“I am now face to face with dying, but I am not finished with living,” writes Oliver Sacks as the dedication to Gratitude (Knopf Canada, 2015), a collection of four essays that were written in the two years preceding his death last August.

“I have given much of my life to the Jewish world, and I wish I had many more years to serve this noble calling,” writes Edgar Bronfman in concluding his book Why Be Jewish? A Testament (Signal, 2016), which he completed mere weeks before his death in December 2013.

Bronfman continues, “But everything has its natural end, and so now, as my time on earth draws to a close, I would thank my stars even more if you would choose to stand at Sinai; if you would choose, as I did so many years ago, to join this remarkable people who generation after generation held fast to the dream that through our individual and collective efforts we could transform the troubled world we share into a more perfect, more humane, more civilized place.”

Even though he became intrigued with Judaism late in life, Bronfman still defined himself as secular, “not comfortable” calling himself an atheist “in the face of the complexity of the universe.” He had a connection to Judaism through his grandfather, but it was weak. “My parents,” he writes, “for whatever reason, failed to instil much-needed Jewish pride in their children.”

Sacks was a self-described atheist. For him, it was his mother’s strongly negative reaction to the news of his homosexuality that pushed him away from belief: “The matter was never mentioned again, but her harsh words made me hate religion’s capacity for bigotry and cruelty,” he writes.

However, the final essay in Sacks’ Gratitude is called “Sabbath.” In it, he recalls his parents’ observance of Shabbat, a day that “was entirely different from the rest of the week.” He recalls how the family would mark the day, how he became bar mitzvah, his break with his family and community in England after he qualified as a doctor and moved to Los Angeles, his “near-suicidal addiction to amphetamines,” his recovery and how he “became a storyteller at a time when medical narrative was almost extinct.” In addition to being a neurologist, most readers know, Sacks was an author – he wrote more than a dozen books, including Awakenings, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and other Clinical Tales and An Anthropologist on Mars.

However, the final essay in Sacks’ Gratitude is called “Sabbath.” In it, he recalls his parents’ observance of Shabbat, a day that “was entirely different from the rest of the week.” He recalls how the family would mark the day, how he became bar mitzvah, his break with his family and community in England after he qualified as a doctor and moved to Los Angeles, his “near-suicidal addiction to amphetamines,” his recovery and how he “became a storyteller at a time when medical narrative was almost extinct.” In addition to being a neurologist, most readers know, Sacks was an author – he wrote more than a dozen books, including Awakenings, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and other Clinical Tales and An Anthropologist on Mars.

Sacks comes to appreciate Shabbat: “And now, weak, short of breath, my once-firm muscles melted away by cancer, I find my thoughts, increasingly, not on the supernatural or spiritual but on what is meant by living a good and worthwhile life – achieving a sense of peace within oneself. I find my thoughts drifting to the Sabbath, the day of rest, the seventh day of the week, and perhaps the seventh day of one’s life as well, when one can feel that one’s work is done, and one may, in good conscience, rest.”

Gratitude is a short but powerful collection. It is masterfully written and nearly impossible to get through without crying. All of the essays have been published before, but having them together for re-reading, rethinking and re-feeling is more than worthwhile. Every read will be a cathartic experience.

The first essay, “Mercury,” was written just before Sacks’ 80th birthday in July 2013. In it, he talks about what it feels like to be turning 80, some of his regrets, but mostly how much he has left to do, “freed from the factitious urgencies of earlier days, free to explore whatever I wish, and to bind the thoughts and feelings of a lifetime together.”

“My Own Life” is named after the autobiography of one of Sacks’ favorite philosophers, David Hume. Sacks shares a couple of paragraphs from that 1776 work, using it to lead into a discussion of his own state of mind. “My generation is on the way out, and each death I have felt as an abruption, a tearing away of part of myself.” While not without fear, he writes, “my predominant feeling is one of gratitude. I have loved and been loved; I have been given much and I have given something in return; I have read and traveled and thought and written.”

