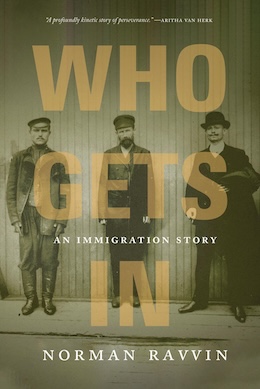

Author Norman Ravvin’s grandparents, Yehuda Yoseph and Chaya Dina Eisenstein, around the time of their engagement, in 1928. (photo from Who Gets In: An Immigration Story)

Relentless perseverance, continual pressure on select politicians and some key allies are what helped Norman Ravvin’s maternal grandfather, Yehuda Yoseph Eisenstein, finally bring his wife and two children to Canada from Poland in 1935, five years after he immigrated here. In a decade generalized as a time of “none is too many” with regards to Canada’s immigration policy towards Jews, Ravvin’s grandfather managed to get his family into the country.

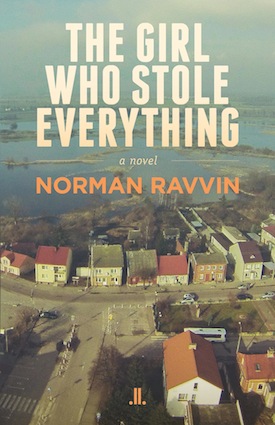

In his new book, Who Gets In: An Immigration Story (University of Regina Press), Ravvin combines his novel-writing skills with his academic expertise to create an engaging memoir about his grandfather’s first years in Canada, one that is firmly situated in the larger context of what was happening at the national level at the time. An extensively researched book – with 10-and-a-half pages of sources – Ravvin’s style will make readers feel like they’ve come to know him a bit, as he allows his personality to be seen in the telling, though what is documented fact and what is conjecture or opinion is clear.

“My approach is to make nothing up. The story rides its own hard-to-believe rails,” says Ravvin on his webpage. “I present its narrative creatively, so readers relate to it on a personal level. Events and personalities from nearly a century ago remain fresh, telling and relevant to contemporary North American life.”

Ravvin does allow his imagination some space. He doesn’t know, for example, the exact reasons his grandfather left Poland, but he can surmise that rising antisemitism was one of them. Whether it was because his grandfather objected physically and publicly to a slur and became a marked man, or whether a rock was thrown into the family’s sukkah, Yehuda Yoseph Eisenstein’s response, writes Ravvin, “was to say ‘I can’t live with these people anymore.’ Or, as he would have said in Yiddish, ‘Ich ken mit zei mer nisht lebn.’ It’s good to hear some of these things in the language in which they took place. In this incident, the spoken words evoke the moment of decision with clarity and purpose.”

Eisenstein had three siblings who had already left Poland, with his younger brother Israel (Izzy) having settled in Vancouver. It was this brother who offered Eisenstein sponsorship and, while Canada was a much less welcoming place by 1930, “a single man could obtain a visa with a brother’s sponsorship.” The problem was Eisenstein had been married in 1928, without a civil licence, as he was already planning on leaving and knew that he would need to appear single to get into Canada. The illegality of the marriage and the misrepresentation of his marital status on his immigration application would cause Eisenstein much tsuris (distress) in getting his wife, Chaya Dina, and their children, Berel and Henna, to Canada as well.

Who Gets In is divided into two parts. The first is about Eisenstein finding his place in the country; the second is about his efforts to bring his family over. Ravvin wants to “paint a detailed picture of the time and place, with careful attention to Western Canada,” where his grandfather went, and he does this by talking about such things as the content of school history books in the 1920s, Canada’s immigration numbers and the country’s changing demographics, the implications of government forms that asked immigrants to declare their “Nationality” and “Race or People,” how census data were being interpreted and used, the popularity of eugenics in Canada and beyond, the impacts of the Depression, and so much more.

