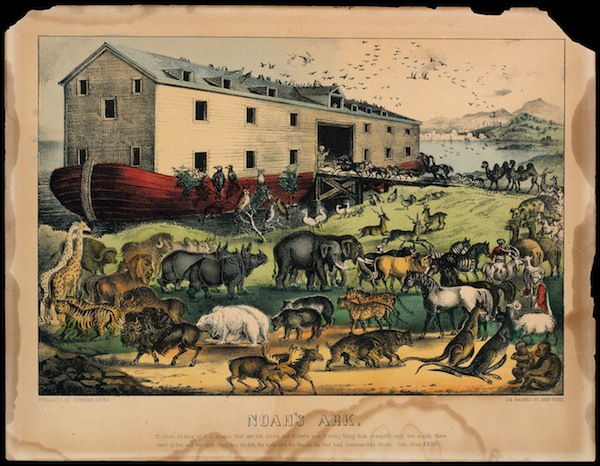

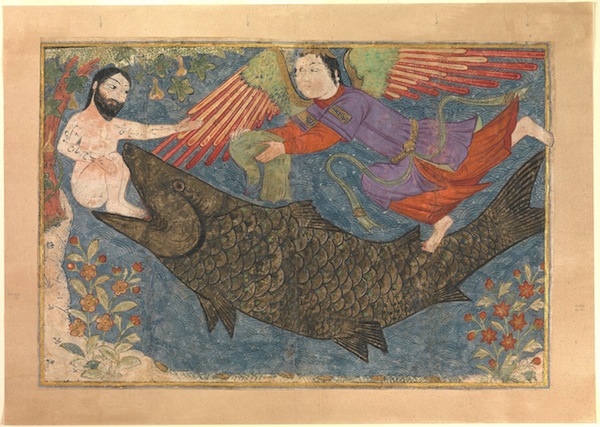

While the flood in Noah’s time, and his building of the ark, may be one of the more famous biblical weather incidents, along with the wind that battered the ship in which the prophet Jonah was hiding, they certainly are not the only ones (Metropolitan Museum of Art: Adele S. Colgate bequest, 1962)

It seems that everybody talks about the weather. Has it always been the case? While it’s admittedly impossible to prove whether it has, weather was certainly talked about in ancient times. The Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, contains many weather references.

Right off the bat, in Genesis 2:6, we find mention of mist. In this context, G-d has spent the week creating the world. On the seventh day, He fashions the first man: “but there went up a mist from the earth, and watered the whole face of the ground. Then the Lord G-d formed man of the dust of the ground….”

Five chapters later, we get to the flood story. We read about heavy, sustained rain and catastrophic flooding – “and I will cause it to rain upon the earth forty days and forty nights; and every living substance that I have made will I blot out from off the face of the earth. And the waters prevailed, and increased greatly upon the earth; and the ark went upon the face of the waters. And He blotted out every living substance which was upon the face of the ground … and Noah only was left, and they that were with him in the ark.” (Genesis 7:18,23)

Rain, however, functions as both a positive and a negative force. In Leviticus 26:4, G-d states that He will bring the rain at the proper time, enabling the trees and the land to be harvested: “I will give your rains in their season, and the land shall yield her produce, and the trees of the field shall yield their fruit.”

When the flood in Noah’s time ends, G-d promises to refrain from ever again bringing such a destructive deluge. He does this symbolically with the rainbow: “I have set My bow in the cloud, and it shall be for a token of a covenant between Me and the earth. And it shall come to pass, when I bring clouds over the earth and the bow is seen in the cloud and the waters shall no more become a flood to destroy all flesh.” (Genesis 9:13-15)

The same duality that applies to rain also applies to wind. It is a positive force, as seen in parting the Red Sea, allowing the Hebrews to safely depart from Egypt (Exodus 14:21-22). But, it is also a punishing power that drowns the Egyptian soldiers who are in pursuit.

In the Book of Jonah, G-d brings a tremendous wind with the intention of smashing apart the ship in which the reluctant prophet Jonah is hiding: “… the Lord hurled a great wind into the sea, and there was a mighty tempest in the sea, so that the ship was like to be broken.” (Jonah 1:4)

While we generally consider a whirlwind to be violent but brief, it has a different meaning in the Tanakh. In Hosea 8:7, it symbolizes ineffectiveness: “they shall reap the whirlwind; it hath no stalk, the bud that shall yield no meal.” Nonetheless, the whirlwind is also a blessing, which carries the prophet Elijah to heaven: “Elijah went up by a whirlwind into heaven. And Elisha saw him no more.” (2 Kings 2:11-12)

Other storm-related phenomena appear in the books of the Hebrew Bible. Both thunder and lightning, for example, are mentioned in the Book of Job, chapters 36 and 37: “He covereth His hands with the lightning and giveth it a charge that it strike the mark. G-d thundereth marvellously with His voice.” Likewise, the prophet Isaiah warns that G-d plans to bring thunder: “There shall be a visitation from the Lord of hosts with thunder.” (Isaiah, 29:6)

Hail is also written about in a few places. In Ezekiel 13:11 and 13, G-d threatens to bring a hailstorm. Significantly, in the Book of Exodus (9:18,25-26), hail is one of the 10 plagues G-d casts down upon the Egyptian people because of Pharaoh’s intransigence against freeing the Hebrew slaves: “Behold, tomorrow about this time I will cause it to rain a very grievous hail, such as hath not been in Egypt since the day it was founded even until now. And the hail smote throughout all the land of Egypt all that was in the field, both man and beast; and the hail smote every herb of the field and broke every tree of the field. Only in the land of Goshen, where the children of Israel were, was there no hail.”

The Tanakh likewise has references to snow in a few places, though there is practically no mention of snow having fallen – almost always, snow is used metaphorically. Thus, in Exodus 4:6, someone with leprosy has “skin white as snow.” Later, this phrase is repeated in Number 12:10 when Miriam, Moses’ sister, has leprosy.

The lack of precipitation is likewise an issue. Similar to hail, drought is used as a threat or as an actual way of punishing the Hebrews. As the

Hebrews were an agricultural society, a drought meant crop failure: “And if ye will not … hearken unto Me, then I will chastise you seven times more for your sins. I will make your heaven as iron and your earth as brass … your land shall not yield her produce, neither shall the trees of the land yield their fruit.” (Leviticus 26:18-20)

Meteorology has certainly advanced since ancient times, of course. Back then, there were no radar, satellites, radiosondes, supercomputers or advanced multidisciplinary weather graphs to interpret or predict the weather. In the Tanakh, the chief forecaster, G-d, is also the creator of these weather situations. As such, He has a considerable edge over everyone and everything.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.