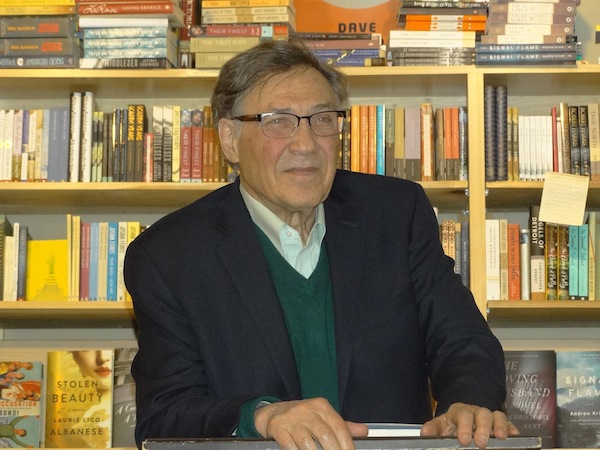

Jack Zipes gives the lecture Resurrecting Dead Fairy Tales on Facebook Feb. 17. (photo from MISCELLANEOUS Productions)

Some fairy tales are timeless in that they still have lessons to impart. For example, The Pied Piper, a story dating back to the Middle Ages, “is a tale of plague, greed, betrayal, conformity/confinement with allusions to child abuse,” explained Elaine Carol, co-founder and artistic director of MISCELLANEOUS Productions.

MISCELLANEOUS’s Plague project will have participating youth, along with professional artists, interpreting the Brothers Grimm’s The Pied Piper “from an intersectional, anti-racist, anti-oppression, queer feminist perspective.” In preparation, Carol told the Independent, “we have been reading our way through the mountain of brilliant writing by Jack Zipes, asking him many questions – even our film editor of Resurrecting Dead Fairy Tales is now reading two of his hundred or more published books.”

Zipes’ recorded Facebook Watch talk, Resurrecting Dead Fairy Tales, will be streamed Feb. 17, followed by a live Q&A with Zipes. Some of the lecture will be part of the documentary being created about the youth-centred theatre project, which will include various workshops and an eventual stage production at the Scotiabank Dance Centre in 2022.

“I have also been working with young professional artists Tiffany Yang, who was a youth in our Monsters production, national and international tours, and Julia Farry, our production assistant/outreach worker,” said Carol. “Tiffany has translated four indigenous Taiwanese folk tales that are stories of plague – mostly in coastal communities, including animal wonder tales of fantastical fishes and other fascinating narratives. Julia has translated three Japanese folk tales focusing on plagues. There are many plague stories that we still hope to collect, including the facts of disease spread by European settlers to the Indigenous people of Turtle Island, as research materials for our project-in-development.

“We are currently collecting these tales to bring to our youth cast after it is deemed safe to work with them in person,” Carol continued, “as we will be using theatre, hip hop/streetdance, contemporary dance, marimba and world music, urban music, performance art, etc., to co-create a new play. This play will be used as a vehicle for the youth to discuss their own experiences of living in a world pandemic.”

Zipes’ lecture was filmed in Minneapolis by MISCELLANEOUS Productions’ professionals. The professor emeritus of German and comparative literature at the University of Minnesota is an expert on folklore and fairy tales. He is a storyteller himself and the founder of the publishing house Little Mole and Honey Bear.

“My parents and grandmother always told me tales of different kinds,” Zipes told the Independent. “When I began studying for a PhD at Columbia University, I wrote my dissertation on ‘The Great Refusal: Studies of the German and American Romantics in the 19th Century.’ My interest in fairy tales grew as I realized that these imaginary tales hold more truth than the so-called realistic future. And I also was angered by Bruno Bettelheim’s book about fairy tales in which he imposed a Freudian interpretation on readers. Since then, I have been trying to reveal how relevant fairy tales are to our lives.”

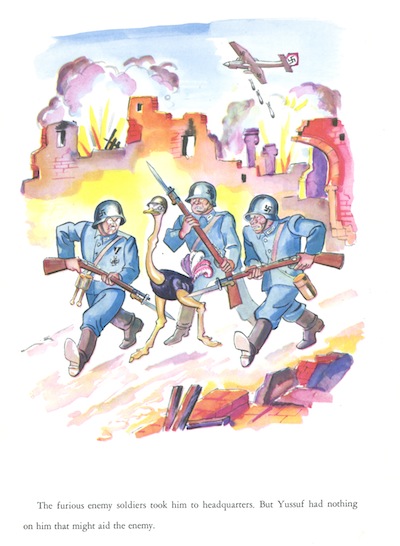

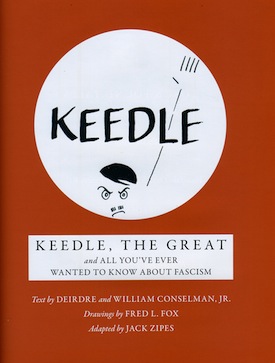

The examples given in the lecture’s press release are from two books Zipes has translated and published: “For example, in Yussuf the Ostrich, well-known political caricaturist Emery Kelen tells the story of a young ostrich who helps defeat the Nazis in northern Africa during World War II. In Keedle, The Great, first published in 1940, Deirdre and William Conselman Jr. sought to give Americans hope that the world can overcome dictatorships. To the authors, the title character Keedle represented more than Hitler, but all dictators then and now.”

