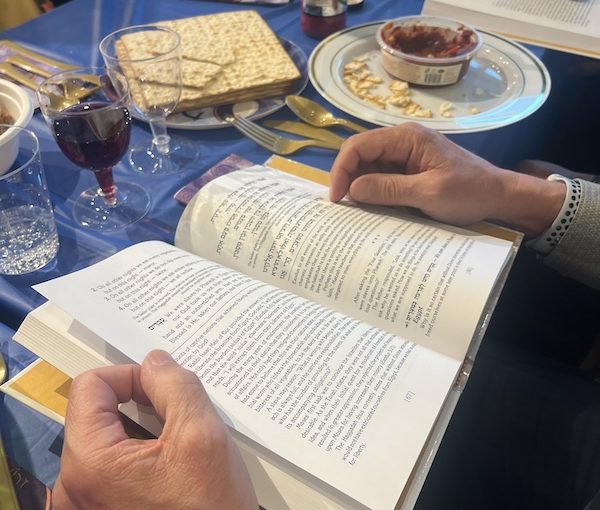

Scribe Mordechai Pinchas concluded Kolot Mayim Reform Temple’s 2024/25 Kvell at the Well series with the talk Torah Tales: Adventures in Scribal Art. (photo from Mordechai Pinchas)

On April 6, Mordechai Pinchas spoke about his experiences as a Jewish scribe (sofer, in Hebrew) in the final webinar of the 2024/25 Kvell at the Well series. Titled Torah Tales: Adventures in Scribal Art, the event was organized by Victoria’s Kolot Mayim Reform Temple.

Based in London, Pinchas, who is known academically as Marc Michaels, has been writing Torah scrolls, Megillat Esther, ketubot and the scrolls inside mezuzot and tefillin for more 30 years. He is a Cambridge scholar, earning a PhD in Jewish manuscripts from University of Cambridge’s faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern studies.

A Jewish scribe writes and restores holy works using quills, parchment and special inks, all the while following a strict set of rules, explained Pinchas. Indeed, there are many, many rules, which Pinchas came back to through the course of the talk.

The scribal art, he said, goes far beyond calligraphy and requires a detailed knowledge of Jewish law and a relatively high level of religious observance.

Pinchas provided a recipe for the special ink a scribe might use, which includes gum arabic, gallnuts (from oak trees), iron sulfate and water. The gallnuts are crushed to form tannic acid, mixed with the other ingredients and cooked on an open flame until a residue is left. The larger lumps of gallnuts are strained out and the mixture is left for six months to turn black and be used as ink.

For quills, Pinchas believes that a swan’s quill is too soft and a goose quill too hard and prefers a turkey quill. “As Goldilocks would say, it is just right,” he said.

Quills, Pinchas warned, must be adjusted in such a way to limit the risk of a scribe sneezing because, if that happens on parchment, it is impossible to remove. Scribes shifted to quills on the move to Europe, he said. Beforehand, they used reeds – which were used to write the Dead Sea Scrolls.

“We switched to quills because that’s what the Christians were using and they were getting a much finer, nicer point on their calligraphy,” he said.

A large part of a scribe’s job is repairing scrolls. Returning again to the rules, he said, “It only takes one letter to be wrong, and that means maybe the ink has come off or it’s broken or whatever, for the whole scroll to be pasul (invalid).”

If a scroll is deemed pasul, Pinchas told the audience, then it must be placed in the ark with an indicator to show it’s invalid, such as arranging its belt outside of its mantel. Jewish law states that it must be repaired within 30 days, but, he said, it may take much longer.

Among the Torah scroll repair horrors presented by Pinchas were gauze that joined seams together, stains from tape that had to be scraped out, and a patch that was sewn onto the scroll.

Typical repairs, he said, are not so extreme and mostly involve fading and broken letters, which require much overwriting. On occasion, whole columns no longer exist, having been completely rubbed away by time. Sometimes, members of a congregation might mark the scrolls with a pencil or ballpoint pen. In one slide Pinchas displayed, someone had drawn a flower onto the scroll.

In his career, Pinchas has also encountered incorrect spellings, deletions and Hebrew characters that were mistakenly joined together. Missing words, mixed-up letters and omitted characters from various Torah scrolls were shown to the Zoom crowd as well.

“And then you get wear and tear, dirt, holes, rips and things like that. You have to be very careful. You can patch a Torah, but you’re not allowed to do half patches,” he said.

What’s more, accidents can happen, especially when lifting the Torah during times when one side is much heavier than the other, ie., at the start and at the end of the yearly reading cycle. In one example, a Torah was torn through columns, thus the columns had to be removed and rewritten in the style of the original scribe.

Perhaps topping the list of Torah misadventures is the case Pinchas came across of a young person studying for her bat mitzvah and the family dog chewed through a section of the Torah.

“It was literally the best excuse for not learning a bat mitzvah portion – the dog ate my portion,” Pinchas joked.

“I had to do an emergency fix because there wasn’t enough time. I repaired it in the style of the original scroll, but only part of it, which you’re not normally supposed to do except in the case of an emergency – and this was a massive emergency. Because the parchment was much older than the shiny new parchment, I coated it with Yorkshire Tea. And it worked.”

A prolific author, designer and presenter, Pinchas designed the prayer book for the Movement for Reform Judaism and has written numerous books and articles on scrolls, the Bible and art; he wrote the children’s book The Dot on the Ot. Pinchas is currently working with Kolot Mayim to restore a Torah scroll.

Sam Margolis has written for the Globe and Mail, the National Post, UPI and MSNBC.