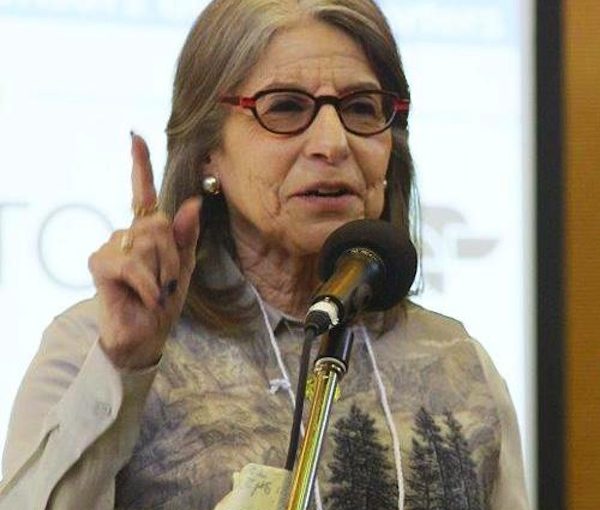

Prof. Norma Joseph (photo from Association for Canadian Jewish Studies)

On June 2, the Association for Canadian Jewish Studies is holding a day of lectures in the Jewish community that will be topped off with music from the Vancouver Jewish Folk Choir, the granting of the 2019 Louis Rosenberg Canadian Jewish Studies Distinguished Service Award to scholar and activist Norma Joseph and a talk by Franklin Bialystok on Canadian Jewish Congress.

“We offer a community day every year, and it’s always the opening day of the conference,” co-organizer Jesse Toufexis told the Independent.

“The motivations for the community day are plentiful,” said Toufexis. “Firstly, we receive great support in a number of ways from Jewish communities all over Canada, so this is an excellent way not only to thank them but to show them what the scholarly community is up to.

“Secondly, the Jewish community is interested in the topics we cover, from history to sociology to literature and art. So, coming from fields where we work on such minutely detailed projects, it’s fun to engage with a community that gets excited about the topics we ourselves find exciting.

“Thirdly, I think holding a community day is just part of a tradition that fosters togetherness. We aren’t scholars out in the ether, doing our own thing and keeping it to ourselves. I think of us more as a branch of a much larger Canadian Jewish community that includes all the various roles and aspects of Jewish life in this country, and I think it’s something of a duty to share what we’re constantly learning about our common past, present and future.”

Prof. Rebecca Margolis, ACJS president, praised Toufexis and co-organizer Prof. Richard Menkis on having “put together an amazing community day together in partnership with a team of local organizations that have gone above and beyond to make this day a success: Jewish Museum and Archives of B.C. and our host, the Peretz Centre for Secular Jewish Culture. As a member-run organization,” she said, “we value opportunities to collaborate with local organizations in order to produce exciting programming on the Jewish Canadian experience.”

The first panel session of the day is Jewish Space in Literature and Popular Culture, followed by Antisemitism and the Holocaust. At lunch, a panel discusses the topic Archives Matter. The two afternoon panels are Media Studies, and Challenging the Status Quo. Joseph’s talk in this last session is called No Longer Silent: Iraqi Jewish Immigrants and the CJC.

“I’ve been working on the Iraqi Jewish community in a bunch of different ways and my most recent publications are about their food and what we can learn about their cultural history and immigration patterns through studying their food,” Joseph told the Independent in a phone interview from her home in Montreal. “But I’ve also looked at, through the immigration pattern, the traumas they suffered by the expulsion from Iraq and the processes through which they had to escape from Iraq, as well as the ways in which they adapted to life in Montreal.”

It is only in the last decade or two, said Joseph, that Iraqi Jewish community members have “begun to present their memoirs and talk about how awful the experience from the Farhud in 1941 was. So, then I began to gather their stories.”

Joseph is particularly interested in the transition of the community from being unwilling to talk about their experiences to talking about them. “And also,” she said, “in the process of [preparing for] this year’s conference, which is celebrating 100 years of Canadian Jewish Congress, to figure out in what ways did Canadian Jewish Congress help or not help this community migrate or emigrate into Canada, which was, in fact, to Montreal. And that’s where I’m doing research right now. The Iraqi Jews themselves say, oh no, they didn’t help us … we came alone, we found our way on our own and nobody ever helped us. We didn’t ask for help. We weren’t refugees…. End of story.”

This perspective, as well as the larger Jewish community’s focus at the time on dealing with the impacts of the Holocaust, contributed to the silence, said Joseph.

