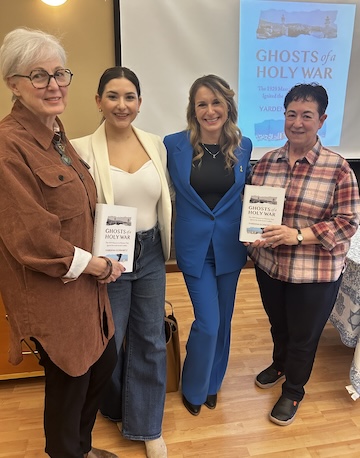

The White Rock/South Surrey Jewish Community Centre hosted Yardena Schwartz, author of Ghosts of a Holy War: The 1929 Massacre in Palestine that Ignited the Arab-Israeli Conflict, on Feb. 23.

At the event, held in partnership with the Jewish Federation of Greater Vancouver and the Cherie Smith JCC Jewish Book Festival, Schwartz – an award-winning producer and journalist – spoke about her book and then answered some questions from the audience.

Schwartz has worked for NBC, among other organizations, and reported for many publications, including the Wall Street Journal, New York Times and Foreign Policy. She lived in Israel from 2013 to 2023.

While working as a freelance journalist in Tel Aviv, Schwartz was introduced to a family from Memphis, Tenn., who had a box of letters written by their late uncle, David Shainberg, who was one of the 70 Jews killed by some of the Arab residents of Hebron during the massacre in 1929. He had sailed to Palestine in 1928, and studied at Hebron Yeshivah; he wrote hundreds of letters to his family about how Jews and Arabs were living together, coexisting, peacefully. Schwartz spoke about those letters, and the massacre and how it relates to Oct. 7.

Helen Mann, who works with the Jewish Federation and is also a part of the White Rock/South Surrey Jewish community, told the Independent that reading Schwartz’s book amid growing antisemitism was empowering, that “it felt more important than ever to spread the historical truth of our people and this contentious and tiny piece of land, especially in such a tiny Jewish community we are in, of White Rock/South Surrey.”

Mann said there is so much misinformation being disseminated, on social media in particular.

“Yardena has meticulously delved through and cited sources to do the work for us, and weave that history into a page-turner,” she said. “While I hope this book gets into the hands of anyone who wishes to speak on the current conflict and politics, it’s of high priority that we as a Jewish community are educated on our own history; to know who we are in order to know where we are going.”

The Jewish Independent spoke with Schwartz after the event.

JI: What types of research did you do for the book?

YS: My research started with interviews in Hebron with Palestinians and Israelis living there. And then, from there, I focused on the period of history that preceded the massacre, so 1928 and 1929. That involved looking at archival newspaper articles in places like the Palestine Post and the New York Times, and Arabic press… There’s an archive in Hebron that I spent a lot of time in, archives in Jerusalem, and Hagana Archives in Tel Aviv. This was during COVID, so I couldn’t go to the London archives, but some other authors who had been there and got materials were kind enough to share them with me.

It was a lot of archival research, a lot of interviews: hundreds of hours of interviews with Israelis and Palestinians in Hebron between 2019 and 2023.

I also read as many books as I could that were focused on that period. There were two books that were really helpful in my research. One was Hillel Cohen’s Year Zero of the Arab Israeli Conflict, which tells the story not just of the Hebron massacre, but of the riots of 1929. And it’s very succinct, it just focuses on the riots, like none of the history before or after. Then, a book by Orin Kessler, Palestine 1936, which focused on the Great Arab Revolt from 1936 to 1939.

JI: During your research, did you find any information that surprised you in a way?

YS: Well, the letters that David Shainberg wrote to his family were really eye-opening for me in painting a picture of what Hebron was like before the massacre and what Hebron was like during the British Mandate before the massacre…. I had never known that Jews and Muslims had lived side by side in peace in Hebron and owned businesses and drank coffee together. That was really surprising to me, given what Hebron is today.

But I think what shocked me most during my research was what I discovered about the mufti, the grand mufti, Amin al-Husseini, who was the first leader of the Palestinian people, and, specifically, his role during the Holocaust, his affiliation with the Nazis, his role as a Nazi, and his role in recruiting tens of thousands of Muslims to fight for the Nazis – and the fact that he lived the rest of his life out in the open. I mean, he was wanted for Nazi war crimes and yet he didn’t have to live out the rest of his life in hiding, like so many Nazis did…. He was never arrested, never was prosecuted or put on trial for his crimes.

JI: Since this is your first book, how was the overall experience, and what challenged you the most?

YS: I think what challenged me the most was giving birth to two children during the course of writing this book. I honestly still have no idea how I wrote a book while raising two kids – my kids are now 2 and 4-and-a-half. I was pregnant with my first child when I started this research … and it was really difficult to write about such a depressing, heavy subject while bringing new life into this world. It was really difficult.

It had always been a dream of mine to write a book. I’d been a journalist for years, but I don’t think I could grasp, until writing this book, just how difficult writing a book is, especially something that covers 100 years of history. So, it was … a tremendous undertaking. Sometimes, it was torturous, but other times it was really fulfilling and especially now that it’s out there in the world, and hearing from readers is just like an incomparable experience…. I feel really blessed that I was entrusted with these letters by these families. Without them, this book wouldn’t have come to fruition, basically.

JI: What key message do you want readers to take from the book?

YS: I think my key message is that we will never be able to resolve this conflict if we can’t agree on the facts that drive it and the history that precedes this tragic moment we’re in. And, I think, to anyone who wants to see peace in Israel, peace between Israel and Palestinians, I hope they’ll read this book. I hope they’ll learn the lessons of history, so that we can stop repeating the mistakes of the past.

Chloe Heuchert is an historian specializing in Canadian Jewish history. During her master’s program at Trinity Western University, she focused on Jewish internment in Quebec during the Second World War.