A trove of letters between Jewish children and their parents separated by the Second World War and the Holocaust gives insight into the way families communicate in times of crisis.

Debórah Dwork, Rose Professor of Holocaust History and director of the Strassler Centre for Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Clark University in Massachusetts, has been studying the letters. On Nov. 1, she delivered the Kristallnacht Commemorative Lecture, an annual event presented by the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre in partnership with Congregation Beth Israel.

During the Second World War, postal service between belligerent or occupied countries ceased, but an individual in neutral Switzerland could convey messages between people in countries on either side of the conflict. Largely by happenstance, Elisabeth Luz, a Swiss woman living outside Zurich, helped many Jewish families maintain contact. After Luz, an unmarried woman who became known to many as “Tante Elisabeth,” had forwarded messages for a few families, word of mouth led to unsolicited requests from children who had been sent to presumed safety in France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Britain.

“News about the aunt who forwarded letters spread quickly and Tante Elisabeth gained many nieces and nephews,” said Dwork. “She soon became their counselor and confidant, although nearly none ever met her.”

“Please pardon us that we write you without having permission to do so,” wrote Robert Hess and his brother. “Adolf is 12 years old and I am 14 years. We live in an OSE [Jewish philanthropic organization] home and have been selected for immigration to America. We write to you because we would like to write to our mother and have no other possibility. Please write our mother that she can write us via you. We must ask our mother permission to travel to America.… Can you also send us a photo of her?” The boys provided their address, their mother’s address in Vienna and a photograph of themselves.

“She did not disappoint,” Dwork said of Luz, “and they were included in that transport to America.”

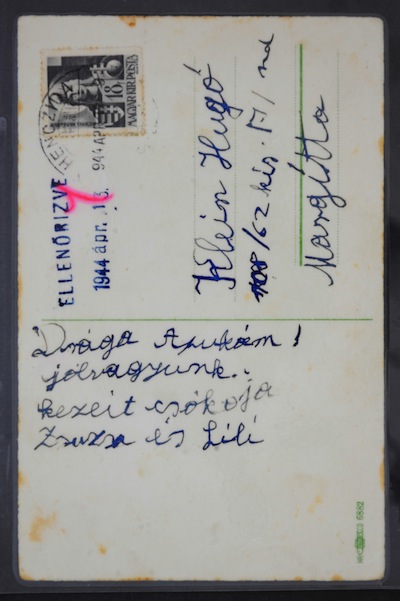

Although she was poor, Luz sent writing paper, envelopes, international reply coupons and reply-paid postcards to the children and parents. She transcribed each letter, believing this would reduce the likelihood of attracting the attention of wartime postal censors, and kept the original. After Luz passed away in 1971, the original letters were discovered by her nephew, who passed them along several years later to Dwork, who has written about children’s experiences in the Holocaust.

At the Kristallnacht commemoration, Dwork shared stories and correspondence of several families, including Wilhelm and Adele Halberstam. In 1939, their daughter Kathe and son-in-law Heinrich Hepner obtained visas for themselves and their three children and eventually made their way to Chile.

“Wilhelm and Adele decided not to emigrate,” Dwork said. “They stayed in Amsterdam with their son Albert. Thus began the parents’ long-distance relationship with their daughter and grandchildren, which depended upon letters.… They sought to weave a web of letters, to hold each other tightly and to assure each other that, notwithstanding the pressures of their radically changed circumstances, their relationships endured.”

Adele Halberstam wrote to her daughter: “I really live from letter to letter.”

As the occupation continued, the parents grew increasingly silent about developments at home, mentioning nothing of the expanding repression they were experiencing, including the imposition of the requirement to wear the yellow star.

“Out of consideration for you, I will not allow my pen to overflow with what fills my heart,” the mother wrote her daughter. “Why should you become as sad as I am?”

Regular mail service between Europe and Chile took longer and longer, then eventually ceased. The family came to rely on the Red Cross, which conveyed messages of 25 words or less. This limited means of communication continued after the Halberstams were deported from Amsterdam to the Dutch transit camp of Westerbork.