“I wanted to go behind the scenes and say, OK, but in what ways that they [Iraqi Jews] might not have known was Congress working with the Government of Canada to open the doors, because we know that the doors of Canada were closed to Jewish immigration during World War Two but, afterwards, in the 1950s the doors open…. Did anyone in Congress help Middle Eastern Jews come? That’s my question. And that’s what I’m researching now at the archives, interviewing some people.”

Joseph’s interest in the Iraqi Jewish community comes in part from her and her husband Howard’s experiences.

“In 1970,” she said, “we came to Canada [from the United States]. He was invited to become the rabbi of the Spanish and Portuguese congregation. He was their rabbi for 40 years. And the congregation has many different communities – it has Iraqis, Lebanese, Moroccan, some Iranians, and we love the diversity of communities, the cultural diversity was so exciting.

“I never thought of studying the communities that we were friendly with and that my husband was the rabbi of, but, eventually, at some point, somebody said to me, why don’t you study Canadian Jews? And I looked around me at all these wonderful, diverse ethnic communities of Jews and I said, oh, this is a great idea, why not study the people I know so well?

“And I was interested in gender. I started asking a lot of questions and I especially focused on the women. And it came out that they were willing to talk to me, especially about food, and food was an entree into learning about their experiences, both in Baghdad and the transitions to Montreal and how hard those transitions were…. They couldn’t find the right foods and they didn’t know how to cook and there were no cookbooks and how were they going to cook and where were they going to find the spices? That was very symbolic of life, the difficulties of life in Montreal for this community that didn’t like gefilte fish.”

Joseph is being honoured by the ACJS for attaining the “highest standards of scholarship, creative and effective dissemination of research, and activism in a manner without rival in our field of Canadian Jewish studies, as well as being a respected voice in Jewish feminist studies more broadly.” Not only is she being recognized for “her mastery of both traditional rabbinic sources and anthropological methods,” but her teaching, her work in documentary and educational film, being a founding member of the Canadian Coalition of Jewish Women for the Get, as well as participating in the founding of the Institute for Canadian Jewish Studies at Concordia University, among many other accomplishments. For more than 15 years, she has written a regular column in the Canadian Jewish News. In one of these columns, in recent months, she recalled a time “when the phrase ‘liberal values’ was not a dirty word.”

“I was raised Orthodox,” she told the Independent. “My grandfather was a great Orthodox rabbi in Williamsburg…. But my parents worked very, very hard to send me to one of the great liberal Orthodox schools. It was called the Yeshivah of Flatbush, where boys and girls study together and we were taught that boys and girls could learn, and girls were included in that equation. It was one of the best schools because I learned fluent Hebrew, which was very rare, and it was a Zionist school, beginning in the ’50s.”

She added, “It wasn’t our liberal values in the 21st century, but it was mid-20th-century values. We learned to love Israel. We learned about justice, we learned about equality in some very interesting ways. We were patriotic Americans, my country right or wrong, which, after Vietnam, we had to rejig, but we were there before Vietnam…. I’ll tell you another thing that’s interesting about my upbringing – we didn’t learn about the Holocaust. At that age, in the ’50s and ’60s, parents didn’t want their children traumatized by stories of the Holocaust.”

Between her own studies of Jewish law and those of her husband, Joseph lauded the insight and flexibility that can be found in Judaism. “My husband always taught me that, if you are a legalist, are in charge of the law … the easiest answer is no, because it means you don’t have to examine and search the law. The hardest thing, but most creative thing, is to find a way to say yes…. We have thousands of years of law – surely in all that precedent you can find something.”

As but one example, Joseph has used Jewish law to argue for the rights (and obligations) of women, and has seen progress on the feminist front.

“For example,” she said, “let’s just take the world of bat mitzvah. In the 1950s, there weren’t bat mitzvahs, for the most part. Even the Conservative and Reform movements didn’t want bat mitzvahs…. Today, 2019, there isn’t a community that doesn’t offer some form of recognition of a girl’s 12th birthday,” including Chassidic communities.

“That’s a transformation because of feminist critique,” she said. “They will never admit it. They will say we always did it. But that’s a big change, on one hand. On the other hand, it’s silly, it’s narishkeit; it’s small, it’s nothing.”

But even incremental change leads to larger change, and Joseph spoke about the “incredible historical research coming out – women [always] had strong ritual lives, but what’s coming out now is the need for public ritual formats for women in all sectors of society.”

For the full schedule of and to register for the ACJS community day, visit eventbrite.ca.