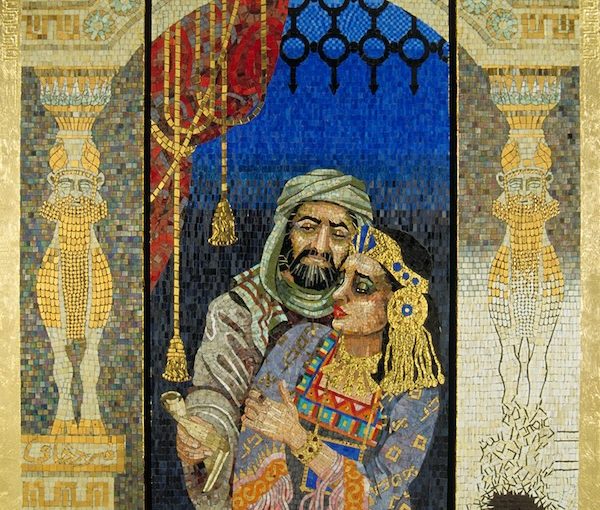

Megillat Esther, the Book of Esther, receives rave reviews. (photo from Chefallen via Wikimedia Commons)

Recently discovered among ancient Persian manuscripts and just smuggled out of Tehran in time for Purim, an anonymous writer analyzes the story of the Book of Esther.

Our community of Jews here in Shushan, Persia, has just happily read the newly written account of events of last year, 350 BCE, in our capital city and other towns in Ahasuerus’ kingdom; how evil Haman rose up against us and, with Mordecai and Queen Esther’s help, we defeated him and all our enemies and now make merry on the great day we call Purim.

This wonderful scroll, megillah in Hebrew, the Book of Esther, has circulated widely and I now offer you my view of this wonderful narrative.

The Book of Esther is an outstanding example of storytelling that will be found in every Jewish household. This tale contains all the timeless literary devices, which we Persian Jews adore: a great story, conflict and suspense, believable characters, foreshadowing and a harmonious structure.

At the opening royal feast, we meet Ahasuerus, the mighty king of Persia and see how hastily he disposes of his wife, Queen Vashti, when she disobeys him, foreshadowing the haste with which he later orders the Jews condemned to death.

Our king doesn’t enjoy being lonely, so he must find a new queen. (At this point I must modestly say that I gave him the suggestion for a beauty contest.) Once it is announced, our lovely Esther – advised by her cousin, Mordecai, not to reveal her Jewishness – wins and marries the monarch. Soon, Mordecai (end of Chapter Two), a minor court official, unearths an assassination plot against the king. Instead of informing Ahasuerus directly, Mordecai lets Esther bring the news. Thus both can win favor with the ruler. Mordecai’s discovery, inscribed in the king’s Book of Chronicles, is pertinent to the story’s development.

The main protagonists – the foolish king, the lovely Esther, the wise Mordecai – have made their appearance. Now, for conflict and tension enter the villain, Haman, in Chapter Three. Everyone must bow to him, but Mordecai refuses. When Haman realizes that Mordecai won’t bow to him because it is against Mordecai’s Jewish faith, he plans to destroy all the Jews as punishment. Lots – purim in Hebrew – are cast to decide the day to carry out his murderous scheme, and the pre-spring month of Adar is chosen for the draw.

To vent his hatred against one recalcitrant Jew, why should Haman want to kill all Jews? But since one woman’s action (Vashti) prompted a law for all women, a precedent has been set for mass retaliation for an individual’s misdemeanor.

Since the insubordinate Mordecai is Jewish, Haman infers that all Jews are disobedient, that their “laws are diverse.” (3:8) Haman persuades Ahasuerus by promising as a result much silver to the royal treasury – booty from the slain Jews.

The chapter concludes. “The king and Haman sat down to drink, but the city of Shushan was perplexed….” (3:15) This passage contains a hint that people in our great city realize that a wrong had been committed against the Jews.

In contrast to the opening revelry, Chapter Four begins with mourning and pathos. Mordecai tells Esther of the coming disaster and asks her to intercede. Fearing for her own life, she hesitates, for she knows no one may come before the king uninvited, on pain of death. Mordecai counters: your fate and that of the Jews are one, he tells her. Perhaps it is for this very reason that she has been made queen.

Esther asks the Jews in Shushan to fast three days; then she will go to the king. Here, at mid-point of the story (5:2), the reversal starts; the heroes rise, and the villain Haman’s fall, commences.

That evening, Esther prepares a banquet for the king, Haman and herself, and postpones her appeal until the following day, when all three will dine again. This artful delay adds suspense and permits the inclusion of yet another strand to the story.

Good narrative demands that some strands that later intersect should at first be left dangling. Three appear at the beginning of Chapter Six. Can Esther save the Jews at the banquet? Will Haman hang Mordecai? Has Mordecai’s loyal service to the king been forgotten?

The writer picks up strand number three. After Esther’s dinner, the insomniac king calls for the Book of Chronicles and realizes that Mordecai hasn’t been rewarded for saving his life once upon a time. The king asks who is in the court. Haman is just about to request that Mordecai be hanged for treason. The king, however, asks Haman how to bestow honors upon a deserving man. The vain Haman, assuming he’s being considered for a reward, suggests that man should ride through Shushan royally clad on horseback while all praise him. Then do so to Mordecai, the king tells Haman. The evil Haman, high-spirited the previous day, hastens home in mourning.

At the second banquet, Esther petitions for her people. The king asks her who is the perpetrator of the planned genocide? Esther points to Haman. Ahasuerus, enraged, leaves. Haman falls on Esther’s couch to beg for mercy. When the king returns, he assumes Haman is attacking the queen. Ahasuerus orders Haman hanged on the gallows that Haman had built for Mordecai.

At the close of the narrative, the villain has been destroyed, but the evil he has set into motion must be stopped – the planned execution of the Jews will go on as Persian law states that a royal edict cannot be recalled. The most the king can do is give the Jews the right of self-defence. Again, the couriers hasten to deliver the news.

In Chapter Nine the story ends. The Jews defend themselves and are victorious. To the end of the tale, an epilogue is appended. Purim is established as a holiday for all time, a day “of fasting and joy, and of sending portions to another and gifts to the poor.” (9:22)

In our story, all the characters act of their own volition. Inner human drives move them. Unlike other biblical stories, there is no deus ex machina. Not only is God not mentioned in the Book of Esther – the only book in the Bible without the word “God” – there is no hint of any supernatural force.

The book opens with feasting and joy in Shushan and in the palace; it concludes with feasting and joy for the Jews of the realm. Upon this artistically harmonious note concludes the Book of Esther, one of the most perfect narratives in the Bible.

As a child, Curt Leviant spoke ancient Persian fluently. Today he can barely say hello. His most recent book is the short story collection, Zix Zexy Ztories.