In the third of the four essays, “My Periodic Table,” Sacks talks of his love of the physical sciences and how, since “death is no longer an abstract concept, but a presence,” he is surrounding himself again, as he did when he was a boy, “with metals and minerals, little emblems of eternity.” On his writing table is a gift from friends for his 81st birthday, thallium, as well as lead, for his recently celebrated 82nd birthday. After discussing the treatment of his cancer, he expresses his skepticism about reaching 83, his bismuth birthday. He did, indeed, pass away at 82.

Bronfman died at 84. It is particularly fitting to be discussing his book Why Be Jewish? as Passover nears. Two of the nine chapters are directly related to the holiday: Chapter 8 is about its rituals, the story, the symbolic aspects, its importance, while Chapter 9 presents the principles and practices of leadership as demonstrated by Moses – not Moses the manager, but rather, “Moses the man who, as flawed as he was, executed brilliant strategies that ultimately transformed much of the world. These principles are also relevant to everyday leadership, from parenting to day-to-day responsibilities at work.”

Bronfman died at 84. It is particularly fitting to be discussing his book Why Be Jewish? as Passover nears. Two of the nine chapters are directly related to the holiday: Chapter 8 is about its rituals, the story, the symbolic aspects, its importance, while Chapter 9 presents the principles and practices of leadership as demonstrated by Moses – not Moses the manager, but rather, “Moses the man who, as flawed as he was, executed brilliant strategies that ultimately transformed much of the world. These principles are also relevant to everyday leadership, from parenting to day-to-day responsibilities at work.”

There are many lessons Bronfman derives from Moses and the Exodus story. Good leadership involves standing up for something, perseverance, vision, pragmatism, courage, celebration of accomplishment, allowing opinions (even complaints, perhaps especially complaints), awareness of one’s strengths and shortcomings, adherence to a moral code, the duty to pass the mantle. He doesn’t believe that Moses’ non-admittance into the Promised Land was a punishment – instead, from Mount Nebo, Moses is permitted to see the entire Promised Land, “God is showing Moses the future that is really what most leaders want: they want to know that their dreams and vision will live on.”

Bronfman notes about the Torah’s last word, Israel: “It seems to me that we are being told that the commitment to Israel – the people – must be the focus, not Moses. And since ‘Israel’ means wrestling with God, the Torah also seems to charge the Jewish people with the task of ‘wrestling,’ a term I take to mean a commitment to struggling with that which we find difficult to embrace and not letting go until we find the truths we seek.”

In another chapter – on the rest of the Jewish holidays – Bronfman writes that he “would like to see the institution of Yom Ha’atzmaut Circles in synagogues and communities where Jews of multiple views could come together to discuss books that put forth different ideas on Israel’s situation, from Alan Dershowitz’s The Case for Israel to David Grossman’s novel To the End of the Land.”

He also talks of Shabbat, referring to the group Reboot, “a network of young, creative Jews who have sought ways to grapple with questions of Jewish identity and community in terms that will be meaningful to their generation….” He gives examples of other youth who are engaged in a meaningful Jewish life and the book’s foreword is written by Angela Warnick Buchdahl, who was a Bronfman Fellow in Israel in 1989. The program for high school juniors was founded by Bronfman, former chief executive officer of Seagram Co. Ltd., who also was chair of the board of governors of Hillel International and president of World Jewish Congress. Bronfman has written other books, including The Bronfman Haggadah with his wife, artist Jan Aronson.

The goal of Why Be Jewish? is to encourage nonreligious Jews – especially the younger generation – to practise the elements of Judaism that speak to them, and it is written to that audience. He touches upon all the basics of Judaism from the perspective that, “Judaism does not demand belief. Instead, it asks us to practise intense behaviors whose purpose is to perfect ourselves and the world.”

Bronfman’s approach is appealing in many ways, and he offers practical advice for the non-observant on how to connect with Judaism’s tenets and traditions. Even for the somewhat-observant Jew, many of his ideas will be interesting. His outlook is positive and well conceived. It is also inclusive.

