Books can take you to the most captivating places. Not always happy places, but places worth exploring, places where the people, environment, challenges and culture are different. A place you can have adventures, learn from what has happened to others or just escape from your daily routine, all for the relatively low price of a book. Oh, and maybe a cardboard box.

The beautifully and creatively illustrated What to do with a Box (Creative Editions, 2016) features the rhythmic writing of Jane Yolen and the inspired art of Chris Sheban. The book is a tribute to the power of the imagination – a way to impart to the younger set that fun doesn’t necessarily need batteries. It’s also a reminder to parents that expensive toys aren’t at the root of what makes playtime enjoyable, and they may even be enticed to join their kids in a cardboard box adventure – if they’re invited to come along, that is.

The beautifully and creatively illustrated What to do with a Box (Creative Editions, 2016) features the rhythmic writing of Jane Yolen and the inspired art of Chris Sheban. The book is a tribute to the power of the imagination – a way to impart to the younger set that fun doesn’t necessarily need batteries. It’s also a reminder to parents that expensive toys aren’t at the root of what makes playtime enjoyable, and they may even be enticed to join their kids in a cardboard box adventure – if they’re invited to come along, that is.

The writing is simple, as it is for most picture books. That box, “can be a library, palace, or nook,” or a place you can “invite your dolls to come in for tea”; it can be a racecar, a ship, and so much more. And the art by Sheban looks as if he took Yolen’s advice: “You can paint a landscape with sun, sand and sky or crayon an egret that’s flying right by.” It is described as cardboardesque and, indeed, it looks as if he drew the illustrations on different types of boxes.

For slightly older readers (or listeners), Richard Unger has written and illustrated a more traditional story with Chagallesque art, Yitzi and the Giant Menorah (Penguin Random House, 2016). It is a picture book, but with a substantive amount of text on each page. It, too, is beautifully and creatively put together, with most of the text printed on a plain page that includes a black-and-white sketch that doesn’t overlap it in any way, making the reading easier. More importantly, it leaves most of the colorful, vibrant and expressive artwork on the opposite page free from writing. At the end of the book is the brief story of Chanukah.

For slightly older readers (or listeners), Richard Unger has written and illustrated a more traditional story with Chagallesque art, Yitzi and the Giant Menorah (Penguin Random House, 2016). It is a picture book, but with a substantive amount of text on each page. It, too, is beautifully and creatively put together, with most of the text printed on a plain page that includes a black-and-white sketch that doesn’t overlap it in any way, making the reading easier. More importantly, it leaves most of the colorful, vibrant and expressive artwork on the opposite page free from writing. At the end of the book is the brief story of Chanukah.

While set on the eve of Chanukah in the shtetl of Chelm, this tale bears a similar message to What to do with a Box: money isn’t everything. It adds to that the lesson of gratitude.

In the story, the mayor of Lublin gives the people of the Chelm “the biggest menorah” Yitzi has ever seen and the villagers are so grateful, they want to thank the mayor in a way that matches the grandeur of his gift. This being Chelm, the solution doesn’t come easily but, after a few failed efforts, they succeed in a heartwarming way.

* * *

For young adult readers, the stories are much more serious in both subject matter and tone.

Eva Wiseman’s Another Me (Tundra Books, 2016) is set in the mid-1300s in Strasbourg, France. It starts with the main character’s death at the hands of the men poisoning the town’s water – an act the Jews were accused of committing not only in Strasbourg, but other cities in Europe, as well. It was thought that poisoned water was causing the plague and, since fewer Jews were dying, the rumors began that they were causing the illness. In reality, Jews were also dying, but in fewer numbers because Jewish law required much more handwashing than was customary in medieval times.

Eva Wiseman’s Another Me (Tundra Books, 2016) is set in the mid-1300s in Strasbourg, France. It starts with the main character’s death at the hands of the men poisoning the town’s water – an act the Jews were accused of committing not only in Strasbourg, but other cities in Europe, as well. It was thought that poisoned water was causing the plague and, since fewer Jews were dying, the rumors began that they were causing the illness. In reality, Jews were also dying, but in fewer numbers because Jewish law required much more handwashing than was customary in medieval times.

Wiseman also elaborates upon less tangible Jewish beliefs in Another Me. When Natan, 17, dies, his story doesn’t end. He becomes an ibbur – his soul enters the body of another man; in this instance, that of Hans the draper.

Hans works for Wilhelm, with whose daughter, Elena, Natan has fallen in love. Natan has come to know all of these non-Jews from helping his father in the shmatte business. Wilhelm is one of the very few Strasbourgians who is not antisemitic. Hans is also a good person, though he is jealous of Elena’s affection for Natan. When Natan – to whom she’s attracted – becomes Hans – who she finds ugly – Elena struggles to see beyond the exterior.

