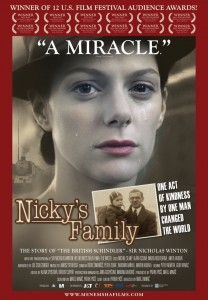

The Wallenberg-Sugihara Civil Courage Society will mark Vancouver Raoul Wallenberg Day on Jan. 19 with the screening of the documentary Nicky’s Family, about Holocaust hero Nicholas Winton.

Now 104 years old, Winton lives in England (where he was born). The story of his heroism during the Holocaust starts in 1938, when he was a stockbroker. Receiving a letter from a friend in Prague about the plight of Jews in German-occupied Czechoslovakia, he traveled there to assess the situation for himself. Shocked at what he witnessed, he established an organization to aid children from Jewish families, setting up office in his hotel room in Prague, from which he eventually expanded.

The director of Nicky’s Family, Matej Minac, said in an interview on Czech Radio in 2003: “When he came here to Prague, and wanted to rescue all these children, and he had a plan how to do it, everybody was telling him – you know, it’s absurd. You can never manage it. The British won’t let the children in. The Gestapo won’t let the children out. You don’t have the money, so how do you want to do it? It’s crazy. And Winton said that anything that is reasonable can be achieved.”

After Kristallnacht, in November 1938, the British Parliament approved the entry of refugees younger than 17 into the country, if they had a place to stay and a warranty was paid. Knowing this, Winton left his friends in Prague to manage the gathering of the children there and returned to London, where he started a campaign to find foster homes and the necessary guarantees for as many children as he could.

Winton also organized for the Jewish children to be transported on trains and then on to ferries to England, where the foster families met them. The operation later became known as the Czech Kindertransport. It lasted until the official start of the Second World War on Sept. 1, 1939, by which time 669 of “his children” had arrived in England. He kept records of the names and addresses of the children, their parents and their foster families. Most of the Jewish parents in Prague perished during the Holocaust.

Winton never told anyone of this enterprise. Fifty years after the fact, his wife found a suitcase in the attic with all his wartime documentation. She contacted the BBC, and they sent letters to the addresses of the foster families. Several dozen people responded. Most of them didn’t know the identity of their rescuer. His “children” and their children and grandchildren now number more than 6,000.

A 1988 TV program about the reunion of Winton and dozens of the children he had saved started a snowball of recognition; among the honors, Winton was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II.

In the late 1990s, Minac was searching for a theme for his next film. The Czech director read Pearls of Childhood by Vera Gissin, in which she mentions Winton and his rescue operation.

“I was astonished,” said Minac in the aforementioned radio interview. “That’s exactly what I needed for my story. I wrote a film treatment and I asked one lady, Alice Klimova, whether she could translate it into English. She said: ‘Matej, I think you have a few mistakes in your treatment, especially the scene in the train station, when the children are leaving for Britain.’ I said: ‘How do you know?’ And she said: ‘I know because I was one of those children, of Winton’s children…. I was only four-and-a-half years old. I don’t remember it so well. Why don’t you call Nicky, Nicky Winton?’ And I said: ‘How do you mean Nicky Winton? He’s still alive?’ She said: ‘Yes. He’d be very happy to talk to you, he’s a nice person, and I’m sure he would help.’ Two months later, I visited Nicky. We spent a beautiful afternoon together, and I knew that I can’t do only one film … but I will have to do also a documentary….”

In the end, Minac made three movies about Winton: one feature, All My Loved Ones (1999), the documentary The Power of Good: Nicholas Winton (2002), which won an Emmy Award, and Nicky’s Family (2011), which includes reenactments and never-before-seen archival footage, as well as interviews with Winton and a number of those he rescued.

The Wallenberg-Sugihara Civil Courage Society, which is hosting the Nicky’s Family screening and reception here, incorporated in April 2013, Deborah Ross-Grayman, one of the society’s founding members, told the Independent. “This was the natural outgrowth of the Raoul Wallenberg Day event, which began in 1986 with the placement of a plaque in Queen Elizabeth Park. It was revived on the 20th anniversary in 2006, as a cooperative event sponsored by the honorary Swedish consul, Anders Neumuller, and the Vancouver Second Generation Group…. We formed the society in order to be able to formally present an award for civil courage, and so acknowledge and support such heroic acts today.”

She added that approximately 50 diplomats from different countries risked their lives and careers to save the lives of Jews during the Second World War. “We have shown films highlighting the acts of Wallenberg, Sweden, and Chiune Sugihara, Japan, [whose visa saved Ross-Grayman’s mother’s life] as well as people from Chile, Portugal and Spain. Wallenberg saved approximately 100,000 people and Sugihara saved approximately 6,000. Their names stand as a symbol for all such courageous and heroic acts.”

Nicky’s Family will screen at the Jewish Community Centre of Greater Vancouver’s Rothstein Theatre on Jan. 19 at 1:30 p.m.

Olga Livshin is a Vancouver freelance writer. She can be reached at olgagodim@gmail.com.