“The pattern of Adele’s messages remained consistent,” said Dwork. “Little discussion of the hardship, humiliation or fear and always an emphasis on family ties, love and longing.”

Eventually, some truths could not be withheld. An abrupt Red Cross message told the Hepners of Wilhelm Halberstam’s death by heart attack. Adele and Albert were deported to Auschwitz on Nov. 16, 1943. Adele was murdered on arrival. Albert survived until March 1944.

In another case, a son shared with Luz his fears for his parents’ survival, but did not convey that fear in the letter to his parents. In reply, the mother, writing from the Warsaw ghetto, wrote only of her yearning for her children and not of the horrors she was experiencing.

“Her last letter, written in November 1942, said not a word about the mass deportations to Treblinka that the Germans had just unleashed on the ghetto,” said Dwork.

Luz also helped Hanna Ruth Klopstock, another of the children in the care of OSE, correspond with her mother Frieda and brother Werner in Germany. When the girl had not heard from them in some time, she wrote to Luz expressing her fears.

“Every day I tell myself, today I must certainly get a letter from Mutti. And still nothing. I do not know what to think about this silence,” she wrote. “Maybe the letters have been lost. I hope so.”

The girl’s fears were well-founded, said Dwork. By the end of 1942, Werner had been sent to a forced labor camp in Germany, detailed to heavy agricultural work. The mother wrote to Luz: “I foresee nothing good and must hold myself together.” In the letter, Frieda Klopstock thanks Luz for everything she had done and makes a final request that Luz help and console Hanna Ruth when the inevitable occurs.

“Frieda was deported to Auschwitz six weeks later,” said Dwork. Luz and Hanna Ruth learned this news in a letter from Werner, who himself would follow his mother to the death camp a month later. Luz assumed the worst when a letter to Werner in the labor camp was returned with the address crossed out and the words “Zuruck” and “retour, parti” – return to sender, addressee departed – written on the envelope.

In a shocking twist though, Dwork added: “Remarkably, this is not the last sign of life from Werner.”

A postcard from Werner came some time later.

“Written in block letters,” Dwork said, “his message ran, ‘Dear Tante Elisabeth and dear Hanna Ruth, I inform you today that I am healthy and remain here for the future. Sadly, I have no news from you but I hope you are well. For today, very hearty greetings from Werner.’”

The message was just six lines, Dwork noted, not the full 10 permitted.

“What we know now is that the Nazis, too, recognized the importance of letters,” she said.

In his Nuremberg testimony, a Nazi official described the letter program of the Reich Security Main Office. Jews brought to extermination camps were forced, prior to being murdered, to write postcards that were then mailed at long intervals, in order to make it appear as though these senders were still alive. “And thus,” said Dwork, “letters that seemed a sign of life served as markers of death.”

Dwork’s remarks were preceded by a candlelight procession of survivors of the Holocaust. Cantor Yaacov Orzech chanted El Maleh Rachamim, a memorial prayer for the martyrs. Heather Deal, deputy mayor of Vancouver, read a proclamation from the city. Nina Krieger, executive director of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, introduced Deal and the keynote speaker. Beth Israel’s Rabbi Jonathan Infeld thanked Dwork and reflected on his own grandparents’ history of relying on letters from Europe to learn the fate of family left behind.

In his opening remarks to the program, Prof. Chris Friedrichs compared the situation of refugees today, who are fortunate, in many cases, to have access to technology that allows instant communication with loved ones left behind, while also acknowledging parallels across time.

“Nothing we say or do can bring back to life the six million Jews who perished, along with so many millions of others, during the darkest six years of the 20th century,” Friedrichs said. “But now, in the 21st century, the world is still full of desperate human beings longing for rescue or hope. There are things we can do to help bring families together, or to help build bridges of contact and connection. What we learn from the past must ever be our guide for the present and the future.”

Pat Johnson is a communications and development consultant for the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre.