An inscription on a water fountain built by Suleiman the Magnificent. (photo by Ariel Fields)

When it comes to Jerusalem, the writing really is on the wall. The problem is, some people (easily recognized, as they go around saying “it’s like talking to a brick wall”) will try to convince you walls can’t tell you anything. Don’t listen. If you ignore Jerusalem’s walls, you’ll miss out. The following matryoshka/babushka story (or story within stories) shows that “walls are the skin of the residents,” as the muralist cooperative CitéCréation is fond of saying.

Admittedly, you might initially doubt whether writing on the wall matters. To quell your uncertainty, here is what Tel Aviv University’s Prof. Jonathan Price has to say: “Inscriptions are an important and unique historical source. They provide information in many areas no other source can provide.”

Thus, while there’s no CD of the trumpet/shofar playing, we know that trumpet blasts from the southwest end of the Temple Mount indicated the beginning and end of the Sabbath. How? In his extensive history, The Wars of the Jews, Flavius Josephus writes about this practice.

The truly astounding physical evidence, however, is a stone carved sign now located in the Roman/ Byzantine section of Jerusalem’s Israel Museum. The inscription on this first century CE stone reads, “‘To the place of the trumpeting.” The stone directed the Temple kohain “trumpeter to the high point on the Temple Mount, where he would announce the beginning and end of the Sabbath.”

An archeologist described its discovery. It was found in the “debris from the dismantled walls, engraved on an eight-foot-long piece of limestone. The stone has a rounded top indicating it was a kind of parapet situated on top of the wall or the tower at the southwest corner of Herod’s giant Temple Mount. Unfortunately, the clearly readable inscription is broken off, so we only have the beginning of it.”

The trumpeter’s corner had a distinct vantage point. From his post, the trumpeter looked out over ancient Jerusalem, from the City of David to the Upper City in the West. When he gave a blast, even the merchants and shoppers in the markets heard.

Moving slightly away from the Old City, we come to an ornate Ottoman inscription just above the southern end of Sultan’s Pool. It reads: “[There] has ordered the construction of this blessed sabil, our master the Sultan the greatest prince and the honorable Khaqan, who rules the necks of the nations, the sultan of the [land of] Rum, the Arabs and the non-Arab [’ajam], the Sultan Suleiman, son of Sultan Selim Khan, may God perpetuate his reign and his sultanate. On the date of the tenth of the month of Muharram the sacred, in the year of 943 [29 June 1536].” (Ottoman Jerusalem, Auld and Hillenbrand, eds., 2000)

This sabil (drinking fountain) served the many passing pilgrims. The Ottoman ruler Suleiman the Magnificent built five more sabils inside the walls of the older city. Moreover, several other sabils (the earliest dating back to the Byzantine period of the sixth/seventh century) have been excavated at this same location.

The drinking fountain’s water came from an aqueduct originating at Solomon’s Pools, near Bethlehem. Importantly, this aqueduct primarily serviced the Temple Mount area. To insure an adequate water supply, Sultan’s Pool (today an outdoor concert venue) was a floodwater reservoir. Just a few years ago, archeologists uncovered a Second Temple period bridge that stood over the adjacent ravine of Ben Hinom Valley. The original bridge maintained the elevation of the path along which the water coursed. In 1320 CE, the Mamluks rebuilt the bridge. Two of the original nine arches supporting the bridge were excavated to their full three-metre height.

A relatively short walk from the fountain, but with a significant leap in time, we arrive at the Hebrew year 5694 (corresponding to 1933-1934). At that time, builders completed work on a structure at 6 King David St. As the country was still controlled by the British (the Mandatory period lasted from Sept. 29, 1923-May 14, 1948), the Hebrew stone dedication might be termed both prophetic and Zionist. The inscription from Psalms 102:15 reads: “Your servants take delight in its stones and cherish its dust.” Heads up, however, to view this stone, as it is high on the right side of the entranceway.

