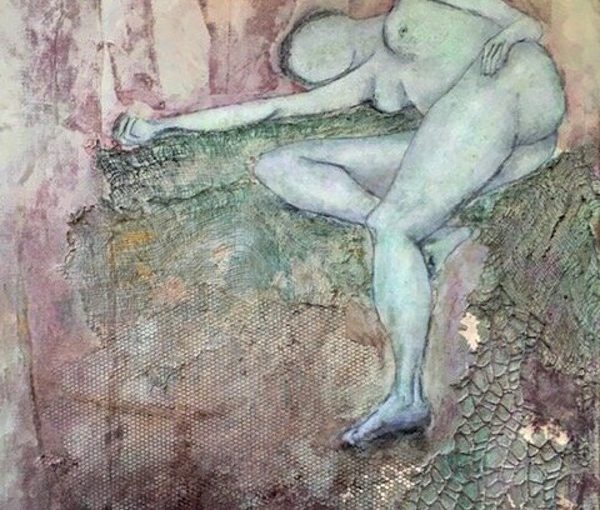

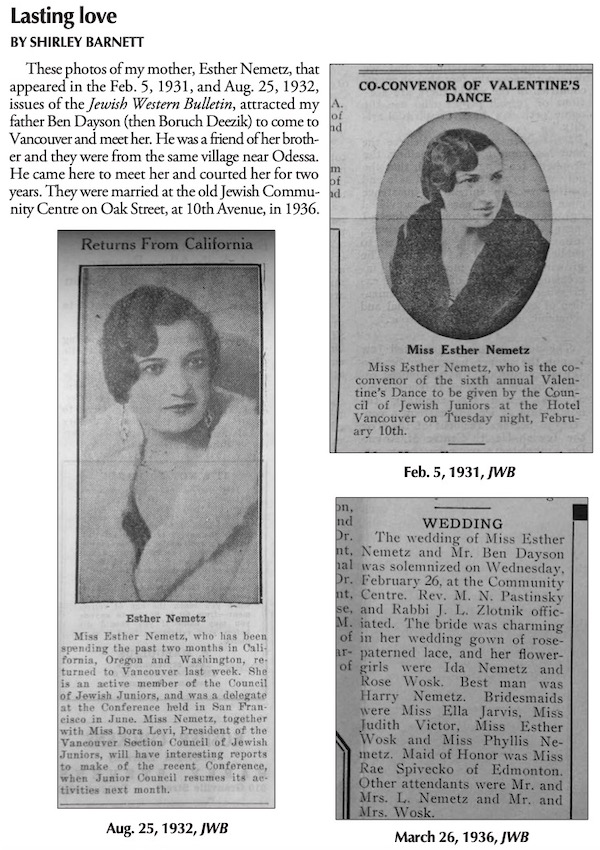

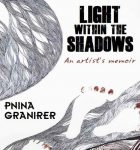

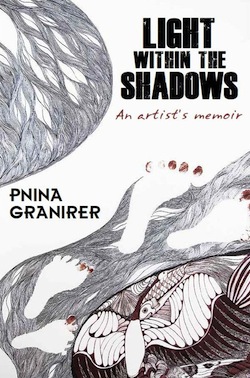

I am the proud owner of a Pnina Granirer work. More importantly, I am privileged to know the wonderful human being who is Pnina Granirer. After reading Light Within the Shadows: A Painter’s Memoir, I now know more about her art, its influences and styles, and her life, its joys and challenges. I also discovered that she writes as beautifully as she paints, and has a warm sense of humour.

