Hashanah dinner alone. Just the two of us. It was slightly eerie, but, at the same time, absolutely perfect. And, yes, that’s an acorn squash adorning the table. I didn’t even have the wherewithal to track down a pomegranate. And, while an acorn squash isn’t a first fruit, it was my first squash of the year. I’m sure G-d will understand.

A feeling of tremendous blessing came over me as I realized just how lucky we are to have each other, my husband Harvey and I. Thinking of our single, divorced and widowed friends, and the loneliness and isolation they’re feeling right now, my heart breaks. How I would have loved to invite those friends to our home to join our modest New Year’s celebration. A little wine, a lot of food, some brachot, some honey cake. But COVID-19 was having none of it.

Turns out, COVID-19 is a big, huge bully. It doesn’t care one iota about anyone’s feelings; it doesn’t want to know from suffering or depression or desperation. But, we know, and we’re fighting back. With joy. As many of you know, lots of local Jews took to the parks and beaches to hear the shofar on Rosh Hashanah this year and I, for one, infused much more meaning into the holiday than I can ever remember. Because I could. And it was a very conscious choice. Not only is Rosh Hashanah part of our heritage, it’s our right. And we sure as heck weren’t going to let COVID take that away from us, too. Everything just seemed to magnify this year – the holiness, the urgency, the depth of feeling. And, while it may have seemed a bit lonely from the long view, it was nothing short of superb close up.

Stepping in to fill the spiritual void so many of us are experiencing this year, there are dozens (if not hundreds) of rabbis and synagogues around the world offering online Jewish learning. I want to say a personal thank you to all of you. You are a lifeline, literally. Because of you, I am studying and learning more about my Judaism, and participating in its mitzvot to an extent that’s surprising even me. Never before has finding meaning and purpose taken on such enormous importance. Our mission isn’t just to stay alive; it’s to thrive, even in the face of this brutal pandemic. We, as a people, are stronger than that. Unfathomably stronger.

The pandemic has, for the most part, brought out the best in humanity, and certainly within our Jewish community. People are helping strangers, feeding strangers, doing errands for strangers and wanting to do more. And it’s not just Jews helping Jews. It’s Jews helping everybody. Truly, the world has become one people. When we climb out of our little hidey holes and show up for life in the most positive, compassionate ways we can, each of us makes the world a bit better. And the light grows.

Not a single one of us will come out of this pandemic the same person. We do have the choice to become a better version of ourselves though. Stretched beyond our comfort zone, tired from doing too little for too long, we do have the ability (and the desire) to puff ourselves up and accept the challenges facing us. Or even go beyond. If that’s all that’s within our control right now, that’s enough.

No one is asking us to perform miracles – that’s not in our job description anyway. All we’re being asked to do is help one another through this challenging time. Even just a kind word can get the job done. Do something. Do anything.

Shelley Civkin, aka the Accidental Balabusta, is a happily retired librarian and communications officer. For 17 years, she wrote a weekly book review column for the Richmond Review. She’s currently a freelance writer and volunteer.