Who Gets In is divided into two parts. The first is about Eisenstein finding his place in the country; the second is about his efforts to bring his family over. Ravvin wants to “paint a detailed picture of the time and place, with careful attention to Western Canada,” where his grandfather went, and he does this by talking about such things as the content of school history books in the 1920s, Canada’s immigration numbers and the country’s changing demographics, the implications of government forms that asked immigrants to declare their “Nationality” and “Race or People,” how census data were being interpreted and used, the popularity of eugenics in Canada and beyond, the impacts of the Depression, and so much more.

Ravvin uses history not only to provide context for his grandfather’s experiences but also brings it into the present. Assimilability was a key consideration in assessing immigrants’ suitability in Eisenstein’s day and continues to be – current NDP leader Jagmeet Singh “was approached while campaigning and told that he should remove his turban to look more Canadian,” notes Ravvin.

Ravvin spends quite a lot of ink discussing various perceptions of what a Canadian should like and contemplating how his grandfather would have been considered. The cover of Who Gets In features a photo that was part of a newspaper article in 1910. The three men “appear as cutouts in a group of twelve ‘Types’ of ‘New-Comers’ from ‘Photographs Taken at Quebec and Halifax.’” From left to right, they are described as “Pure Russian, Jew, German.” As the landing form stripped Ravvin’s grandfather of his nationality – someone crossed out the typed letters “PO” and wrote in by hand “Hebrew” – so too is the Jew in this photograph stripped of his, observes Ravvin.

In setting the scene for Part 2 of the book – the bureaucratic fight his grandfather must undertake – Ravvin discusses the Indigenous peoples that inhabited the Prairies where his grandfather ended up. Eisenstein first went to Vancouver, where he hoped to stay and work as a shoichet (kosher butcher), but he was apparently seen as competition by Rev. N.M. Pastinsky, “who happened to be on the board of the Pacific Division of the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society (JIAS) and thus someone with whom one might not want to tangle.”

Eisenstein backtracked to Saskatchewan, living first in the farming town of Dysart and then in Hirsch. Ravvin talks about what Jewish life in rural Canada was like and some of the impacts that European settlement had on the Cree, Saulteaux and Assiniboine.

Ravvin starts the book with the story of the Komagata Maru – the chartered ship from India, full of immigrant hopefuls, mostly Sikhs, that was not allowed to land on the coast of British Columbia in 1914 and was instead forced to return to India, with disastrous results. He returns to the incident at the end of Part 1 to point out that one of the central (negative) figures in his grandfather’s life was A.L. Jolliffe, “who began his civil career in 1913 as an immigration agent in Vancouver,” playing a role in the handling of the Komagata Maru.

“By the 1930s,” writes Ravvin, “Jolliffe had ascended to the position of commissioner for the Department of Immigration in Ottawa. He is the closest thing to a bête noire in my grandfather’s story. If the much better-known doorkeeper, F.C. Blair, played any role in my grandfather’s struggle, he left no trace in any of the documents beyond a shared penchant for the use of pompous and hectoring language that appears in letters in my grandfather’s file.”

Jolliffe denies more than once Eisenstein’s applications for permission to bring his wife and children to Canada – in one instance, while expressly not recommending deportation, Jolliffe suggests that, if Eisenstein wants to be reunited with his family, he should return to Poland. Ultimately, Eisenstein is successful only because he has allies such as A.J. Paull, executive director of the JIAS, and Lillian Freiman who, married to influential merchant A.J. Freiman, had “remarkable access to the leaders of early-twentieth-century Canada.” She also did many amazing good works, including managing “Ottawa’s response to the flu epidemic in 1918 almost single-handedly.” Ravvin also positively differentiates the federal government, as led by R.B. Bennett, prime minister from 1930 to 1935, from that which succeeded it, the “none is too many” government led by William Lyon Mackenzie King as prime minister.

Eisenstein finally achieves his goal through an order-in-council – a decision made by the Privy Council, the prime minister’s cabinet – that “asserted its right to ‘waive’ determinations of an earlier order in which strict immigration regulations were brought into effect. This reflected an ability – understood to exist by those in the know – of the minister to ‘issue a permit in writing to authorize a person to enter Canada without being subject to the provisions’ of the Immigration Act, without interfering with the status of those provisions.”

The Eisenstein family was one of the lucky ones.