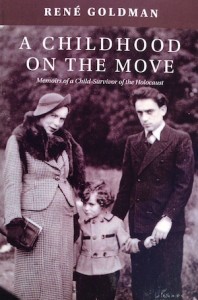

Breakfast at Andrésy circa 1945. René Goldman is holding his bowl out for more food. The children peering through the windows are from another dining room, who had likely finished their meal but had not yet been given permission to leave. (photo from memoirs.azrielifoundation.org)

René Goldman’s account of his childhood – A Childhood Adrift (Azrieli Foundation) – is set in Belgium and France during the Second World War, when Hitler’s plan was to annihilate all European Jews. Each European Jewish child was automatically sentenced to death. Only between six and 11% of European children survived the Holocaust. Ironically, this memoir describes both a heartbreaking and an uplifting story of one Jewish boy’s struggle to stay alive and sane despite all odds against him.

A Childhood Adrift is both personal and, at the same time, an important historical document. The story, written with a spatter of tongue-in-cheek humour, is a fascinating labyrinth of multiple narratives; stories within stories. It is not only about René the child, but also René the man, who revisits the past and examines the wounds left by war.

Goldman weaves his experiences throughout the periods of war and postwar, when he is a young man who travels back to the places that sheltered him and other children lost in the horror of war. The entire narrative is skilfully infused not only with historical and political facts but with the geography of various places so poignantly described one can feel and see them.

Goldman writes about the time when children lost parents, siblings and homes. These children had to depend on the kindness of strangers or were left alone to fend for themselves.

Goldman was 6 years old when the Nazis invaded his native Luxembourg, where he was born, and Belgium, where his family had taken refuge. In 1942, the family fled Belgium for France. From the last station before the French border, they walked on foot to the Demarcation Line between the German Occupied Zone and the Free Zone. No sooner did they cross the line than they were arrested by the French police, who were rounding up Jews escaping from the Occupied Zone, and the family was interned in Lons-le-Saunier. On Aug. 26, Goldman and his mother were taken to the city’s train station for deportation. His aunt appeared from nowhere and tried to take him away, but to no avail. Eventually, she found someone in authority to send two officers to rescue the young boy and save him from boarding the train. His mother was already in one of the cars waving goodbye as the train was pulling out of the station. This was the last time Goldman saw his mother. He was 8 years old.

His father disappeared that morning and it was only in 1944 that Goldman was reunited with him for a brief time, until his father was arrested and taken away. Only after the war did Goldman find out that his father died at the end of the death march from Auschwitz, in January 1945.

In 1942, Goldman was placed in the care of the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants) and brought to Château du Masgelier. After two weeks, he was taken to the village of Vendoeuvres, where a young couple offered to take care of him. Soon afterward, the Free Zone was invaded by the Germans.

What followed for Goldman were moves to several homes due to the changing circumstances, which necessitated a constant search for safe places for children.

Left an orphan in 1945, Goldman was placed in the care of the CCE (Commission Centrale de l’Enfance), an organization inspired by communist ideology, which was instrumental in shaping his political beliefs. His faith in this system remained unshaken until he lived in Poland for three years, when he became disillusioned, even shocked, by it.

He writes, “I can now in all candidness recognize that I caught myself wondering whether communism was not the greatest lie of the century, if not of all time.”

Goldman’s narrative strength, among his many others, leans towards the lyrical.

One of the immediate postwar places to which Goldman was moved in France was the town of Andrésy and its Manoir de Denouval, which inspired poetic instincts in him. Here, he found the beauty of gardens and serenity, a “sanctuary” that shielded him for a time from his loneliness and the postwar chaotic reality. Interestingly, Marc Chagall, who donated funds for the children’s care, would occasionally visit the manor.

“I was enthralled with the Enchanted Manor,” writes Goldman. “It nourished in me a fascination with mystery as I explored it for hidden nooks and ventured up the narrow winding steps that led to the turret, sometimes even in the dark of night.” And, indeed, these were dark times in the young boy’s life for it was then that he realized he was an orphan.

Friendships played a huge part during the war and in the postwar period. In the boys and girls Goldman befriended along the way, and some of the kind teachers, he found a certain relief from the loneliness he felt, and from the lack of affection and support. One person who played an important role in his life was Sophie Micnic, who became his caregiver and friend. This woman, a founding leader of the MOI, the Jewish communist resistance movement in Paris and Lyon during the war, later became the director of CCE. It was she who took Goldman under her wing, and recommended that he live in the “Enchanted Manor.”

A Childhood Adrift – a must-read – is a powerful testimony of a child’s response to the calamities of war and their everlasting imprint on his life. It is also a statement of courage and survival in the face of adversity. Eventually, Goldman developed a tremendous hunger for knowledge, education and a desire for communication in as many as 10 languages.

In the last section of the book, the author reveals himself as a poet and a grown man still deeply immersed in his past.

Lillian Boraks-Nemetz is a Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre outreach speaker, an award-winning author, an instructor at the University of British Columbia’s Writing Centre and the editor of the No Longer Alone section of VHEC’s Zachor, in which a longer version of this book review was originally published. René Goldman will be the keynote speaker at the community’s Kristallnacht commemoration on Nov. 5, 7 p.m., at Congregation Beth Israel. Copies of his memoir will be distributed to those in attendance. Holocaust survivors are invited to light a memorial candle. The ceremony is presented by VHEC, Beth Israel and the Azrieli Foundation. For Pat Johnson’s review of Goldman’s book, which was initially called A Childhood on the Move, visit jewishindependent.ca/fragmented-childhood.