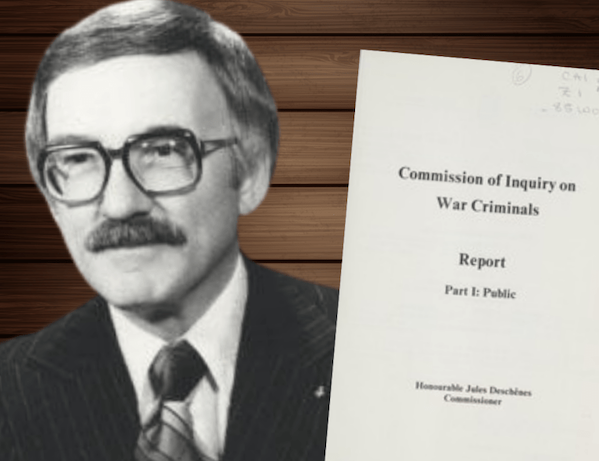

Justice Jules Deschênes, who was appointed by the Canadian government in February 1985 to oversee the Commission of Inquiry on War Criminals in Canada. (screenshot from B’nai Brith Canada)

For nearly four decades, Jewish human rights organizations have been trying to figure out how Nazi war criminals were able to gain citizenship and refuge in Canada following the Second World War. Why were high-ranking members of the Nazi Allgemeine Schutzstaffel (Nazi SS) and Waffen SS troops who fought on Germany’s behalf considered eligible for Canadian citizenship? And who were they? What were their names?

The answers to many of these questions can be found in an obscure list of reports held in government archives. Since 1985, when the Deschênes Commission was appointed to investigate allegations that Nazi war criminals were living in Canada, B’nai Brith Canada and other Jewish organizations have been urging the federal government to release all the commission’s findings. Those records include an historical account of Canada’s post-Second World War immigration policies, written by historian Alti Rodal (the Rodal Report).

“We have always felt that providing the general public with a greater understanding of Canada’s ‘Nazi past’ is a significant venture to providing closure to that time period,” explained Richard Robertson, B’nai Brith’s director of research and advocacy. “This is important because, at a time of rising antisemitism, where there are less and less survivors of the Holocaust around, it is essential that we furnish educators and advocates with as many tools as possible to enable as fulsome a teaching of the [history of the] Holocaust,” including, noted Robertson, those decisions that may have indirectly made it easier for Nazi perpetrators to escape prosecution.

The Hunka affair

Last September, a critical portion of the documentation was made public by the federal government after it was revealed that a former member of the Waffen SS Galicia Division, Yaroslav Hunka, had received a standing ovation in Parliament. Human rights advocates wasted no time in calling for the rest of the Deschênes Commission’s documents to be released, arguing that the unredacted reports could help further Holocaust education in Canada and avoid such mistakes. More than 15 groups, representing Jewish, Muslim, Iranian and Korean ethnic communities and interests, supported B’nai Brith’s petition and, on Feb. 1, the Trudeau government released the bulk of Rodal’s account.

That move has given human rights organizations access to a wealth of information about the politics, the thinking and the apprehensions that often steered the government’s decision not to prosecute or extradite war criminals. Compiled as an historical account of Canada’s post-Second World War policies, the 618-page redacted Rodal Report provides details that aren’t revealed in Deschênes’ deliberations.

Set against the backdrop of today’s rising antisemitism, the report illustrates that Canada’s current struggle to balance the needs of those targeted by antisemitism and discrimination with other democratic principles, like free speech and privacy, is nothing new.

According to Rodal, Canada’s postwar immigration policies were heavily influenced by a belief that extraditing naturalized Canadian citizens for war crimes would be, in the words of Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau, “ill-advised.”

“Trudeau’s concern,” Rodal wrote, “was that the revocation [of citizenship of an alleged war criminal] could alarm large numbers of naturalized citizens who would be made to feel that their status in Canada could be insecure as a consequence of the politics and history of the country they left behind.”

And Pierre Trudeau was not alone in his reticence to bring Nazi war criminals to court.

“All those goals which Canadian society has set for itself can certainly not be achieved by short-circuiting the legal process in the hunt for Nazi war criminals,” the commission wrote, while examining whether a military court might be an appropriate venue for litigating charges of war crimes.