Zipes said, “I don’t think that my being Jewish accounts for my interest in fairy tales. My Jewishness makes me a bit meshuggah, and this is why I try to think out of the box and have developed a storytelling program for children without sanitizing the fairy tales. The best of folk and fairy tales have never been sanitized, and I use tales to tell so that children will be enabled to tell their own miraculous tales.”

“My Jewishness is complex,” said Carol, “because I am mixed-race Sephardic-Romani and Ashkenazi. One of one million reasons I love Jack Zipes and think his work is crucial is his lucid critique of the Disneyfication of fairy tales and folklore.”

Resurrecting Dead Fairy Tales starts at 5pm on Feb. 17 and is intended for older youth and adult audiences. On the day and time, click here for link to watch.

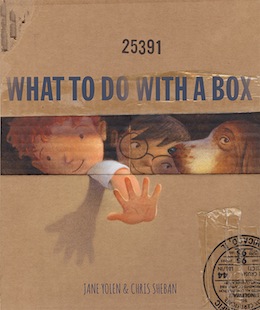

The beautifully and creatively illustrated What to do with a Box (Creative Editions, 2016) features the rhythmic writing of Jane Yolen and the inspired art of Chris Sheban. The book is a tribute to the power of the imagination – a way to impart to the younger set that fun doesn’t necessarily need batteries. It’s also a reminder to parents that expensive toys aren’t at the root of what makes playtime enjoyable, and they may even be enticed to join their kids in a cardboard box adventure – if they’re invited to come along, that is.

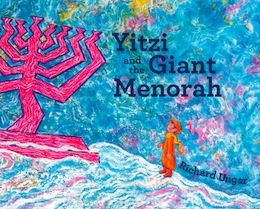

The beautifully and creatively illustrated What to do with a Box (Creative Editions, 2016) features the rhythmic writing of Jane Yolen and the inspired art of Chris Sheban. The book is a tribute to the power of the imagination – a way to impart to the younger set that fun doesn’t necessarily need batteries. It’s also a reminder to parents that expensive toys aren’t at the root of what makes playtime enjoyable, and they may even be enticed to join their kids in a cardboard box adventure – if they’re invited to come along, that is. For slightly older readers (or listeners), Richard Unger has written and illustrated a more traditional story with Chagallesque art, Yitzi and the Giant Menorah (Penguin Random House, 2016). It is a picture book, but with a substantive amount of text on each page. It, too, is beautifully and creatively put together, with most of the text printed on a plain page that includes a black-and-white sketch that doesn’t overlap it in any way, making the reading easier. More importantly, it leaves most of the colorful, vibrant and expressive artwork on the opposite page free from writing. At the end of the book is the brief story of Chanukah.

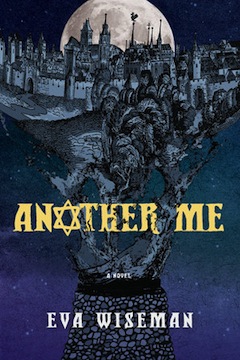

For slightly older readers (or listeners), Richard Unger has written and illustrated a more traditional story with Chagallesque art, Yitzi and the Giant Menorah (Penguin Random House, 2016). It is a picture book, but with a substantive amount of text on each page. It, too, is beautifully and creatively put together, with most of the text printed on a plain page that includes a black-and-white sketch that doesn’t overlap it in any way, making the reading easier. More importantly, it leaves most of the colorful, vibrant and expressive artwork on the opposite page free from writing. At the end of the book is the brief story of Chanukah. Eva Wiseman’s Another Me (Tundra Books, 2016) is set in the mid-1300s in Strasbourg, France. It starts with the main character’s death at the hands of the men poisoning the town’s water – an act the Jews were accused of committing not only in Strasbourg, but other cities in Europe, as well. It was thought that poisoned water was causing the plague and, since fewer Jews were dying, the rumors began that they were causing the illness. In reality, Jews were also dying, but in fewer numbers because Jewish law required much more handwashing than was customary in medieval times.

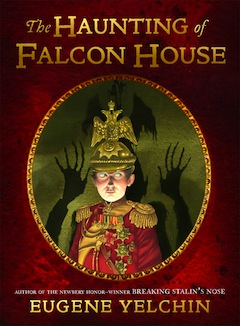

Eva Wiseman’s Another Me (Tundra Books, 2016) is set in the mid-1300s in Strasbourg, France. It starts with the main character’s death at the hands of the men poisoning the town’s water – an act the Jews were accused of committing not only in Strasbourg, but other cities in Europe, as well. It was thought that poisoned water was causing the plague and, since fewer Jews were dying, the rumors began that they were causing the illness. In reality, Jews were also dying, but in fewer numbers because Jewish law required much more handwashing than was customary in medieval times. Magic – or, at least, ghosts – also informs the storytelling in Eugene Yelchin’s The Haunting of Falcon House (Henry Holt and Co., 2016).

Magic – or, at least, ghosts – also informs the storytelling in Eugene Yelchin’s The Haunting of Falcon House (Henry Holt and Co., 2016). Jane Yolen’s Briar Rose: A Novel of the Holocaust (Tor Teen, 2016) is also a retelling – an adaptation of Sleeping Beauty. And, it is a reissue, having originally been published almost 15 years ago in a series created by Terri Windling, which comprised novels by various authors that reinterpreted classic fairy tales.

Jane Yolen’s Briar Rose: A Novel of the Holocaust (Tor Teen, 2016) is also a retelling – an adaptation of Sleeping Beauty. And, it is a reissue, having originally been published almost 15 years ago in a series created by Terri Windling, which comprised novels by various authors that reinterpreted classic fairy tales.