King Manuel I of Portugal (1495-1521) had a problem. To marry Princess Isabella of Spain, he consented to the request of her parents – Ferdinand and Isabella – to rid Portugal of its Jews. But Manuel wanted to keep the Jewish citizens close by, for their economic benefits (money and skills). His solution? In 1496-7, he forced Jews to convert. (He also expelled the country’s Muslims.)

Manuel believed that New Christians – this population is likewise referred to as conversos, anusim or Crypto-Jews; marranos is a derogatory term that should not be used – would continue to boost the country’s economy. It should be noted that Jews in Portugal already paid a special poll tax and a special property tax.

Even after they were forcibly converted, Portuguese Jews could not live wherever they wanted. They lived in separate quarters referred to as judiarias, what we might call ghettos. They worked as artisans and rural labourers, weavers, tailors, cobblers, carpenters, leather tanners, jewelers, and every branch of the metal industry, ranging from ordinary blacksmiths to armourers and goldsmiths.

Several Jews nonetheless reached prominence in medieval Portugal. Among them was Abraham Zacuto, originally from Spain. Portuguese King John II invited Zacuto to be the royal astronomer. The king wanted Zacuto to chart a sea route to India. Unlike most of his fellow religionists, Zacuto managed to flee Portugal after King Manuel imposed conversion on the country’s Jews.

There was also Isaac Abarbanel, who was King Afonso V’s treasurer. Yehuda Even Maneer was the richest Jew in the kingdom and, for that reason, was appointed Portugal’s finance minister. Master Nacim, a Jewish eye doctor, was accorded certain privileges because of his professional skills.

Before King Manuel decreed the forced conversion, the Jewish community of Tomar built a synagogue, in spite of attacks orchestrated against them and other Jews in the country. Unfortunately, the building was used for its original purpose for only a short period, after which – for years and years after the forced conversion – it was used by the Church. The town itself became one of the sites of the Inquisition tribunal. Today, the synagogue has been renovated and is considered a national monument.

Crypto-Jews continued to covertly practise Judaism. In the town of Porto, for example, the Crypto-Jews secretly operated a synagogue, hiding it from the Inquisition.

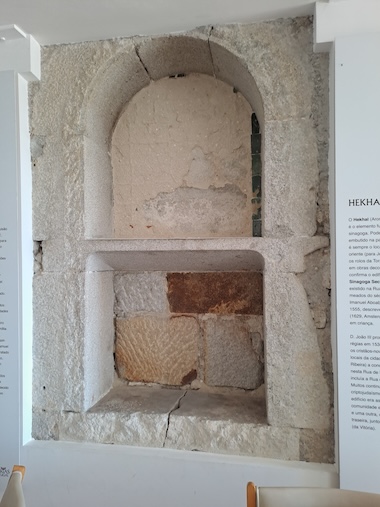

In 2013, a renovation project at a facility for Portuguese senior citizens turned up an amazing find. Hidden behind the eastern wall of the dining room was a Torah ark, or aron kodesh, carved directly into the stonework separating the building from its neighbour. There were two compartments, a square space topped by a slightly larger arched tablet-shaped opening, with space for approximately six small Torah scrolls. Besides this relatively recent discovery, we have the 16th-century testimony of Immanuel Aboab, a native of Porto. (The late Yom Tov Assis, who was a professor at Hebrew University, had likewise been trying to locate where such an aron kodesh was located in the area.)

It was common among Crypto-Jews to light one Shabbat candle in a secret cabinet. There was also an emergency tool for snuffing out Shabbat lights if it was suspected that a Christian neighbour was spying. To make Shabbat different from other days, these secret Jews ate no meat. Purim was marked by three days of fasting beforehand. Passover was celebrated two days late, so as to throw Christians off the track. Other secret Jews took the risk of undergoing circumcision.

Within limits, these Crypto-Jews read psalms and recited the Shema, didn’t work on Shabbat, didn’t eat pork and fasted on Yom Kippur. Manuel (Abraham) de Morales passed out manuscripts of what he thought were important points to know about Judaism. But most of the Jewish customs were orally transmitted from mother to children.

Not surprisingly, the period before the forced conversion was not totally free of tension between Jews and Christians: Franciscan and Dominican clergy walked through judiarias, ready to convert Jews. Moreover, Portugal’s new merchant class was apprehensive about the influence of the Jewish citizens and their capital. Under the reign of João I (1385-1443), new laws obliged Jews to wear an identifying sign on their clothes and imposed curfews on the judiarias. There were scattered outbreaks of violence, like the attack on the Lisbon judiaria in 1445, in which many died.

After the forced conversion, New Christians would be charged with being infidels, not heretics. These New Christians generally adopted Christian given names and Old Christian surnames. They probably did this to deflect attention. But harder times still followed for Portuguese Jews, with the massacre of 2,000 conversos in Lisbon in 1506 and the Portuguese Inquisition, which began in 1536. Inquisitors would come to a town and tell the gentile population that they were looking for secret Jews. They would present a list of suspicious behaviour to look for.

In medieval Portugal, turning in New Christians became a profitable venture. Arrested conversos had their assets seized by members of the Inquisition. Occasionally, Church officials would accept bribes for temporary pardons.

Apparently, if a New Christian approached an inquisitor, he had a chance of redeeming himself by admitting that his family lit Shabbat candles or washed sheets for Shabbat. On the other hand, if an Old Christian accused a New Christian of still practising Jewish rituals and the latter denied the observances, he would face a worse outcome from his trial.

The number of Inquisition victims between 1540 and 1765 is estimated at 40,000. Punishment included being raised by a pulley with one’s hands behind one’s back. Convicted infidels were then burned at the stake.

The cruel punishments passed down by the Portuguese Inquisition drew large crowds of spectators. The crowds were akin to those who would come to watch bullfights.

Trials ceased after about 250 years, although Portugal’s Inquisition was not officially abolished until 1821.

Jewish informers should also be mentioned. These people, as can be imagined, found an open ear among Portugal’s prejudiced secular and religious leaders. If these traitors were discovered by the Jewish community, they might have had their eyes gouged out, their tongue removed or been put to death for putting the community at tremendous risk. So serious a crime was acting against one’s own people that even Maimonides condoned Jewish informers.

The impact of the forced conversion and the Inquisition continue to be felt. Take, for example, Belmonte, located in the northern part of Portugal. It has a small Jewish community that has retained the rituals of Judaism despite all the hardships and persecution. In the 1990s, when the idea of building a synagogue was raised, some Jewish community members were against it. Why? Because being a member of the anusim community was their cherished identity. Almost 200 years after the Portuguese Inquisition had been abolished, they couldn’t imagine living openly as Jews.

Estimates are that at least 20% of Portugal’s current population has anusim roots.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.