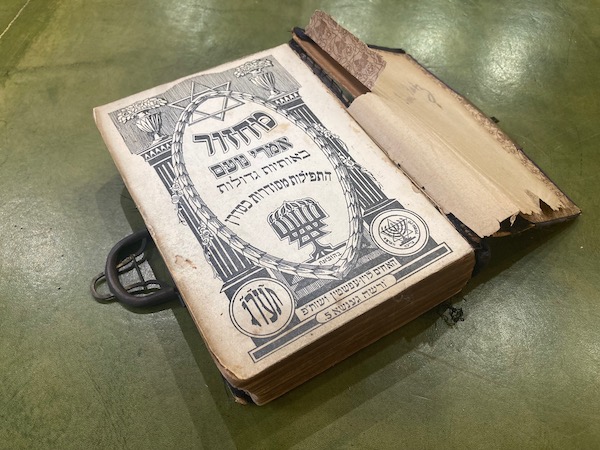

The author’s family Machzor, which was printed in Warsaw in 1913, was most likely owned by her grandfather. (photo by Shula Klinger)

Growing up, I was never taken to shul. I never saw my parents pray, read religious texts or attend any Jewish community events. I saw my maternal grandfather’s tallit case once or twice; I don’t know if he attended shul regularly. These ritual items were simply family artifacts, not elements of our daily lives.

At school, I went to Shabbat with a school friend and muddled through, not knowing the customs. I went to Jewish assembly twice a week and learned the Shema – sort of – from the other girls. With an Israeli father who spoke fluent Hebrew, I didn’t know where I fitted in. Religious Jews weren’t “our people.” My father’s religion was Zionism, not Judaism. I was English, but, at the same time, I wasn’t.

My mother passed away in 2020. As I went through her belongings, I was startled to find a Machzor (prayer book for the High Holidays) that had belonged to – I presume – her father, Dr. Bernard (Boris) Stein. It was coming apart and not just from age; it had clearly been well-used.

This was a deeply moving discovery for me. It told me that my family had once kept the High Holidays, that my ancestors did attend services and were indeed part of a spiritual community.

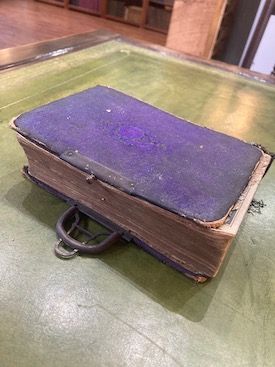

The prayer book’s worn, shabby velvet has been repaired more than once. Once bound in a rich purple velvet, glue marks are all that is left of the cover ornament. The buckle is mostly intact but the spine is roughly stitched together with cotton thread. This is not the work of a professional artisan; maybe it’s the handiwork of my grandfather himself. He was used to handling a needle and thread, though as a surgeon.

From the Cyrillic text in the front, I learned that the book was published by Levin-Epstein in Warsaw. Why would my grandfather, who was born in Lithuania and raised in South Africa, have owned a Polish Machzor?

According to Nathan Cohen in Warsaw: The Jewish Metropolis, Warsaw did not rise to prominence in Eastern European Jewish life until the second half of the 19th century. This was a result of the czar’s 1836 decree that closed down Jewish printing houses in the Russian empire. Only select printers in Vilna and Zhitomir were allowed to print in Hebrew characters. Warsaw, however, was outside the boundaries of this region, so the Jewish printing industry moved there instead. My family prayer book was published in 1913.

And what of our Machzor’s future? I don’t want to pack it up and hide it away. I want it to be a family heirloom for generations to come, and for my children to see it as they grow up. They are proud of their heritage and will also want to see that the book is well cared for.

I sought the advice of a professional. Having worked with local bookbinder Richard Smart on a Jewish Independent story about Anne Frank in late 2017, I returned with the book and a new set of questions.

Could the book be repaired? Smart said no, because “any new suede isn’t going to blend in nicely with the old … it’s very fragile.” However, he came up with another option for conserving it: building a custom box. This way, he said, “it’ll stay in one piece, but it also keeps its history of having been handled and used.” I like this approach because it prevents the book from coming to further harm, but it also preserves it as evidence of my ancestors’ religious lives.

While the book will not be in circulation, I am heartened by the knowledge that it will, at least, be safe. Even if it doesn’t form a part of my own religious practice, it won’t be discarded or tucked away like a souvenir. This Machzor will be treated in a manner that befits an ancient treasure: laid carefully in a box that is made by hand. I’m proud to be its guardian until it passes to the next generation of our family.

To see a video of Smart reaching his decision about the Machzor, visit @oldenglishbindery on Instagram.

Shula Klinger is an author and journalist living in North Vancouver.