No matter what you think of the Mandatory period, most people will agree that the British constructed attractive and made-to-last Jerusalem streets and boulevards. Although King George Street has changed tremendously since Israel gained independence, the stateliness of the road’s 1924 commemoration is visible in the dedication stone on the side of what is now a woman’s clothing store. The esthetically pleasing inscription is carved in the languages of the time: English, the official language of the British Crown has a central spot on the stone. It is flanked by slightly smaller Hebrew and Arabic translations.

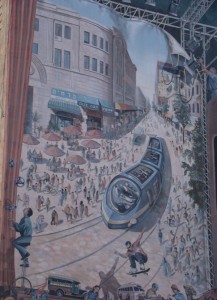

They say a picture is worth a 1,000 words, so here goes: Across from the above inscription, where King George, Strauss and Jaffa Road intersect, look up to see what was for 10 years regarded as a “time-warp” fresco. In 2001, the French art group CitéCréation painted a long exterior building wall depicting the Jerusalem Light Rail system. Since the light rail only began running at the end of 2011, for years Jerusalemites considered this painting a bad joke. Like many other Jerusalem projects, this one finally came into being years after its original promised inauguration.

Despite a violent summer and fall, the Jerusalem Light Rail demonstrates that the city’s ethnic and religious groups can – and do, literally – come into close contact. Jerusalem’s train is an example, albeit a fragile coexistence.

In sharp contrast to the slow development of the light rail, the wall project on the Gerard Behar Theatre (its address is 11 Bezalel St.) shows how quickly things can get done, if one really works at it. In 1976, Gavriel Cohen painted a huge building mural in just 92 days. Humorously, this 18-metre-wide painting is entitled “Around the World in 92 Days.” When you see the painting, you will understand its “play” on the title of Jules Verne’s famous adventure story.

Like Verne, Cohen was born in France. Moreover, the Jerusalem Foundation donor who underwrote the building’s renovation was himself a millionaire French Jew. He named the building after his son, Gerard Behar. Today, the wall has added significance, as many French Jews are making Israel their home. The Jewish Agency reported nearly 7,000 French Jews made aliya in 2014, doubling the number of the preceding year.

We now move back in time to the Hebrew year 5632 (1872). In the tiny Jerusalem neighborhood of the House of David – the fourth neighborhood built outside the walls of the Old City – there is another inscription above the doorway of what (with controversy between different religious blocs) has recently become a yeshiva. David Reiz, a Jew from Jonava, Poland (today the Republic of Lithuania) donated the money to build this area. The Hebrew stone dedication contains a description of the 1872 purchase of the lot and the subsequent building of the apartments and a study house (bet midrash). The home of Rav Kook (first chief Ashkenazi rabbi of Mandate Palestine) and the popular dairy restaurant Ticho House (currently undergoing repair) are a few steps away. The square courtyard in which the inscription is found still has the wells residents used for their household needs. Reportedly, today’s residents are a mix of doctors, artists and yeshiva students.

Even if they never took up residence in Israel, over the years people of different denominations have considered Jerusalem to be their centre of the world. Thus, in front of Jerusalem’s City Hall, there is a large reproduction of Heinrich Bünting’s 1581 map of the world. Bünting (1545-1606), a German Protestant pastor and theologian with a strong interest in cartography, created a map (included in his printed map book) featuring a three-leaf clover (which to this day is still part of his native Hanover’s coat of arms). Europe is the western leaf, Asia is the eastern leaf and Africa is the southern leaf. Jerusalem lies at the centre of the clover.

As Hebrew University’s Prof. Rehav Rubin (1987) wrote: “These maps do not teach us anything about the appearance of the city in ancient times, but from them we learn how Christian Europeans and the map-makers themselves saw sacred texts and the place of Jerusalem in the sacred texts.”

So much of Jerusalem’s history is laid out on its walls; come visit to discover it.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.