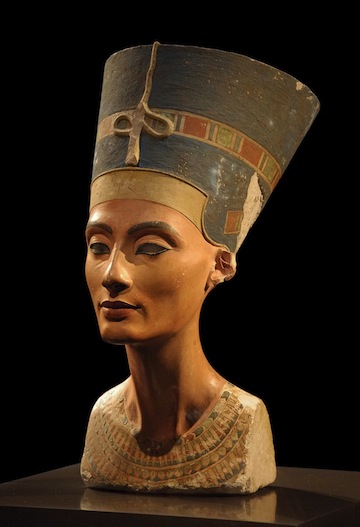

The head of Hatshepsut, in Pergamon Museum, Berlin, 2018. (photo by Richard Mortell, 2018)

As we all know from the Passover story, Pharaoh was one stubborn guy. On five occasions, Moses and Aaron tried to persuade Pharaoh to let the Hebrews go, but Pharaoh wouldn’t budge. In Exodus 7:13 and 7:22, Pharaoh hardens his heart in response to Moses’ pleading. Moreover, Pharaoh made his heart heavy in three other instances, as described in Exodus 8:11, 8:15 and 8:28. What would have happened if Moses and Aaron had come up against a female Pharaoh? Would the story have played out differently?

Let us begin by recalling that, if it hadn’t been for the curiosity and kindness of Pharaoh’s nameless daughter – though, in Judaism, she is later referred to as Thermuthis and even later as Bithiah – Moses would not have been rescued from his floating basket. The future leader of the Hebrew exodus from Egypt would not have lived, and the exodus would not have occurred as we know it.

There were at least six female rulers during the long period in which pharaohs ruled, and perhaps as many as 12. From what has been pieced together, these women sometimes had to disguise their female identity. Some adopted king titles, others exercised force to get their way.

Take Hatshepsut, for example, who was pharaoh of the New Kingdom, or Egyptian Empire, from circa 1479 BCE to 1458 BCE. She nominated herself and then filled the role of pharaoh by claiming her father (the earlier pharaoh) had wanted her to take over from him. Probably understanding that her position was tenuous – both by virtue of her sex and the unconventional way in which she had gained the throne – she reinvented herself. In visual art, she had herself portrayed as a male pharaoh, and ruled as such for more than 20 years. (See “The queen who would be king” at smithsonianmag.com.)

Initially depicted as a slim, graceful queen, within a few years, she changed her image to appear as a full-blown, flail-and-crook-wielding king, with the broad, bare chest of a man and the false beard typical of a male pharaoh. But Prof. Mary-Ann Pouls Wegner notes, however, in a 2015 article on toronto.com, that Hatshepsut’s statues have thin waists, “with nods to her female physique.”

Hatshepsut also took a new name, Maatkare, sometimes translated as truth (maat) is the soul (ka) of the sun god (Re). The key word here is maat, the ancient Egyptian expression for order and justice as established by the gods. Maintaining and perpetuating maat to ensure the prosperity and stability of the country required a legitimate pharaoh who could speak directly with the gods, which is something only pharaohs were said to have been able to do. By calling herself Maatkare, Hatshepsut was likely reassuring her people that they had a rightful ruler on the throne. She seemingly succeeded, as her 20-plus-year reign was a more or less peaceful time.

One important way pharaohs affirmed maat was by creating monuments, and Hatshepsut’s building projects were among the most ambitious of any pharaoh’s. She began with the erection of two 100-foot-tall obelisks at the great temple complex at Karnak. She likewise had important roads built. Still, her most ambitious project was her own memorial. At Deir el-Bahri, just across the Nile from Thebes, she erected an immense temple, used for special religious rites connected to the cult that would guarantee Hatsheput perpetual life after death. (See livescience.com/62614-hatshepsut.html.)

In life, Hatshepsut felt compelled to depict herself as a male ruler. In death, however, her true colours (pun intended) seem to surface. Exams conducted on her mummy reveal that, at the time of entombment, she was wearing black and red nail polish. Furthermore, according to sciencedaily.com, Michael Höveler-Müller, former curator of the Bonn University Egyptian Museum, reports that a filigree container bearing the queen’s name may have contained the remains of a special perfume, an incense mixture.

Nefertiti similarly hid her femininity, even though today she is the most visually reproduced ancient Egyptian female ruler. According to Prof. Kara Cooney, author of the book When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt, Nefertiti cleaned up the mess that the men before her had made. She wasn’t interested in her own ambition, it seems, as she hid all evidence of having taken power, ruling alongside her husband. Yet, at the Karnak temples, there is twice as much Nefertiti artwork as there is of Akhenaten, her husband, who was king from about 1353 BCE to 1336 BCE. There are even scenes of her smiting enemies and decorating the throne with images of captives.

Despite her great power – she and her husband had pushed through a monotheistic form of pagan worship – Nefertiti disappears from all depictions after 12 years of rule. The reason for her disappearance is unknown. Some scholars believe she died, while others speculate she was elevated to the status of co-regent—equal in power to the pharaoh – and began to dress herself as a man. Other theories suggest she became known as Pharaoh Smenkhkare, ruling Egypt after her husband’s death, or that she was exiled when the worship of the deity Amen-Ra came back into vogue.

The Cleopatra clan sharply contrasts with the above two peacekeeping female pharaohs. In a December 2018 National Geographic interview about her book, Cooney explains that, when it comes to incest and violence, Cleopatra family members were no slouches. Cleopatra II (who ruled in the second century BCE) married her brother, but then they had a huge falling out and the brother/husband ended up dead. So, Cleopatra II married another brother. Her daughter, Cleopatra III, then ended up overthrowing and exiling her mother. Cleopatra III took up with her uncle, Cleopatra II’s brother, who sent Cleopatra II a package containing her own son, cut up into little bits, as a birthday present. Eventually, they all got back together for political reasons. (See nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/queens-egypt-pharaohs-nefertiti-cleopatra-book-talk.)

It’s time to return to the question posed at the beginning of this article, about whether the exodus story would have turned out differently if there had been a female pharaoh in charge.

Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, on myjewishlearning.com, analyzes the actions of the pharaoh Moses and Aaron encountered. She reminds us of what Rabbi Simon ben Lakish wrote about this pharaoh. In Exodus Rabbah, ben Lakish states, “Since G-d sent [the opportunity for repentance and doing the right thing] five times to him and he sent no notice, G-d then said, ‘You have stiffened your neck and hardened your heart on your own…. So it was that the heart of Pharaoh did not receive the words of G-d.’ In other words, Pharaoh sealed his own fate, for himself and his relationship with G-d.” Only at this point does G-d intervene by hardening Pharaoh’s heart, so that the plagues can end and the Hebrews can leave Egypt.

According to When Women Ruled the World author Cooney, the emotionality of female pharaohs is key. In that 2018 National Geographic interview, she says, “that ability to cry or feel someone else’s pain…. It is that emotionality that causes women to commit less violent acts, not want to wage war and be more nuanced in their decision-making. It is what pulls the hand away from the red button rather than slamming the fist down upon it. These women ruled in a way that kept the men around them safe and ensured their dynasties continued.”

There is the possibility then that, had Moses and Aaron encountered a female pharaoh, she might have concluded that all the pain and suffering from the plagues wasn’t worth it – neither for herself, personally, nor her Egyptian subjects. Perhaps without a big fuss, or at least with less of one, she would have let Moses lead the Jews out of Egypt.

Deborah Rubin Fields is an Israel-based features writer. She is also the author of Take a Peek Inside: A Child’s Guide to Radiology Exams, published in English, Hebrew and Arabic.