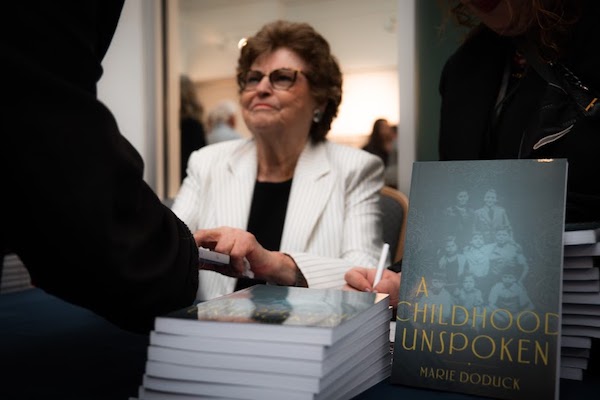

Marie Doduck speaks with a guest at the launch of her book A Childhood Unspoken on Jan. 22. (photo by Josias Tschanz)

“We survived.” These are the words that adult Marie Doduck would tell her childhood self, Mariette, who survived the Holocaust being moved from hiding place to hiding place over a period of five years.

Doduck was answering a question during a book launch laden with emotion – deeply sad as well as celebratory and with moments of laughter – Jan. 22 at a packed Rothstein Theatre. Her book, A Childhood Unspoken, was just released by the Azrieli Foundation’s Holocaust Survivor Memoirs Program.

In a conversation with Jody Spiegel, director of the memoirs program, Doduck spoke of how she is two people – the European Jewish child, Mariette Rozen, who never grew up, and the Canadian adult, Marie, who she had to create to suit her new surroundings after arriving in Vancouver with three orphaned siblings in 1947.

“Mariette will never grow old,” she said. “The child Mariette will always be the child inside and that’s what survivors live. We left the child that was in Europe, we created a wonderful life here in Canada, but when I speak and when I leave this room Mariette stays in this room and I become Marie again.”

Doduck explained her long hesitancy in sharing her story, not only because of the vulnerability it requires, but because the experiences of survivors like her had been dismissed and diminished in the past.

“As a child survivor,” she said, “we were told that we didn’t have a story.”

For decades after the end of the Holocaust, the term “survivor” was largely reserved for those who had been in concentration camps or subjected to forced labour. Child survivors who had been hidden or otherwise managed to escape capture and murder were deemed not to have suffered like older survivors.

This silent or quietly conveyed message was underscored by the way child survivors were treated after the war, even by well-intentioned adults like the families who fostered some of the 1,123 orphans, including Doduck, who came to Canada under the auspices of Canadian Jewish Congress from 1947 to 1949.

“We were from outer space,” she said of the reactions she and fellow child refugees received from Canadians. “We saw things that children should never have seen.”

Placed in homes with new families, with little or no assistance in addressing what they had experienced, many children did not do well.

“Of the 40 children who came to Vancouver, my brother Jacques and myself, I think, were the only two lucky children who stayed with the same family,” Doduck said. “My sister [Esther] didn’t stay with her first family, she became an au pair. Henri jumped from family to family.”

In some cases, said Doduck, the children were told they would die by the time they were 30 “because we were not normal in the Canadian eyes.”

Doduck wrote the book with Dr. Lauren Faulkner Rossi, assistant professor of history at Simon Fraser University. Speaking at the event and addressing Doduck directly, Faulkner Rossi acknowledged that the process was difficult.

“You would have to become the child Mariette many times,” she said, noting that Doduck was forced to plumb memories she has tried to forget. Faulkner Rossi said Doduck had to trust her, though Doduck’s “inclination is to trust no one – a crucial Holocaust childhood lesson that is never quite unlearned.”

“It’s a hard process for any child survivor to write their story,” Doduck said, not only because of the emotional toll but also because of the imperfections of childhood memories. “Did we hear it from adults? Did we live it? I wanted the truth.”

Doduck pressed Faulkner Rossi wherever possible to substantiate her recollections with historical evidence. During the process, Doduck recalled things she thought had been lost. “Sometimes one memory triggers another that you thought you had forgotten,” she said.

Doduck is a founding member of the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, through which she has shared her history with tens of thousands of students and others. She is also a philanthropist and community leader, volunteering and leading events, including co-chairing, with fellow VHEC co-founder Dr. Robert Krell, the 2019 conference of the World Federation of Jewish Child Survivors of the Holocaust and Descendants, in Vancouver.

Before Doduck’s presentation, VHEC executive director Nina Krieger described Doduck as “a force … a formidable and sought-after champion for many community organizations. She is also a mentor and a friend to so many, including me, and has inspired more than a generation of community leaders, especially young women, with her vision, passion, tenacity and work ethic, not to mention good humour and grace.”

The book launch event was presented by the VHEC and the Azrieli Foundation. Doduck’s daughters Cathy Golden and Bernice Carmeli read from the book. Arielle Berger, managing editor of the Azrieli Foundation, noted that, since 2005, the foundation has published more than 150 memoirs of Canadian survivors of the Holocaust. The foundation provides the books for free to schools and universities and also provides teaching resources and training to educators. This was the first in-person book launch since the pandemic.

The full theatre was still during an emotional moment when Doduck addressed her family in the front rows.

“I don’t say it often and I want to say it publicly to my children, my family sitting here, thank you for accepting who I am,” said Doduck, now a great-grandmother, before acknowledging the lack of experience with which she approached parenting. “When I was blessed with my children, my husband had to teach me how to go to the library and get a book,” she said. “I never knew a story to tell the kids.”

As a child, she said, Mariette was never hugged, never put to bed, was never kissed, never had a toy and never had a bedtime story.

“My first toy, I was 36 years old, I was the guest speaker in Winnipeg at a fundraiser,” she said, “and they gave me my first doll. I still have it. The only doll I ever had in my whole life.”

As a founding member of the local group of child survivors who meet regularly, Doduck tried to explain the uniqueness of child survivors to their own children.

“We all passed something to them that we didn’t realize we were doing, a burden that we gave to our children, our firstborn,” she said. “I apologize to all the firstborn. We didn’t mean to put a burden on you.”

She takes pride and sees a sense of progress in the different ways her three daughters have viewed her.

“My middle daughter, Bernice, always accepted me. That’s the way mom is,” she said. “That’s the middle child of all the survivors’ children. And my youngest daughter, Cheryl, may she rest in peace, only thought of me as a Canadian. So, I progressed. I fulfilled my duty in becoming Marie, the Canadian.”