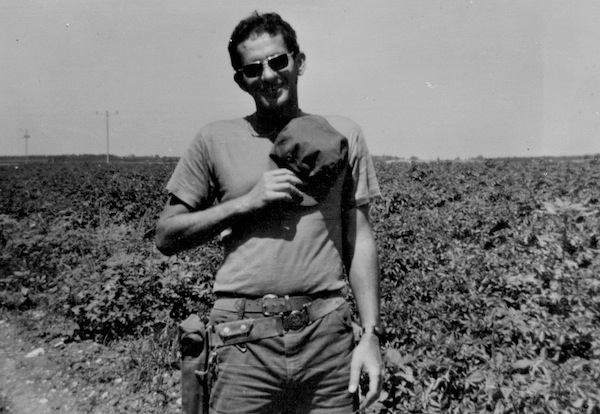

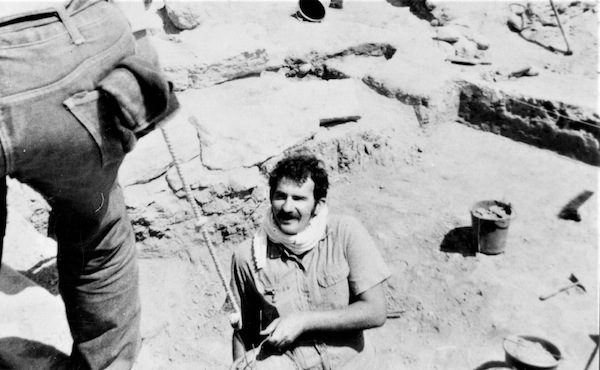

Patroling the kibbutz perimeter. (photo from Victor Neuman)

In this eight-part series, the author recounts his life in Israel around the time of the 1973 Yom Kippur War. The events and people described are real but, for reasons of privacy, the names are fictitious.

Part 5: Night Guard Duty on the Kibbutz

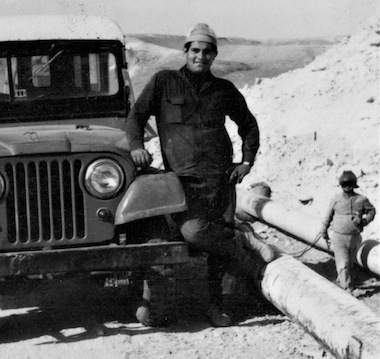

Lev, the banana boss, was in his early 30s and a miracle worker. He was back on the kibbutz and strolling toward me. He had talked the army into releasing him so he could save his banana fields. I was not surprised he had pulled it off. Lev was originally from the United States and a dedicated Zionist. He had long ago concluded that the only proper place for a Jew was in Israel and so he immigrated. Always determined in what he wanted, he bulldozed his way through kibbutz apprehensions to single-handedly create the banana crop as a major branch of our agricultural sector. And he was fearless to a fault.

“Fearless to a fault” may sound like a contradiction. It’s not. The right amount of fearlessness is courage. The wrong amount is stupidity. In my opinion, Lev was sometimes at the wrong end of that equation. Here’s an example.

Before the war, Lev was fed up with the theft from our banana fields and had no confidence that the village police from the nearby Arab town would take any action. The culprits were likely from the town and might even have been relatives of the cops. I had to agree with Lev – the only time I had seen any action from these police was when they drove up to the kibbutz to extort chickens for their next village wedding.

One day, Lev had six of us arm ourselves with clubs and do a stakeout in the banana fields. We had a German Shepherd named Ledie to help take down anyone we caught. Before long, two Arab teenagers appeared, checking for ripe bananas. They came toward where I was hiding. I jumped up but I had moved too early and they raced for their village. Only Lev, the dog and I were near enough to give chase. It was a farce. The teens were lean and fast. Lev smoked two packs a day. Our dog was never trained to be aggressive and was an older dog as well. So, it was the two teenagers way in front, me next, Lev a distant fourth and the dog in last place – tail wagging madly the whole time. I gave up and stopped, but Lev ran past me and yelled, “Come on!”

By the time we arrived at the village, the two thieves had vanished and our dog also had disappeared, likely returning to the kibbutz. I wanted to go back, too, but Lev wasn’t done and I couldn’t leave him on his own. Like a gunslinger minus the gun, he walked us right into the first building we came to. It was some kind of coffee house, full of locals sitting at tables sipping their drinks. All conversation and sipping ceased when we barged in. They all stared at us. I felt like I was in a bad Spaghetti Western. I was convinced Lev was going to get us killed.

Lev stomped around, demanding to know if anybody had seen the two boys. Heads were shaking. Not satisfied, he gave a description of what they looked like and the clothes they were wearing. Heads kept shaking. He then demanded that everybody keep an eye out for these banana thieves and report them to our kibbutz. To my astonishment, heads nodded. I think we had caught them by surprise and then Lev’s pure chutzpah had won the day. Walking out in one piece was a win for me, while Lev was angry at not catching anybody; surviving was not one of his concerns.

Now you know what I mean by “fearless to a fault.” And now, here was fearless-to-a-fault Lev walking up to me.

“Shalom, Victor. I’m back so I’ll be taking over the irrigation. I wanted to keep you on it, but Gidon says he needs you for guard duty. You better see him. And thanks for looking after the bananas. I expected half of them to be dead but they are all good. Nice job.”

High praise from Lev, who rarely expressed gratitude to anybody. The bananas were like children to him and I was the babysitter who, surprisingly, hadn’t murdered any.