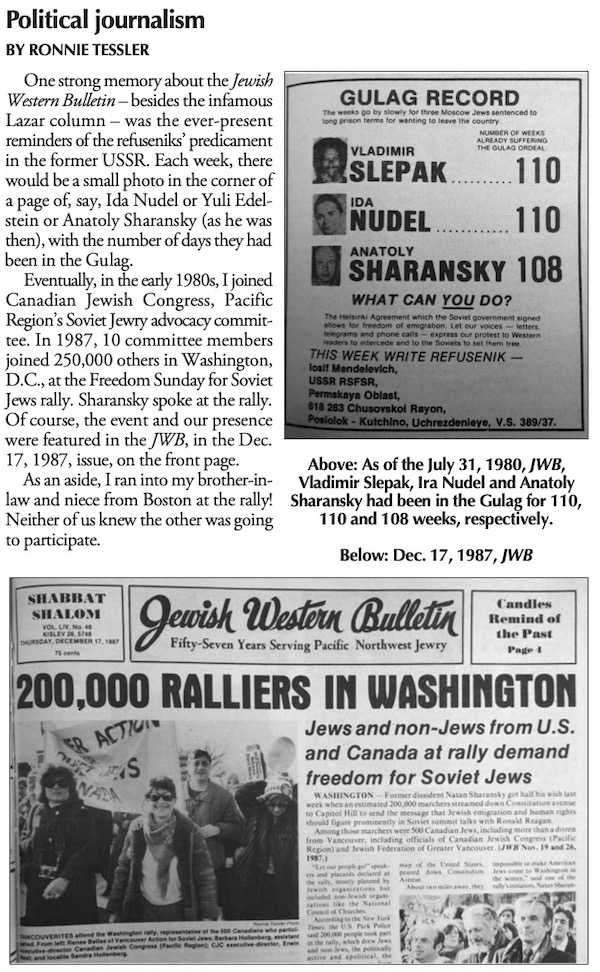

Each chapter features a relevant quote from people throughout history, something they said or, most often, wrote; people as diverse as Roald Dahl, Anne Frank and Shakespeare. In these and her own words, Granirer imparts not only her life story but her philosophies on creativity, education, identity, family, business.

“There are people who plan their lives meticulously, step by step – I have never been one of them,” she writes. “Of course, I had goals, but these were like signposts to be reached one by one, short-term endeavours without a specific plan for the faraway future. I rather liked the idea of floating along, steering my boat from time to time and hoping that I would reach my destination, whatever it was meant to be.”

And the 82-year-old has experienced many destinations on her continuing journey. In a May interview with the Vancouver Sun, she talked about having written a book twice the size of what was published.

“There were a lot more historical references, many stories about family members and some more memories – it was too long and had to be cut,” Granirer told the Independent.

About the possibility of another book, she said, “I’m thinking about this and how I could use some of the chapters that have been cut, but, at the moment, I’m far too busy with getting through with the exhibition. I need a quiet space in order to begin thinking about writing and hope that I’ll begin doing just that early in 2018.”

Granirer will do an artist’s talk at the Sidney and Gertrude Zack Gallery on Nov. 16 to open an exhibit of her work mounted in conjunction with the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival because the occasion also represents the launch of her memoir. The event is sponsored by National Council of Jewish Women. This is especially appropriate because one of the topics that Granirer explores in her memoir is the difficulty of being a mother, a wife and an artist. About the 1970s, when her two sons, David and Dan, were young, she remarks, “I had little contact with the visual arts community in general and its avant-garde segment in particular. I didn’t have much time for forging professional ties, as my world consisted of my husband and my sons, who were a great source of joy and a well of inspiration for my art.” In this period, she not only produced much work, but also took on teaching.

Granirer will do an artist’s talk at the Sidney and Gertrude Zack Gallery on Nov. 16 to open an exhibit of her work mounted in conjunction with the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival because the occasion also represents the launch of her memoir. The event is sponsored by National Council of Jewish Women. This is especially appropriate because one of the topics that Granirer explores in her memoir is the difficulty of being a mother, a wife and an artist. About the 1970s, when her two sons, David and Dan, were young, she remarks, “I had little contact with the visual arts community in general and its avant-garde segment in particular. I didn’t have much time for forging professional ties, as my world consisted of my husband and my sons, who were a great source of joy and a well of inspiration for my art.” In this period, she not only produced much work, but also took on teaching.

