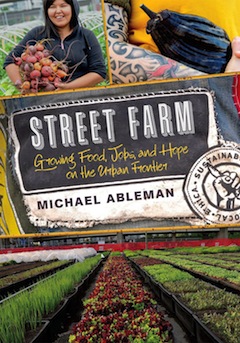

In the book Street Farm: Growing Food, Jobs and Hope on the Urban Frontier, Michael Ableman shares the story of how Downtown Eastside residents helped create Sole Food Street Farms. (photo by Michael Ableman; Street Farm [Chelsea Green, 2016])

In his book Street Farm: Growing Food, Jobs and Hope on the Urban Frontier (Chelsea Green, 2016), Michael Ableman shares the inspirational story of how residents in one of the poorest urban areas in North America – Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside – helped create Sole Food Street Farms.

Ableman has been a leading voice in the organic sector for 45 years and is the owner of Foxglove Farm (an organic 120-acre plot of land on Salt Spring Island), an author and a public speaker.

“I became incredibly impassioned by the power of food and farming to heal the world, to change people’s lives, to reconnect them,” Ableman told the Independent. “I came to see farming, not as the industrial activity that it had become since World War Two, but as a community venture to be shared by everyone participating.

“I think that has formed all my endeavours, all the projects I’ve done, all the work I’ve done – not all successfully … but it’s a function of being 63 years old … that you begin to recognize the importance of talking about those areas where you fall short … because, it’s a lot more informative than patting yourself on the back.”

Ableman responded to a call for strategies to help transform the Downtown Eastside, which is the lowest-income community in Canada, “with the highest rates of intravenous drug use perhaps in North America … mental illness, open prostitution,” he said.

“I agreed to come to a meeting with a number of social service agencies on the Downtown Eastside who wanted to come up with some creative ideas. They had access to a half-acre parking lot next to one of the dive hotels. And, you know, one meeting led to the next and, before you know it, I was directing and envisioning the birth of this amazing social enterprise that we started … which became Sole Food Street Farms.”

Now, after seven years in operation, the farm’s four-plus acres on pavement is producing 25 tons of food annually, employing up to 30 people, and is having a profound impact on people’s lives, as well as on how urban agriculture is perceived.

In his book, Ableman tells the story of the people he is working with, how their lives are being affected, and how they work with municipal governments to do what had never been done before on this scale.

“It is my belief that the smaller production units, whether front or back yards, are actually incredibly important for our future,” said Ableman. “And, probably, in the end, my goal has always been to see individuals and families put farmers out of business, by growing for themselves. But, we have a long way to go. My goal is still very much focused on jobs and producing quantities of food.”

Every city has two main challenges if you’re going to attempt to do gardening or agriculture, he said. “Number one, the soils are either too contaminated to grow in or are paved over. And, number two, the value of the land is too high for landowners or municipalities to give up.

“We felt it was incredibly important in the enterprise we created in Vancouver to address those issues. So, we designed a very innovative box system and we had these boxes manufactured. The boxes are isolated from contamination or pavement. They have interconnected drains. They are stackable, nestable, have pockets for hoops, and are indestructible.”

Ableman said Street Farm is a “why-to” book, though they are “producing an actual tool kit, a companion to this book, the nuts and bolts of how we did it.” But, Street Farm, he said, “is a book that says, ‘Look, even under the worst circumstances, the poorest neighbourhoods, here is what individuals in a community can do to improve their lives and here’s how they did it.’ So, if we could do it here, you can do it elsewhere. We’re there to inspire people and make them understand that you have to do it in a way that addresses the particular needs of your community – the culture, economics, ethnicity. All those things have to be considered when setting something like this up – knowing who you are serving and why.”

Ableman said Street Farm is a “why-to” book, though they are “producing an actual tool kit, a companion to this book, the nuts and bolts of how we did it.” But, Street Farm, he said, “is a book that says, ‘Look, even under the worst circumstances, the poorest neighbourhoods, here is what individuals in a community can do to improve their lives and here’s how they did it.’ So, if we could do it here, you can do it elsewhere. We’re there to inspire people and make them understand that you have to do it in a way that addresses the particular needs of your community – the culture, economics, ethnicity. All those things have to be considered when setting something like this up – knowing who you are serving and why.”

Since the book came out, the project itself has evolved. In fact, Sole Food had to move their largest farm location a few months ago, which was a huge undertaking.

“When you write a book, the story is the story that existed at the time the manuscript was submitted and accepted by the publisher,” said Ableman. “But, nothing stays the same, especially in the work we do. Certainly, the individuals I write about, their lives have changed. We’ve learned more things … and we shift our systems accordingly. It’s really the wonder and beauty of agriculture, that it requires that each of us approach it with what I call a ‘beginner’s mind’ – never having a preconception, always being open to the moment. It’s a biological system, and requires a day-to-day, moment-to-moment response to that system. That’s the beauty, what we love about it – it always changes.”

He recalled, “For my bar mitzvah, the section of the Torah I read from was about the land of milk and honey. It was essentially about creating a fertile environment, abundance and nutrition from the land. At 13, the last thing I ever thought I’d be involved with was agriculture.

“If you really go back to the roots of our tradition – Judaism – we have strong roots in the land, strong agrarian roots. That doesn’t mean each of us has to be a farmer. What it means though is that we have a responsibility to create relationships and connections with those who are, and trying to do it well.”

It’s so much more than agriculture.

“While we generate $300,000 every year in products grown and sold,” said Ableman, “we still have to raise another $300,000 to support the social component of what we do – the trainings, taking people to the hospital, rain gear, literacy programs, meals. We are recognized as a world-class model. Participate in whatever way you can in your own tradition by supporting local enterprises trying to do the right thing.”

More about Ableman and Sole Food Farms can be found at solefoodfarms.com.

Rebeca Kuropatwa is a Winnipeg freelance writer.