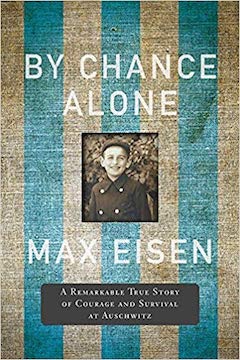

As public opinion surveys continue to tell us that vast numbers of people know little or nothing about the Holocaust, it was encouraging that Max Eisen’s memoir, By Chance Alone, became CBC Radio’s Canada Reads 2019 choice, bringing this wrenching narrative to many more eyes and ears.

Born in Czechoslovakia in 1929, Eisen enjoyed a childhood filled with shenanigans and idyllic summer excursions to his maternal family’s farm – until the Nazi invasion of his country, in 1938.

“At 9, I didn’t fully understand what was taking place, but I noticed the rising tensions in my hometown,” he writes.

“At 9, I didn’t fully understand what was taking place, but I noticed the rising tensions in my hometown,” he writes.

Eisen’s father’s friends assembled at their home to listen to a major address by the Führer on a crystal radio. “All of us understood basic German,” he writes. Hitler’s words, “Wir werden die Juden ausradieren” – “We are going to eradicate all the Jews of Europe” – clarified for the young Eisen the import of the moment.

While traumas befell the family from then on, it was in the night after the first seder in 1944 that the worst of the family’s catastrophe began to unfold.

At 2 a.m., after the family had settled into bed after what Eisen calls their “last supper,” a neighbour arrived at their property urgently insisting that the family hide in the forest because he had overheard gendarmes saying that they would gather all the Jews in the vicinity the next day. Because it was Passover and the Sabbath, Eisen’s grandfather declared that the family would not travel. At 6 a.m., gendarmes forced their way into the home, gave the family five minutes to pack a bundle and be ready to depart their home.

The complicity of bystanders before, during and after the Holocaust permeates the book.

“On both sides of the road, the townspeople jeered and cursed at us as we passed. Many were looking out the windows of the Jewish homes they now occupied.… Many townsfolk who bought goods on credit from Jews like my grandfather were happy they wouldn’t have to pay the money back. Our deportation was an economic windfall for them.”

In the chaos of arrival at Auschwitz, Eisen had no idea of the seriousness of the separation of himself, his father and uncle from the rest of their family. The three would be the only ones to survive the first selection.

The everyday “indignities and deprivations” they had experienced before quickly turned to horrors. The forced labour he endured, long shifts of excruciatingly exhausting work on starvation rations, was fatal to those less strong.

His father and uncle were moved to another barracks and, after selection one day, Eisen could not find them.

“I ran to a fenced off holding area where the SS kept the selected prisoners until they were ready to transport them to Birkenau to be gassed.… My father reached out across the wire and blessed me with a classic Jewish prayer…. The same prayer my father once uttered to bless his children every Friday evening before the Sabbath meal. Then he said, ‘If you survive, you must tell the world what happened here. Now go.’”

At one point, when Eisen let down his guard and relaxed for a moment, an SS guard delivered a blow with the butt of his gun on the back of Eisen’s head. The nearly fatal attack put Eisen in the camp’s infirmary, which proved one of the chances that led to the book’s title. A surgeon, a Polish political prisoner, assigned Eisen the job of cleaning and running the operating theatre. Although the responsibilities he was forced to undertake and the things he witnessed were appalling, the comparative comfort of the job may have saved his life.

As the Nazi regime was on its last legs, “the SS ceased distributing rations and the water system was shut down,” Eisen writes. “I woke up to the smell of cooking meat.… Several inmates sat around a small stove and watched as a pot boiled. I could not imagine how they had acquired meat, but when I crawled to the latrine where the cadavers were stacked, I noticed that some of the bodies were missing pieces from their buttocks.”

On May 6, 1945, the camp was liberated, but the term lacks much meaning in the context. Everything and everyone Eisen knew was destroyed. When the Americans provided food, a stampede of starving people led to deaths by trampling. Those who got food suffered ruptured stomachs and many died on the spot.

After overcoming a nearly fatal bout of pleurisy, Eisen faced yet more incarceration. After the communist takeover of Czechoslovakia, his plan to find freedom abroad was dashed. Because he came from the eastern, Hungarian-speaking part of the country, he tried to obtain phony Hungarian ID and join a mass of Hungarian refugees passing through to the West. Discovered, he was imprisoned for a year.

When finally released, Eisen was given 24 hours to get out of his native country. Eventually, he made his way to Canada where, since the 1980s, he has educated school kids and others about the Holocaust.

“It is in this way,” he writes, “that I have fulfilled my final promise to my father: telling the story of our collective suffering so it will never be forgotten.”