He writes, “My own feeling is that Judaism is a big family of individuals with a common bond that has stayed strong through a long history and much hardship. Those who want to become part of this story are Jews, too. I believe the tent should be open and welcoming to anyone who wishes to join.

“For younger Jews today, choosing a particular ethnicity or culture may seem too narrow a form of self-identification. But I do not see Judaism as a form of tribalism that divides rather than unites. The Jewish people are one of the many vibrant patches on the richly diverse quilt of humanity. Each patch has its own design and, together, they make a beautiful whole. Embracing your heritage deepens your understanding of who you are and where you come from and brings you into a more meaningful relationship with the multicultural world.”

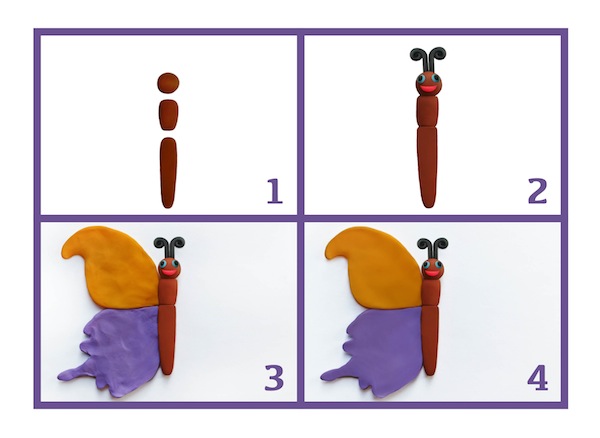

1. Take brown Plasticine and make the butterfly’s head, thorax (torso) and abdomen.

1. Take brown Plasticine and make the butterfly’s head, thorax (torso) and abdomen. 5. Now make and attach identical wings to the right top and bottom sides. Make them smooth, too.

5. Now make and attach identical wings to the right top and bottom sides. Make them smooth, too. However, the final essay in Sacks’ Gratitude is called “Sabbath.” In it, he recalls his parents’ observance of Shabbat, a day that “was entirely different from the rest of the week.” He recalls how the family would mark the day, how he became bar mitzvah, his break with his family and community in England after he qualified as a doctor and moved to Los Angeles, his “near-suicidal addiction to amphetamines,” his recovery and how he “became a storyteller at a time when medical narrative was almost extinct.” In addition to being a neurologist, most readers know, Sacks was an author – he wrote more than a dozen books, including Awakenings, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and other Clinical Tales and An Anthropologist on Mars.

However, the final essay in Sacks’ Gratitude is called “Sabbath.” In it, he recalls his parents’ observance of Shabbat, a day that “was entirely different from the rest of the week.” He recalls how the family would mark the day, how he became bar mitzvah, his break with his family and community in England after he qualified as a doctor and moved to Los Angeles, his “near-suicidal addiction to amphetamines,” his recovery and how he “became a storyteller at a time when medical narrative was almost extinct.” In addition to being a neurologist, most readers know, Sacks was an author – he wrote more than a dozen books, including Awakenings, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and other Clinical Tales and An Anthropologist on Mars. Bronfman died at 84. It is particularly fitting to be discussing his book Why Be Jewish? as Passover nears. Two of the nine chapters are directly related to the holiday: Chapter 8 is about its rituals, the story, the symbolic aspects, its importance, while Chapter 9 presents the principles and practices of leadership as demonstrated by Moses – not Moses the manager, but rather, “Moses the man who, as flawed as he was, executed brilliant strategies that ultimately transformed much of the world. These principles are also relevant to everyday leadership, from parenting to day-to-day responsibilities at work.”

Bronfman died at 84. It is particularly fitting to be discussing his book Why Be Jewish? as Passover nears. Two of the nine chapters are directly related to the holiday: Chapter 8 is about its rituals, the story, the symbolic aspects, its importance, while Chapter 9 presents the principles and practices of leadership as demonstrated by Moses – not Moses the manager, but rather, “Moses the man who, as flawed as he was, executed brilliant strategies that ultimately transformed much of the world. These principles are also relevant to everyday leadership, from parenting to day-to-day responsibilities at work.”