While mostly told from Natan’s perspective, Wiseman also allows Elena to tell a substantial part of the story. It is sometimes hard as a reader to change gears, but the dual voices offer a deeper understanding of the situation of the Jews in the city (and beyond), and those who would help them. Being historical fiction, while Wiseman can play with magic, there is, sadly, no chance for a happy ending.

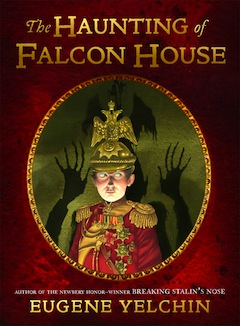

Magic – or, at least, ghosts – also informs the storytelling in Eugene Yelchin’s The Haunting of Falcon House (Henry Holt and Co., 2016).

Magic – or, at least, ghosts – also informs the storytelling in Eugene Yelchin’s The Haunting of Falcon House (Henry Holt and Co., 2016).

Ostensibly, this book is a translation Yelchin has made from a bundle of decaying pages bound with twine that he came across as a schoolboy in Russia. He brought them with him when he immigrated to the United States, but let them sit for years. Apparently written and illustrated by “a young Russian nobleman, Prince Lev Lvov,” who was born in 1879, there were many pages missing or unreadable.

“I managed to establish a chronological order of the events and then divided them into chapters, matched the drawings to the chapters, and discarded those I could not match,” writes Yelchin in the translator’s note that begins the book. So “inwardly connected to the young prince” did Yelchin become, he writes, “I can’t be certain, but as I typed Prince Lev’s inner thoughts, I felt cool fingers firmly guiding mine across the keys.”

In the story, 12-year-old Lev’s hands are similarly guided by a mysterious force when he is drawing. Arriving at Falcon House from St. Petersburg to take his place as heir to his family’s estate, Lev – who bears a striking resemblance to his grandfather – dreams of being a hero and nobleman like his grandfather and preceding ancestors. But, with some mystical guidance from Falcon House’s resident ghost, Lev begins to understand that being nobility doesn’t necessarily mean being noble, and his family’s secrets, which are slowly revealed, make him rethink his aspirations.

The ghost, a scary aunt and the disturbing illustrations combine to good effect in The Haunting of Falcon House, even though the story takes a little too long to unfold. The detailed notes at the book’s end provide valuable historical context and add greatly to the reading experience.

Jane Yolen’s Briar Rose: A Novel of the Holocaust (Tor Teen, 2016) is also a retelling – an adaptation of Sleeping Beauty. And, it is a reissue, having originally been published almost 15 years ago in a series created by Terri Windling, which comprised novels by various authors that reinterpreted classic fairy tales.

Jane Yolen’s Briar Rose: A Novel of the Holocaust (Tor Teen, 2016) is also a retelling – an adaptation of Sleeping Beauty. And, it is a reissue, having originally been published almost 15 years ago in a series created by Terri Windling, which comprised novels by various authors that reinterpreted classic fairy tales.

In Yolen’s reimagining, Briar Rose (aka Sleeping Beauty) is Gemma, Rebecca’s grandmother. Unlike her cynical and competitive older sisters, Rebecca never tires of listening to Gemma’s version of the tale, which doesn’t quite match up with the traditional folktale. When Gemma dies, leaving behind a box containing a few documents and photos that don’t quite match up with what she has told her family about her history, Becca sets off to find the truth.

Her search – done in the days before Google – starts slowly, with the help of her editor, Stan, on whom she has a crush. It takes them from their hometown of Holyoke, Mass., to Oswego, N.Y., where refugees were sheltered at Fort Oswego: “Roosevelt made it a camp and, in August 1944, some 1,000 people were brought over and interned [there]. From Naples, Italy. Mostly Jews and about 100 Christians,” explains the reporter at the Palladium Times to Becca.

What she learns at Oswego leads her on a journey to Poland and to Chelmno. Of the more than 152,000 killed by gas (or shooting) at the Nazi extermination camp that was there, only seven Jewish men are known to have escaped. This allows Yolen to imagine that one woman survived the killing centre, which was established on an old estate in a forest clearing that had a schloss (castle, or manor house).

In Gemma’s cryptic telling of her survival, she is saved from the castle by a “prince,” who we find out was himself saved by partisans after his escape from Sachsenhausen concentration camp and then joined the resistance; in her story, briars take the place of barbed wire, the wicked fairy the Nazis. As Becca discovers the reality of her grandmother’s past and finds her own voice and identity through the journey, we also witness Poles’ difficulties in dealing with what took place during the Holocaust and we meet others – including Gemma’s prince – who are still trying to heal from the destruction the Nazis’ wrought.

Interweaving the “real” story with Gemma’s fairy tale is very effective at building the anticipation and, once Becca arrives in Poland, Briar Rose is a page-turner. One almost doesn’t realize how much they’re learning while they’re reading. Almost.