By the time the commission concluded its research, it had effectively struck down every available legal mechanism for pursuing action against most former Nazis living in Canada. The Deschênes Commission determined that war criminals could not be prosecuted under Canada’s Criminal Code, but neither could they be tried by military tribunal. Nor could they be successfully prosecuted under the Geneva Conventions for acts of genocide or crimes against humanity. And Canada’s extradition laws would be ineffectual in many instances, including when it came to approving requests from Israel. Israel didn’t exist at the time of the Holocaust, the commission reasoned, and thus didn’t meet Canada’s requirements for requesting extradition of Second World War criminals.

New laws, similar challenges

Canada’s only remedy would be to amend its laws going forward. In 2000, nearly 14 years after the release of the Deschênes Commission’s report, the Crimes Against Humanity and War Crimes Act was given Royal Assent. Antisemitism, hate speech and hate crimes are now federal offences as well, covered under Section 319 of the Criminal Code. However, some legal experts say the process of bringing charges of antisemitism or hate crimes to court remains too onerous.

In June, the Matas Law Society and B’nai Brith hosted an educational webinar on the legal strategies available to Canadian lawyers when pursuing charges of antisemitism. Gary Grill and Leora Shemesh, two Toronto-based lawyers who have recently represented victims of alleged antisemitism in Ontario, offered different views as to why it is so hard to bring a hate crime to court.

“We have the tools,” acknowledged Shemesh, “we’re just not effectively using them.” She said she has represented several alleged victims of antisemitism and, in each one of the cases, the charges were later dropped.

Grill, on the other hand, suggested that the issue had to do with initiative. “It’s about political will” when it comes, for example, to ensuring that prosecutors understand that “death to Zionists” is veiled hate speech and should be prosecuted as antisemitism. “The education is easy,” he said. “We can educate prosecutors. We can educate police. It’s not a problem. [But] this is about will. It’s not about law.”

“There are problems with certain [parts] of Section 319 and [its] enumerated defences,” Shemesh said. “Prosecutions under the Criminal Code for the promotion of hatred … require the approval of the attorney general to proceed, which, I say, has partially explained why such prosecutions have been rare in Canadian jurisprudence.”

In Robertson’s opinion, there can be value in legislative oversight. The attorney general’s sign-off “is a safeguard to ensure that our hate crimes legislation … is only utilized when warranted. I believe it is designed to prevent overuse,” he said. “Listen, there’s nothing wrong with that. There’s nothing wrong with having checks and balances to ensure that the proper charges are being laid and the severity of these charges warrant such. The issue is the reluctance of the attorney general to sign off on these charges and the procedural, I would say, slow-downs in effecting the sign-off. These are the issues. If we can perfect the procedures around the sign-off, then this is a completely fine check and balance.”

As for addressing the rise in antisemitism that Canada is experiencing today, Robertson believes the answer lies in ensuring Holocaust education is available and continues. That requires ensuring public access to the documents that most accurately tell the story – including those of Canada and other allied nations.

“With the recent issues that we’ve seen regarding immigration into Canada, I think [the Deschênes and Rodal reports serve as a] narrative that is more relevant than ever. I think it is important for us to understand our mistakes of the past so that we don’t repeat them in the future,” Robertson said. “And, as well, when it comes specifically to Holocaust education, I think it is important for Canadians to appreciate the level of complicity, if there was any complicity, in our government helping Nazis escape prosecution following the culmination of the Holocaust in World War II…. It helps to paint the totality of the picture of just how widespread the Holocaust was.”

Robertson said Canadians often think of the Holocaust as a “European issue,” that it only adversely impacted Jews in Europe. “So, understanding Canada’s role and [the Holocaust’s] aftermath helps to globalize the narrative, and perhaps that will help Canadians to better appreciate the truly global impact of the Holocaust [and the trauma] that is still ongoing.”

To date, most of the Deschênes documents have been made public, with the exception of Part II of the original report, containing the identity of members of the Nazi party who were granted immigration to Canada. The ancillary documents, such as the Rodal Report, also contain information that has not been made public. B’nai Brith Canada continues to lobby for their release.

Jan Lee is an award-winning editorial writer whose articles and op-eds have been published in B’nai B’rith Magazine, Voices of Conservative and Masorti Judaism and Baltimore Jewish Times, as well as a number of business, environmental and travel publications. Her blog can be found at multiculturaljew.polestarpassages.com.