Gidon told me I was to patrol the kibbutz from dusk to dawn for the next week at least. He gave me an ammunition belt, a flashlight and a first-aid kit with pressure bandages to patch up anybody I shot inappropriately. He also gave me Chauncy, the English guy. Chauncy was one of those hapless tourist volunteers who came to experience kibbutz life and was experiencing more than he bargained for. Though he wasn’t Jewish, he gamely agreed to be my assistant on patrol.

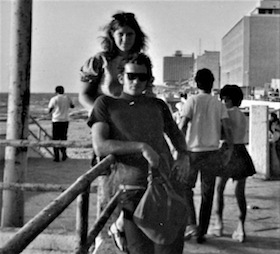

Our first patrol had a slow start. Chauncy begged me to let him hold the Uzi long enough to get his picture taken. I didn’t want to, but figured it would be better to get it out of his system. I removed the ammunition clip and handed him the Uzi. He gave me his camera and I took a half-dozen pictures of him, empty gun at the ready, looking steely-eyed and staring into the dark. I was thinking he was an idiot but then remembered the photos I had made Tamar take when I first got my weapon. She thought I was an idiot. Israelis would never think of getting this kind of snapshot, as Canadians wouldn’t think of getting their picture taken in their kitchen holding a spatula. Why record it? In this country, everybody has a spatula.

We walked the perimeter for about a week. Early evening was the best, as kibbutz members stopped to chat and the time went quickly. Adding to our duties was the requirement that we join others in checking cars that were coming up the driveway and searching them for bombs. I was particularly happy to intercept the village police who had come on another of their chicken runs. We made them get out of their car and stand around while we did a thorough, very slow check of their vehicle. The chicken-stealing cops were not nearly as annoyed as I had hoped. I was thinking we’d need to do a strip search next time.

As the night wore on, everybody went to sleep and it was just Chauncy and I walking the perimeter. As per Gidon’s instructions, we didn’t go to the dining hall to scrounge for food and thus take ourselves away from our rounds. We carried our lunches and ate under the security lights. I was always conscious of how dark it was beyond the reach of those lights and how impossible it would be to see anyone coming. On the other hand, Chauncy and I, walking directly under the lights, were highly visible from far away.

It became a nagging question in my mind as to how effective night guard duty was when Chauncy and I were always in plain view while the bad guys were always hidden. I confronted Gidon about it one day and his reply was, “When you are shot, it will alert the rest of the kibbutz.” I wished he had had a grin on his face, but he didn’t. I was just thankful he hadn’t ended with “Are we understanding?” We were not.

I never told Chauncy about that conversation but I think he detected my increased wariness. A certain morbidity came over me. In trying to come to terms with the possibility of death, I tried to control the fear by embracing the notion. I decided one night we would have our meal in the kibbutz cemetery. Chauncy was freaked but I put it to him that the dead were dead and gone. Also, I argued, the headstones made good back rests for eating in comfort. To pass the time, I read the Hebrew on some of the stones; the easiest part to grasp being the date of death and age of the departed. Many were in their 20s and had died in 1948, likely in the War of Independence. They were close to my age and Chauncy’s. It made me think of how endless the fighting was in this land. The dead of one war pondered by participants in another, with two other conflicts in between. We only had lunch in the cemetery that one time.

I never had to shoot anybody during my stint as night guard but I did come close once. Chauncy and I were in the area of the mechanical shop at around two in the morning when we heard noises coming from the shop and saw the lights were on. The kibbutz was generally very quiet at night. There was no shift work besides guard duty so everyone should have been in bed.

I told Chauncy to stay behind me as we entered the shop to investigate. For the first time in all my guard duty, I slid the thumb switch of my Uzi from safety to automatic.

Chauncy whispered, “Jesus!”

We got as close to the noise as we could and then I stepped around a corner with my Uzi leveled.

It was a kibbutz teenager named Uri. Apparently, Uri had a bout of insomnia and decided he might as well go to the shop and keep working on his project. He was trying to make a go-kart out of discarded tractor parts. Uri had almost gotten a permanent cure for his sleeplessness. I had almost shot a 15-year-old kid.

(Next Time: The War Comes Home)

(Previously: “Learning the lay of the land”; “When Afula road went quiet”; “Tending the banana fields in war”; “Weapon training begins”)

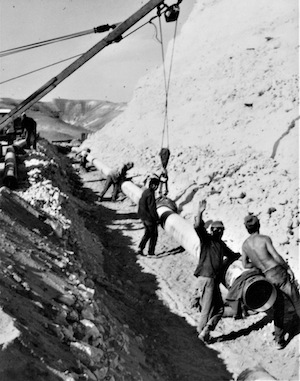

Victor Neuman was born in the former Soviet Union, where his family sought refuge after fleeing Poland during the Second World War. The family immigrated to Canada in 1948 and Neuman grew up in the Greater Vancouver area. He attended the University of British Columbia and obtained a BA and MA with majors in English literature and creative writing. Between 1968 and 1974, he made two trips to Israel, one of which landed him on a kibbutz at the time of the 1973 Yom Kippur war. Upon his return to Canada, he studied Survey Technology at BCIT and went on to a career of designing highways for the Province of British Columbia and the firm of Binnie Civil Engineering Consultants. When he retired, he reconnected with his roots in creative writing and began writing scripts for Vancouver Jewish Folk Choir concerts and articles for the Jewish Independent. Neuman and his wife, Tammy, live in southeast Vancouver and enjoy the company of friends, their extensive extended family and their four sons.