Her memoir – which includes pages of colour photographs of her work – is divided into three acts. It takes readers from Romania, her birthplace and where she grew up, surviving the Holocaust; to the safety of Israel in 1950, to where first her father, then the family, fled from the dangers of communist Romania; to the United States in 1962, where her husband Eddy, a math professor, could find work, as the recently initiated American-Russian space race saw Americans “pouring money and resources into research, hoping to be the first to put a man on the moon…. Mathematics, the cornerstone and essential building block of scientific research, was suddenly in high demand all over North America.” Three years later, the Granirers would make their way to Vancouver.

Granirer talks about luck throughout the memoir and, specifically, about a couple of “old hackneyed sayings” being true, that of being “in the right place at the right time” and of being “born under a lucky star.” “Events beyond our control do change the course of our lives,” she writes. And, while they don’t always do so for the better, Granirer chooses, at least in looking back, to appreciate her good fortune.

“Of course, I never even thought of being lucky at the time,” she admitted to the Independent. “One just lives one’s life as it comes along and only later, in retrospect, one sees the whole picture. Getting older allowed me to have a better perspective of the past and writing the memoir brought it all together. We kept saying for years how lucky our family was to live in Vancouver, but day by day there were ups and downs and the occasional complaints when unfortunate events happened – and they did. The memoir was a watershed for me and helped me see the serendipitous moments in my life when fate could have gone easily the other way.”

The light and shadows of the book’s title not only apply to the vividness of remembered moments and the darkness in which forgotten moments lie, but also the grey areas through which we must travel in life – the uncertainties, the aforementioned circumstances beyond our control.

When asked if she was a naturally optimistic person or developed into one, she said, “I probably am more of the former, although that does not mean that there are not times when I feel as if the world is collapsing on me. There have been hard times for me in the past, but somehow I seem to manage to get through. I just try to deal with the black thoughts, when they come. Nothing is really black-and-white, it’s through the shadows that we have to find our way.”

In addition to geopolitics, health and other uncontrollable issues, Granirer also had to negotiate the politics of the art world, in which she had to deal with many curators who “did not seem to be interested in art and artists, except as tools for enhancing their own careers.”

“… meeting someone who loves a painting and wishes to live with it, who wants to learn the details of its creation and is convinced that owning it will enrich his or her life, is the most rewarding experience for an artist.”

Nonetheless, she persevered – “Early in my career,” she writes, “I decided to follow my own course, regardless of the cost.” She did so, even as she realized that, in her profession, “being different was not considered an asset, but a liability.” Though admitting that all artists, including herself, crave recognition, she writes that “meeting someone who loves a painting and wishes to live with it, who wants to learn the details of its creation and is convinced that owning it will enrich his or her life, is the most rewarding experience for an artist.”

To mark her 80th birthday, in 2015, and her 50th year in Canada, Granirer gave many others a gift. “Established galleries usually charge the artist 50% commission for each work sold, in exchange for space and promotion,” she explains. “Why not invite the public … for 10 days and offer the commission to my collectors instead.” It was because of this generosity that I was able to buy my first Granirer.

After this exhibition and sale, Granirer and her husband headed back to Romania, 65 years after they had left the country. It was a meaningful visit with at least three serendipitous occurrences. But, back in Vancouver, she ended up in hospital. Sixteen days later, after two surgeries for diverticulitis, she made it home. “I counted my blessings and told myself how much worse it could have been,” she writes. “What if it had happened while I was in Romania?”

She returns to the memoir’s opening paragraph about getting older, in which she remarks, “Simple words like ‘later,’ ‘next year,’ ‘tomorrow,’ ‘not now,’ become risky, unsure and speculative.” But there is also much to look forward to, she says. At the time of writing, it was an international exhibit in Costa Rica and one in Spain. Currently, she’s preparing for the Zack Gallery exhibit and the launch of the memoir. The event takes place Nov. 16, 6 p.m., and admission is free. It will be a great opportunity to meet the artist – and pick up a copy of Light Within the Shadows.