Here’s a scenario to consider: What if Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu came to the Knesset with a peace accord, approved by all its neighbors, that provided for the cessation of war, the recognition of the state of Israel, land swaps to create coherent borders and the dismantling of settlements?

What if Netanyahu said the final decision on the agreement would be up to the Knesset and he would remain on the sidelines, campaigning neither for nor against the agreement? Would the Knesset endorse the deal?

At first blush, such a scenario sounds farfetched, it could never happen. But, 35 years ago, that is exactly what occurred.

Former prime minister Menachem Begin came to the Knesset with a peace agreement with Egypt. He was reluctant to abandon settlements in the Sinai, but he let members of the Knesset vote on the agreement and did not campaign against it. They endorsed the deal.

The 1979 Camp David Accords proved to be more durable than many expected, surviving the assassination of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat, the Lebanon war, the Gaza conflicts and the Arab Spring. Also, the accord laid the foundation for an agreement with Jordan that is now marking its 20th anniversary.

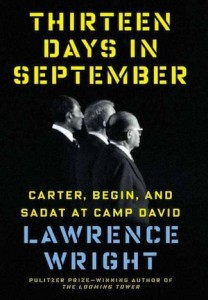

In Thirteen Days in September: Carter, Begin and Sadat at Camp David (Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), New Yorker staff writer and Pulitzer Prize-winner Lawrence Wright goes back to the difficult negotiations in September 1978 that led to the reluctant handshake between Sadat and Begin, and the signing of the accord on the White House lawn in March 1979.

In Thirteen Days in September: Carter, Begin and Sadat at Camp David (Alfred A. Knopf, 2014), New Yorker staff writer and Pulitzer Prize-winner Lawrence Wright goes back to the difficult negotiations in September 1978 that led to the reluctant handshake between Sadat and Begin, and the signing of the accord on the White House lawn in March 1979.

U.S. president Jimmy Carter brought the Egyptian president and the Israeli prime minister together after Sadat took the first courageous step toward peace – a visit to Jerusalem in 1977. The three leaders and some of their most senior aides met at Camp David, a secluded country retreat about 100 kilometres outside Washington, D.C. They stayed for almost two weeks, stepping away from the whirlwind of day-to-day events to focus exclusively on a framework for peace.

A playwright and screenwriter, Wright effectively recreates the moments of high drama during the talks, weaving personal histories, sacred mythologies and past events into a detailed account of the bare-knuckle bargaining session. He also fleshes out the secondary characters, the members of the Israeli, Egyptian and U.S. bargaining teams who played a role in reaching an agreement. In the acknowledgements, Wright says he initially wrote a play about the negotiation, but he could not squeeze all the interesting characters into a 90-minute play.

The evocative portrayal of Moshe Dayan – the Israeli-born warrior who came to personify the country’s most spectacular military accomplishment in 1967 as well as its most significant loss in 1973 – is especially memorable. Dayan is described alternately as a cold-blooded, calculating fighter and the government’s most creative thinker in pursuit of peace.

The book offers a rare glimpse inside the world of high-pressure international negotiations and sheds light on the difficult relationship that Carter continues to have with Israel. That alone would make the book worthwhile. Yet Thirteen Days is more than just an historical account. Delving into how the Camp David Accords were reached inevitably fires up the imagination to think about what is possible.

Could these achievements ever be repeated again?

Wright shines a spotlight on some extraordinary aspects of the negotiations. The U.S. president, who was prepared to dedicate an inordinate amount of time to grappling with the competing interests in the Middle East, had come to the table with little more than a biblical understanding of the issues and virtually no experience in foreign policy. Yet, he shared with the Egyptian president a similar upbringing, religious devotion and commitment to service in the military. An easy rapport evolved between the two men.

Carter had a more difficult time finding a personal connection with Begin, who was scarred by the Holocaust and hardened by his experiences fighting British authorities in Palestine before the establishment of the state.

The isolation of Camp David allowed negotiators to work creatively and take risks that might not have been ventured in the public eye, Wright writes. But being forced together also had negative consequences. The intimacy at times fed hostility, rather than creating trust, and almost torpedoed the talks.

The process of negotiating, ridded with cultural misunderstandings and political miscalculations, was particularly challenging. Sadat and Begin had significantly different approaches to the talks. Sadat came with an agenda of unrealistic demands, but was willing to compromise. Begin came to listen and react. For several days, he adamantly refused to concede anything.

In his naïveté, Carter expected the two warring sides to reach an accord on their own. His opening gambit was to just bring the two sides together and step back. He assumed they would resolve their historic differences once they met and shared their history, their suffering and their dreams. How wrong he was.

Their response at critical moments was a study in contrasts. Where Sadat, a visionary, would become emotional when his idealism was challenged, Begin would become colder and more analytical. Begin kept his eye on details, meticulously dissecting every nuance in anticipation of what could be lurking around the corner. “Both desired peace,” recalled Ezer Weizman, who was Israel’s defence minister at the time. “But Sadat wanted to take it by storm and Begin preferred to creep forward inch by inch.”

Carter eventually realized he had to take the lead. But it was not until the sixth day of negotiations that he introduced a framework for peace that was to be the springboard for negotiated compromises and a final deal.

Despite the hurdles, somewhere there was magic. They reached an agreement.

Wright suggests that domestic political considerations played a significant role. The political cost for all three leaders increased as the negotiations stretched on. Carter, who staked his reputation on bringing the conflict to an end, threatened to break relations with Sadat or Begin if either leader walked away. The threats kept the two wily politicians at the table, despite their personal animosities.

Another pivotal issue was how the three leaders responded to matters related to the Palestinians. Sadat was their self-appointed representative at the talks. But, at a crucial moment, he pushed their interests aside. It was a decision that cost him his life. At the time, however, the prospect of regaining full sovereignty over the Sinai Peninsula was just too tantalizing; leaving the Palestinians on the sidelines enabled the accords to be signed.

Wright observes that there has not been a single violation of the terms of agreement, but he leaves the impression that the Camp David Accords offer little to guide those now searching for more peace. The accords have saved lives and defused tensions in a volatile neighborhood, but the agreement appears to be a unique set of circumstances in history at a time of powerful personalities that probably will not be replicated in our times.

Media consultant Robert Matas, a former Globe and Mail journalist, still reads books. Thirteen Days in September is available at the Isaac Waldman Jewish Public Library. To reserve it, or any other book, call 604-257-5181 or email library@jccgv.bc.ca. To view the catalogue, visit jccgv.com and click on Isaac Waldman Library.